Summary

Early reperfusion therapy is a life-saving treatment for patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Primary PCI is the preferred method of reperfusion. However, the advantages of the invasive approach over fibrinolytic therapy may be reduced by late initiation of mechanical reperfusion due to logistical problems related to transportation delay to a hospital with a 24/7 invasive service. To overcome this limitation, regional programmes for coordination of the treatment of acute coronary syndromes are being introduced based on the cooperation of a PCI-capable hospital (hub) with ambulances and non-PCI-capable hospitals (spokes). With appropriate planning, only in a small minority of patients the anticipated delay to primay PCI will be so long to require pre- or in-hospital fibrinolytic therapy as a bridge to invasive therapy. PCI technique, as well as adjunctive pharmacotherapy in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction treatment, differ from standard PCI for stable angina due to the need for rapid intervention on thrombus containing lesions, which increases the risk of complications including distal embolisation or no-reflow. Modern aggressive antiplatelet therapyand new stent designs have improved the immediate and long-term results of primary PCI.

Networking of acute myocardial infarction treatment

The annual incidence of hospital admission for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) varies between 44-142/100,000 individuals per year [11. Widimsky P, Wijns W, Fajadet J, de Belder M, Knot J, Aaberge L, Andrikopoulos G, Baz JA, Betriu A, Claeys M, Danchin N, Djambazov S, Erne P, Hartikainen J, Huber K, Kala P, Klinceva M, Kristensen SD, Ludman P, Ferre JM, Merkely B, Milicic D, Morais J, Noc M, Opolski G, Ostojic M, Radovanovic D, De Servi S, Stenestrand U, Studencan M, Tubaro M, Vasiljevic Z, Weidinger F, Witkowski A, Zeymer U. Reperfusion therapy for ST elevation acute myocardial infarction in Europe: description of the current situation in 30 countries. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:943-957. ]. Reperfusion therapy is the most effective method of STEMI treatment. Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and thrombolysis represent the main strategies of reperfusion. The relative use of these two strategies is different across European countries. Importantly, in countries using mainly thrombolysis as a reperfusion strategy, the overall rate of reperfusion therapy in STEMI patients is lower than in countries with a dominance of primary PCI [11. Widimsky P, Wijns W, Fajadet J, de Belder M, Knot J, Aaberge L, Andrikopoulos G, Baz JA, Betriu A, Claeys M, Danchin N, Djambazov S, Erne P, Hartikainen J, Huber K, Kala P, Klinceva M, Kristensen SD, Ludman P, Ferre JM, Merkely B, Milicic D, Morais J, Noc M, Opolski G, Ostojic M, Radovanovic D, De Servi S, Stenestrand U, Studencan M, Tubaro M, Vasiljevic Z, Weidinger F, Witkowski A, Zeymer U. Reperfusion therapy for ST elevation acute myocardial infarction in Europe: description of the current situation in 30 countries. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:943-957. ]. A major increase in primary PCI utilization was observed in Europe during the last years. According to registry data from years 2010/2011 most countries has primary PCI rate around 400-600 procedures per million inhabitants (with the lowest number of 23 and highest number of 884 PCIs) [22. Kristensen SD, Laut KG, Fajadet J, Kaifoszova Z, Kala P, Di Mario C, Wijns W, Clemmensen P, Agladze V, Antoniades L, Alhabib KF, de Boer MJ, Claeys MJ, Deleanu D, Dudek D, Erglis A, Gilard M, Goktekin O, Guagliumi G, Gudnason T, Hansen KW, Huber K, James S, Janota T, Jennings S, Kajander O, Kanakakis J, Karamfiloff KK, Kedev S, Kornowski R, Ludman PF, Merkely B, Milicic D, Najafov R, Nicolini FA, Noc M, Ostojic M, Pereira H, Radovanovic D, Sabate M, Sobhy M, Sokolov M, Studencan M, Terzic I, Wahler S, Widimsky P. Reperfusion therapy for ST elevation acute myocardial infarction 2010/2011: current status in 37 ESC countries. Eur Heart J. 2014. ] - Figure 1.

According to the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Guidelines for STEMI treatment, primary PCI is the preferred method of reperfusion, but only when it is performed in a timely fashion by an experienced team [33. Steg PG, James SK, Atar D, Badano LP, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, Borger MA, Di Mario C, Dickstein K, Ducrocq G, Fernandez-Aviles F, Gershlick AH, Giannuzzi P, Halvorsen S, Huber K, Juni P, Kastrati A, Knuuti J, Lenzen MJ, Mahaffey KW, Valgimigli M, van ’t Hof A, Widimsky P, Zahger D. ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2569-2619. , 44. Wijns W, Kolh P, Danchin N, Di Mario C, Falk V, Folliguet T, Garg S, Huber K, James S, Knuuti J, Lopez-Sendon J, Marco J, Menicanti L, Ostojic M, Piepoli MF, Pirlet C, Pomar JL, Reifart N, Ribichini FL, Schalij MJ, Sergeant P, Serruys PW, Silber S, Sousa UM, Taggart D, Vahanian A, Auricchio A, Bax J, Ceconi C, Dean V, Filippatos G, Funck-Brentano C, Hobbs R, Kearney P, McDonagh T, Popescu BA, Reiner Z, Sechtem U, Sirnes PA, Tendera M, Vardas PE, Widimsky P, Kolh P, Alfieri O, Dunning J, Elia S, Kappetein P, Lockowandt U, Sarris G, Vouhe P, Kearney P, von Segesser L, Agewall S, Aladashvili A, Alexopoulos D, Antunes MJ, Atalar E, Brutel de la Riviere A, Doganov A, Eha J, Fajadet J, Ferreira R, Garot J, Halcox J, Hasin Y, Janssens S, Kervinen K, Laufer G, Legrand V, Nashef SA, Neumann FJ, Niemela K, Nihoyannopoulos P, Noc M, Piek JJ, Pirk J, Rozenman Y, Sabate M, Starc R, Thielmann M, Wheatley DJ, Windecker S, Zembala M. Guidelines on myocardial revascularization: The Task Force on Myocardial Revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2501-2555. , 55. Kushner FG, Hand M, Smith SC, Jr., King SB, III, Anderson JL, Antman EM, Bailey SR, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, Casey DE, Jr., Green LA, Hochman JS, Jacobs AK, Krumholz HM, Morrison DA, Ornato JP, Pearle DL, Peterson ED, Sloan MA, Whitlow PL, Williams DO. 2009 focused updates: ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (updating the 2004 guideline and 2007 focused update) and ACC/AHA/SCAI guidelines on percutaneous coronary intervention (updating the 2005 guideline and 2007 focused update) a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:2205-2241. , 168168. Windecker S, Kolh P, Alfonso F, Collet JP, Cremer J, Falk V, Filippatos G, Hamm C, Head SJ, Juni P, Kappetein AP, Kastrati A, Knuuti J, Landmesser U, Laufer G, Neumann FJ, Richter DJ, Schauerte P, Sousa Uva M, Stefanini GG, Taggart DP, Torracca L, Valgimigli M, Wijns W, Witkowski A. 2014 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization: The Task Force on Myocardial Revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS)Developed with the special contribution of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI). Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2541-2619. , 211211. Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Bueno H, Caforio ALP, Crea F, Goudevenos JA, Halvorsen S, Hindricks G, Kastrati A, Lenzen MJ, Prescott E, Roffi M, Valgimigli M, Varenhorst C, Vranckx P, Widimský P; ESC Scientific Document Group 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2018;39:119-177. ]. Data from national registries show that the recommended time delay from first medical contact (FMC) to primary PCI procedure is difficult to achieve, mainly due to the presentation of a large number of patients with STEMI in centres without an on-site primary PCI service [168168. Windecker S, Kolh P, Alfonso F, Collet JP, Cremer J, Falk V, Filippatos G, Hamm C, Head SJ, Juni P, Kappetein AP, Kastrati A, Knuuti J, Landmesser U, Laufer G, Neumann FJ, Richter DJ, Schauerte P, Sousa Uva M, Stefanini GG, Taggart DP, Torracca L, Valgimigli M, Wijns W, Witkowski A. 2014 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization: The Task Force on Myocardial Revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS)Developed with the special contribution of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI). Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2541-2619. , 211211. Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Bueno H, Caforio ALP, Crea F, Goudevenos JA, Halvorsen S, Hindricks G, Kastrati A, Lenzen MJ, Prescott E, Roffi M, Valgimigli M, Varenhorst C, Vranckx P, Widimský P; ESC Scientific Document Group 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2018;39:119-177. ]. This is an important limitation of mechanical reperfusion (see also the paragraph on timing issues). To overcome this limitation, the concept of networking was born which, by optimising the organisation of STEMI care, allowed an increase in the number of patients receiving mechanical reperfusion within the recommended time window. Well organised regional networks usually cover an area of about 0.3 to 0.5 million inhabitants and consist of a PCI centre (hub), non-PCI hospitals (spokes) and the emergency medical systems. Networks covering larger populations also exist, especially when located in large metropolitan areas. In Europe, the average population for network is approximately 0.5 million inhabitants [88. Knot J, Widimsky P, Wijns W, Stenestrand U, Kristensen SD, van’t Hof AW, Weidinger F, Janzon M, Norgaard BL, Soerensen JT, van de Wetering H, Thygesen K, Bergsten PA, Digerfeldt C, Potgieter A, Tomer N, Fajadet J. How to set up an effective national primary angioplasty network: lessons learned from five European countries. EuroIntervention. 2009;5:299-309. ]. A smaller area provides a lower number of STEMI patients which decreases network effectiveness, whereas in larger areas transportation, catheterisation facilities and coronary care unit beds may be overloaded by the high number of patients. Typically, networks are centrally coordinated and have predefined transportation and treatment protocols which are important for reducing the time delay. Ideally, the coordinating centre should provide training programmes and quality control with evaluation of outcome via local audits compared with the general experience collected in national registries). These are important tools to improve the system. Only experienced, high-volume centres providing a 24/7 service should be part of a network because both operator volume and hospital volume influence primary PCI results [99. Srinivas VS, Hailpern SM, Koss E, Monrad ES, Alderman MH. Effect of physician volume on the relationship between hospital volume and mortality during primary angioplasty. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:574-579. , 1010. Kumbhani DJ, Cannon CP, Fonarow GC, Liang L, Askari AT, Peacock WF, Peterson ED, Bhatt DL. Association of hospital primary angioplasty volume in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction with quality and outcomes. JAMA. 2009;302:2207-2213. ]. This is very important for network planning in order to obtain optimal balance between the number of primary PCI centres and the number of inhabitants in the area of a particular network (number of STEMI) because both will influence the operator’s experience and time delay, which is important for treatment results.

Pre-hospital diagnosis of STEMI allows bypassing the emergency room and transferring the patients directly to the cath lab, which reduces the time to reperfusion [1111. Terkelsen CJ, Lassen JF, Norgaard BL, Gerdes JC, Poulsen SH, Bendix K, Ankersen JP, Gotzsche LB, Romer FK, Nielsen TT, Andersen HR. Reduction of treatment delay in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: impact of pre-hospital diagnosis and direct referral to primary percutanous coronary intervention. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:770-777. , 1212. Bang A, Grip L, Herlitz J, Kihlgren S, Karlsson T, Caidahl K, Hartford M. Lower mortality after prehospital recognition and treatment followed by fast tracking to coronary care compared with admittance via emergency department in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol. 2008;129:325-332. ]. Electrocardiogram (ECG) interpretation can be done by the ambulance staff or via transmission from the ambulance to the PCI hospital or a central coordinating centre. This last modality can be helpful when the ECG interpretation is difficult, especially in paramedic-based ambulance systems. In the many regions worldwide where ECG teletrasmission has been implemented, this system leads to a reduced time to mechanical reperfusion and facilitates the activation of cath lab staff, especially during off-duty hours [1313. Rokos IC, French WJ, Koenig WJ, Stratton SJ, Nighswonger B, Strunk B, Jewell J, Mahmud E, Dunford JV, Hokanson J, Smith SW, Baran KW, Swor R, Berman A, Wilson BH, Aluko AO, Gross BW, Rostykus PS, Salvucci A, Dev V, McNally B, Manoukian SV, King SB, III. Integration of pre-hospital electrocardiograms and ST-elevation myocardial infarction receiving center (SRC) networks: impact on Door-to-Balloon times across 10 independent regions. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2:339-346. , 1414. Rao A, Kardouh Y, Darda S, Desai D, Devireddy L, Lalonde T, Rosman H, David S. Impact of the prehospital ECG on door-to-balloon time in ST elevation myocardial infarction. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;75:174-178. ]. Regional protocols for STEMI networks differ within European countries according to specific local constraints [88. Knot J, Widimsky P, Wijns W, Stenestrand U, Kristensen SD, van’t Hof AW, Weidinger F, Janzon M, Norgaard BL, Soerensen JT, van de Wetering H, Thygesen K, Bergsten PA, Digerfeldt C, Potgieter A, Tomer N, Fajadet J. How to set up an effective national primary angioplasty network: lessons learned from five European countries. EuroIntervention. 2009;5:299-309. , 1515. Danchin N. Systems of care for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: impact of different models on clinical outcomes. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2:901-908. ]. In some of them, pre-hospital fibrinolysis was introduced as a bridge to mechanical reperfusion.

The STEMI networking concept was actively promoted by the European “Stent for Life” initiative (2008-2016), in which the main goal was to promote mechanical reperfusion in Europe by reducing the time delay to reperfusion and increasing the number of patients with STEMI undergoing mechanical reperfusion. During the last few years, many European countries have improved dramatically their rates of primary angioplasty implementing the plans advised by the “Stent for Life” group, inspired by the experience of the best-performing countries. The survey on reperfusion strategies promoted as part of the “Stent for Life” initiative has shown that most countries have reached the target penetration and a full supplement of EuroIntervention has been dedicated to an individual analysis of the situation in individual countries and regions. ( > Eurointervention Volume 8 Supplement P ). Currently the “Stent - Save a Life” programme is ongoing following the success of Stent for Life initiative. The primary intention of “Stent - Save a Life” is to extend this idea globally, according to the increasing needs, and to adapt it to the specific demands of the various regions of the world (www.stentsavealife.com).

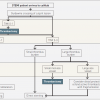

These principles have been adopted by the ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (MI) as well as the most recent ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. They recommend that the pre-hospital management of STEMI patients must be based on regional networks designed to deliver reperfusion therapy expeditiously and effectively, with efforts made to offer primary PCI to as many patients as possible (recommendation Class I; level of evidence B). Primary PCI-capable centres must deliver a 24/7 service and be able to start primary PCI as soon as possible but always within 60 min from the initial call (recommendation Class I; level of evidence B). It is recommended that the emergency medical system transfers STEMI patients to a PCI-capable centre, bypassing non-PCI centres (recommendation Class I; level of evidence C). Patients transferred to a PCI-capable centre for primary PCI should bypass the emergency department, coronary care unit/intensive cardiac care unit and be transferred directly to the cath lab (recommendation Class I; level of evidence B) [168168. Windecker S, Kolh P, Alfonso F, Collet JP, Cremer J, Falk V, Filippatos G, Hamm C, Head SJ, Juni P, Kappetein AP, Kastrati A, Knuuti J, Landmesser U, Laufer G, Neumann FJ, Richter DJ, Schauerte P, Sousa Uva M, Stefanini GG, Taggart DP, Torracca L, Valgimigli M, Wijns W, Witkowski A. 2014 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization: The Task Force on Myocardial Revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS)Developed with the special contribution of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI). Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2541-2619. , 211211. Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Bueno H, Caforio ALP, Crea F, Goudevenos JA, Halvorsen S, Hindricks G, Kastrati A, Lenzen MJ, Prescott E, Roffi M, Valgimigli M, Varenhorst C, Vranckx P, Widimský P; ESC Scientific Document Group 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2018;39:119-177. ]. ( Figure 2).

Timing issues

There are a number of factors that may influence progression of myocardial necrosis during MI: completeness of coronary occlusion, presence of collateral circulation, pre- and post-conditioning, individual myocardial oxygen demand. Despite the variability of these factors, duration of ischaemia remains the most important determinant of infarct size and myocardial damage. It is widely accepted and recommended by current ESC guidelines that reperfusion therapy is indicated in all STEMI patients with symptoms of ischemia <12 hours (recommendation Class I; level of evidence A). Also, a primary PCI strategy is indicated in the presence of ongoing symptoms suggestive of ischaemia, haemodynamic instability, or life-threatening arrhythmias.(recommendation Class I.; level of evidence C). A routine primary PCI strategy should be considered in patients presenting late (12–48 h) after symptom onset (recommendation Class IIa; level of evidence B). [211211. Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Bueno H, Caforio ALP, Crea F, Goudevenos JA, Halvorsen S, Hindricks G, Kastrati A, Lenzen MJ, Prescott E, Roffi M, Valgimigli M, Varenhorst C, Vranckx P, Widimský P; ESC Scientific Document Group 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2018;39:119-177. ]. Primary PCI, which is the preferred reperfusion therapy, should be started in specific timeframes. This might be difficult, due to logistical problems, when prolonged transfer to the centre with 24/7 invasive facilities is necessary.

TIME DELAYS IN MYOCARDIAL INFARCTION

When analysing the timing of events in STEMI treatment, several delay times can be determined. The moment when the patient meets the medical system for the first time is called first medical contact (FMC). The ischaemic time before FMC is called delay between symptoms onset and FMC and this is mainly a patient-related delay, with improvements possible only via education to recognise symptoms and timely call to a unified number for the emergency service. At the FMC time point the initial diagnosis should be established and any further time delay is related to the medical system. According to recent ESC STEMI Guidelines, the delay from FMC to STEMI diagnosis should be reduced to less than 10 min. STEMI diagnosis time is the time zero to guide appropriate therapy. Another important moment is the start of reperfusion therapy, traditionally defined by first balloon inflation or first thrombectomy catheter pass but now identified from the wire passage distal to the occluded segment. Door-to-needle time represents its equivalent when fibrinolytic therapy is given. These three time points (symptoms onset, STEMI diagnosis, first wire passage with primary PCI and needle time with fibrinolysis) are the most important time-points in the diagnosis and treatment process in STEMI patients. System-related delay times may be calculated from FMC to hospital admission, cath lab admission, sheath insertion etc, but the most important is the time from STEMI diagnosis to first wire crossing since thrombectomy of direct stent implantation are often used instead of balloon dilatation during PCI. For patients treated with fibrinolysis, the most important parameter is the time from STEMI diagnosis to fibrinolytic therapy administration. The above-mentioned time delays are also called door-to-balloon time and door-to-needle time. However, the “door” moment may not always be defined as “first door” (which equals FMC), but can be hospital door or cath lab door that gives a different time relation. Especially when analysing primary PCI compared to fibrinolysis, there is controversy that the clock for primary PCI starts at the time of FMC but that for fibrinolysis the clock starts ticking after arrival at the hospital, which does not include any transportation delay. That is why it is better to use the FMC and STEMI diagnosis time points for description of delay times. Details concerning delay times are described in Table 1. Additionally, for primary PCI, wire crossing time point equates to the moment of reperfusion, whereas needle time equates to lysis delivery but precedes effective reperfusion.

IMPORTANCE OF DELAY TO MECHANICAL REPERFUSION

The relationship between reperfusion treatment delay and mortality has been studied extensively, mainly in post hoc analyses based on observational data from randomised trials and registries. Early studies suggested that the time dependency of mechanical reperfusion exists but it is less pronounced than in fibrinolysis. Zijlstra et al demonstrated the relationship between time delay and mortality in fibrinolysis, but not in primary PCI-treated patients [1616. Zijlstra F, Patel A, Jones M, Grines CL, Ellis S, Garcia E, Grinfeld L, Gibbons RJ, Ribeiro EE, Ribichini F, Granger C, Akhras F, Weaver WD, Simes RJ. Clinical characteristics and outcome of patients with early (4 h) presentation treated by primary coronary angioplasty or thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2002;23:550-557. ]. Cannon et al found that mortality after primary PCI is not related to symptom onset-to-balloon time [1717. Cannon CP, Gibson CM, Lambrew CT, Shoultz DA, Levy D, French WJ, Gore JM, Weaver WD, Rogers WJ, Tiefenbrunn AJ. Relationship of symptom-onset-to-balloon time and door-to-balloon time with mortality in patients undergoing angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2000;283:2941-2947. ]. In a series of more than 1,300 patients Antoniucci et al showed a positive correlation between time to treatment and mortality in high-risk patients but not in low-risk patients [1818. Antoniucci D, Valenti R, Migliorini A, Moschi G, Trapani M, Buonamici P, Cerisano G, Bolognese L, Santoro GM. Relation of time to treatment and mortality in patients with acute myocardial infarction undergoing primary coronary angioplasty. Am J Cardiol. 2002;89:1248-1252. ]. Similarly, Brodie et al [1919. Brodie BR, Stuckey TD, Muncy DB, Hansen CJ, Wall TC, Pulsipher M, Gupta N. Importance of time-to-reperfusion in patients with acute myocardial infarction with and without cardiogenic shock treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Am Heart J. 2003;145:708-715. ] demonstrated a significant relationship between time to treatment and mortality only in high-risk patients with cardiogenic shock. However, De Luca et al [2020. De Luca G, Suryapranata H, Ottervanger JP, Antman EM. Time delay to treatment and mortality in primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction: every minute of delay counts. Circulation. 2004;109:1223-1225. ], analysing long-term outcome, found that there was a definite relationship between time delay to PCI treatment and 1-year mortality also in a general primary PCI population. Each 30 minutes of delay was associated with a relative risk increase of 7.5% at 1-year follow-up [2020. De Luca G, Suryapranata H, Ottervanger JP, Antman EM. Time delay to treatment and mortality in primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction: every minute of delay counts. Circulation. 2004;109:1223-1225. ]. Similarly, Nallamothu et al [2121. Nallamothu B, Fox KA, Kennelly BM, Van de Werf F, Gore JM, Steg PG, Granger CB, Dabbous OH, Kline-Rogers E, Eagle KA. Relationship of treatment delays and mortality in patients undergoing fibrinolysis and primary percutaneous coronary intervention. The Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events. Heart. 2007;93:1552-1555. ], based on GRACE registry data, showed that longer treatment delays were associated with higher 6-month mortality in both fibrinolysis and primary PCI patients. For primary PCI patients, 6-month mortality increased by 0.18% per 10 minutes delay in door-to-balloon time between 90 and 150 minutes [2121. Nallamothu B, Fox KA, Kennelly BM, Van de Werf F, Gore JM, Steg PG, Granger CB, Dabbous OH, Kline-Rogers E, Eagle KA. Relationship of treatment delays and mortality in patients undergoing fibrinolysis and primary percutaneous coronary intervention. The Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events. Heart. 2007;93:1552-1555. ]. Observational studies correlating treatment delay and mortality after primary PCI should be interpreted with caution. Patients who present early are more likely to be at high risk than late presenters [2222. Aquaro GD, Pingitore A, Strata E, Di Bella G, Palmieri C, Rovai D, Petronio AS, L’Abbate A, Lombardi M. Relation of pain-to-balloon time and myocardial infarct size in patients transferred for primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100:28-34. ]. Therefore, the apparent similarity of outcome irrespective of time delay may only be the consequence of a worse a priori outcome of high-risk individuals treated early and the better outcome of lower-risk patients treated later. Gersh et al has suggested that, in patients presenting late from symptoms onset, time delay to PCI has a minimal impact on mortality (plateau phase) [2323. Gersh BJ, Stone GW, White HD, Holmes DR, Jr. Pharmacological facilitation of primary percutaneous coronary intervention for acute myocardial infarction: is the slope of the curve the shape of the future?. JAMA. 2005;293:979-986. ]. The benefit of time delay reduction may not be similar in all patients but related to risk profile and time of presentation. For ethical reasons, it is impossible to assess properly the role of reducing delay to mechanical reperfusion in a randomised fashion. However, based on current evidence, it is recommended to make as much of an effort as possible to reduce delays to mechanical reperfusion.

PCI-RELATED DELAY

Primary PCI is the preferred form of reperfusion treatment for patients with STEMI [33. Steg PG, James SK, Atar D, Badano LP, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, Borger MA, Di Mario C, Dickstein K, Ducrocq G, Fernandez-Aviles F, Gershlick AH, Giannuzzi P, Halvorsen S, Huber K, Juni P, Kastrati A, Knuuti J, Lenzen MJ, Mahaffey KW, Valgimigli M, van ’t Hof A, Widimsky P, Zahger D. ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2569-2619. , 44. Wijns W, Kolh P, Danchin N, Di Mario C, Falk V, Folliguet T, Garg S, Huber K, James S, Knuuti J, Lopez-Sendon J, Marco J, Menicanti L, Ostojic M, Piepoli MF, Pirlet C, Pomar JL, Reifart N, Ribichini FL, Schalij MJ, Sergeant P, Serruys PW, Silber S, Sousa UM, Taggart D, Vahanian A, Auricchio A, Bax J, Ceconi C, Dean V, Filippatos G, Funck-Brentano C, Hobbs R, Kearney P, McDonagh T, Popescu BA, Reiner Z, Sechtem U, Sirnes PA, Tendera M, Vardas PE, Widimsky P, Kolh P, Alfieri O, Dunning J, Elia S, Kappetein P, Lockowandt U, Sarris G, Vouhe P, Kearney P, von Segesser L, Agewall S, Aladashvili A, Alexopoulos D, Antunes MJ, Atalar E, Brutel de la Riviere A, Doganov A, Eha J, Fajadet J, Ferreira R, Garot J, Halcox J, Hasin Y, Janssens S, Kervinen K, Laufer G, Legrand V, Nashef SA, Neumann FJ, Niemela K, Nihoyannopoulos P, Noc M, Piek JJ, Pirk J, Rozenman Y, Sabate M, Starc R, Thielmann M, Wheatley DJ, Windecker S, Zembala M. Guidelines on myocardial revascularization: The Task Force on Myocardial Revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2501-2555. , 211211. Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Bueno H, Caforio ALP, Crea F, Goudevenos JA, Halvorsen S, Hindricks G, Kastrati A, Lenzen MJ, Prescott E, Roffi M, Valgimigli M, Varenhorst C, Vranckx P, Widimský P; ESC Scientific Document Group 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2018;39:119-177. ]. However, the advantages of an invasive approach over fibrinolytic therapy may be reduced by the additional delay to initiation of mechanical reperfusion due to logistical problems. PCI-related delay is the additional delay necessary to perform primary PCI instead of fibrinolysis administration. This is the theoretical difference between the time of FMC to wire crossing minus the time from FMC to the start of fibrinolytic therapy. The maximum acceptable PCI-related delay, beyond which the benefit of primary PCI is completely counterbalanced by the harmful effect of reperfusion initiation delay, has been analysed in many studies. The majority of them were trial-based but not individual patient-data-based meta-analyses. Kent et al showed that a delay of 50 minutes as threshold yielded equivalent reductions in mortality for both primary PCI and thrombolysis [2424. Kent DM, Lau J, Selker HP. Balancing the benefits of primary angioplasty against the benefits of thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: the importance of timing. Eff Clin Pract. 2001;4:214-220. ]. In the analysis of Nallamothu et al [2525. Nallamothu BK, Bates ER. Percutaneous coronary intervention versus fibrinolytic therapy in acute myocardial infarction: is timing (almost) everything?. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:824-826. ], the primary PCI mortality benefit was lost if PCI-related delay exceeded 88 minutes. Pinto et al [2626. Pinto DS, Kirtane AJ, Nallamothu BK, Murphy SA, Cohen DJ, Laham RJ, Cutlip DE, Bates ER, Frederick PD, Miller DP, Carrozza JP, Jr., Antman EM, Cannon CP, Gibson CM. Hospital delays in reperfusion for ST-elevation myocardial infarction: implications when selecting a reperfusion strategy. Circulation. 2006;114:2019-2025. ] showed in a combined analysis of the NRMI-2, 3 and 4 that the maximum acceptable PCI-related delay was much longer, i.e, 114 minutes, and varied considerably depending on various factors like duration of symptoms, age and infarction location. This suggests an individualised rather than a uniform approach for selecting an optimal reperfusion strategy. In the paper by Betriu et al [2727. Betriu A, Masotti M. Comparison of mortality rates in acute myocardial infarction treated by percutaneous coronary intervention versus fibrinolysis. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:100-101. ], regression analysis showed that the mortality rate for PCI remained the same as that for fibrinolysis when the PCI-related time delay reached 110 minutes. De Luca et al [2828. De Luca G, Cassetti E, Marino P. Percutaneous coronary intervention-related time delay, patient’s risk profile, and survival benefits of primary angioplasty vs lytic therapy in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Am J Emerg Med. 2009;27:712-719. ] found equipoise between primary angioplasty and fibrinolysis at 180 minutes. Only one individual patient data meta-analysis by Boersma et al [2929. Boersma E. Does time matter?. A pooled analysis of randomized clinical trials comparing primary percutaneous coronary intervention and in-hospital fibrinolysis in acute myocardial infarction patients. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:779-788. ] demonstrated that invasive treatment remains superior over fibrinolysis even for a PCI-related delay of 80-120 minutes (the analysis included only patients with a time delay <120 minutes). In the STREAM Study on STEMI patients presenting early (up to 3 hours from symptoms onset) with an anticipated delay to PCI longer than 60 minutes, despite a relative delay to PCI of 78 minutes early fibrinolysis was not associated with reduction of ischaemic events. Moreover, an increased rate of bleeding was found in patients randomised to fibrinolysis [3030. Armstrong PW, Gershlick AH, Goldstein P, Wilcox R, Danays T, Lambert Y, Sulimov V, Rosell OF, Ostojic M, Welsh RC, Carvalho AC, Nanas J, Arntz HR, Halvorsen S, Huber K, Grajek S, Fresco C, Bluhmki E, Regelin A, Vandenberghe K, Bogaerts K, Van de Werf F. Fibrinolysis or primary PCI in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1379-1387. ].

According to available data it is difficult to define the time limit to prefer primary PCI over fibrinolysis precisely. In current ESC STEMI guidelines the absolute time from STEMI diagnosis to PCI-mediated reperfusion rather than a relative PCI-related delay over fibrinolysis has been chosen. It is recommended that an expected maximum delay of 120 min from STEMI diagnosis to primary PCI (wire crossing), should be used in selecting a primary PCI strategy over fibrynolysis. However, as a target for quality assessment, primary PCI should be performed within 90 min after FMC in transferred patients and ≤60 min in patients presenting directly in a PCI-capable hospital For patients presenting in non-PCI centers the delay between arrival to this hospital and discharge (start of transfer with ambulance to the PCI center) should be ≤30 min. Importantly, it is recommended to record and audit delay times and work to achieve and maintain quality targets [211211. Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Bueno H, Caforio ALP, Crea F, Goudevenos JA, Halvorsen S, Hindricks G, Kastrati A, Lenzen MJ, Prescott E, Roffi M, Valgimigli M, Varenhorst C, Vranckx P, Widimský P; ESC Scientific Document Group 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2018;39:119-177. ]. The organisation of STEMI treatment strategy based on anticipated delay to reperfusion is shown in Figure 3.

TIMING OF ANGIOGRAPHY AND PCI AFTER LYSIS

Routine angiography/PCI

Despite the progress made hitherto, challenges remain. The diffusion of STEMI networks has reduced drastically the number of patients not treatable with primary PCI. The remaining limited patient groups living too far from 24/7 hubs to receive primary PCI in time, however, are disadvantaged by not receiving the most efficacious reperfusion treatment. To this can be added the additional disadvantage that the evidence gathered from the seminal studies of the last decade is not applied routinely or in a timely fashion, and that no new major studies have been conducted or new strategies designed recently. Research into new drugs for this acute indication have also come to a stop in recent years. .

In clinical trials from the 1980s and 1990s, immediate PCI for STEMI following full-dose fibrinolysis (so-called facilitated PCI) was found to be associated with low angiographic efficacy and worse clinical outcome [3131. Topol EJ, Califf RM, George BS, Kereiakes DJ, Abbottsmith CW, Candela RJ, Lee KL, Pitt B, Stack RS, O’Neill WW. A randomized trial of immediate versus delayed elective angioplasty after intravenous tissue plasminogen activator in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:581-588. , 3232. O’Neill WW, Weintraub R, Grines CL, Meany TB, Brodie BR, Friedman HZ, Ramos RG, Gangadharan V, Levin RN, Choksi N, . A prospective, placebo-controlled, randomized trial of intravenous streptokinase and angioplasty versus lone angioplasty therapy of acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1992;86:1710-1717. ]. This might depend on the lack of antiplatelet therapy and the increased prothrombotic state after fibrinolysis [3333. Owen J, Friedman KD, Grossman BA, Wilkins C, Berke AD, Powers ER. Thrombolytic therapy with tissue plasminogen activator or streptokinase induces transient thrombin activity. Blood. 1988;72:616-620. , 3434. Fitzgerald DJ, Catella F, Roy L, FitzGerald GA. Marked platelet activation in vivo after intravenous streptokinase in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1988;77:142-150. ]. In the ASSENT-4 PCI study [3535. Primary versus tenecteplase-facilitated percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction (ASSENT-4 PCI): randomised trial. Lancet. 2006;367:569-578. ], a strategy of immediate PCI after fibrinolysis was found to be harmful but many PCI procedures were performed at the time of maximal platelet activation after tenecteplase in patients receiving a suboptimal antiplatelet therapy with only aspirin. Several studies were conducted to assess the role and optimal moment of routine angiography/PCI after fibrinolysis. Some of those trials included an additional transfer to a PCI centre from non-PCI centres after fibrinolysis administration. This strategy represents the so-called pharmaco-invasive approach when fibrinolysis is administered as the initial reperfusion due to the anticipated delay to primary PCI caused by transfer logistics. In the SIAM III trial, a strategy of early angiography and immediate stenting (3.5 ± 2.3 hours after fibrinolysis) was associated with a significant reduction of the combined endpoints of death, re-infarction, target lesion revascularisation (TLR) and other ischaemic events after 30 days and 6 months [3636. Scheller B, Hennen B, Hammer B, Walle J, Hofer C, Hilpert V, Winter H, Nickenig G, Bohm M. Beneficial effects of immediate stenting after thrombolysis in acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:634-641. ]. Similarly, in the GRACIA-1 study, after the mean time from fibrinolytic agent infusion to coronary angiography of 16.7 ± 5.6 hours, the early angiography/PCI approach was associated with significant risk reduction of the combined endpoint of death, non-fatal re-infarction and revascularisation at 1 year in comparison to the conservative group [3737. Fernandez-Aviles F, Alonso JJ, Castro-Beiras A, Vazquez N, Blanco J, onso-Briales J, Lopez-Mesa J, Fernandez-Vazquez F, Calvo I, Martinez-Elbal L, San Roman JA, Ramos B. Routine invasive strategy within 24 hours of thrombolysis versus ischaemia-guided conservative approach for acute myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation (GRACIA-1): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:1045-1053. ]. In the CARESS in AMI trial, transfer of high-risk STEMI patients for early routine PCI soon after the administration of abciximab and half-dose reteplase was shown to reduce the risk of recurrent ischaemia and all ischaemic complications at 30 days in comparison to conservatively treated patients with ischaemia-guided PCI (rescue PCI). The median time from fibrinolysis initiation to angiography in immediate PCI group was 135 minutes [3838. Di Mario C, Dudek D, Piscione F, Mielecki W, Savonitto S, Murena E, Dimopoulos K, Manari A, Gaspardone A, Ochala A, Zmudka K, Bolognese L, Steg PG, Flather M. Immediate angioplasty versus standard therapy with rescue angioplasty after thrombolysis in the Combined Abciximab REteplase Stent Study in Acute Myocardial Infarction (CARESS-in-AMI): an open, prospective, randomised, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2008;371:559-568. ]. Similarly, in the TRANSFER-AMI trial [3939. Cantor WJ, Fitchett D, Borgundvaag B, Ducas J, Heffernan M, Cohen EA, Morrison LJ, Langer A, Dzavik V, Mehta SR, Lazzam C, Schwartz B, Casanova A, Goodman SG. Routine early angioplasty after fibrinolysis for acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2705-2718. ], enrolling high-risk STEMI patients, the pharmaco-invasive strategy (immediate transfer for PCI within 6 hours of fibrinolysis) was associated with better clinical outcome than standard treatment after fibrinolysis with tenecteplase (rescue PCI for failed reperfusion, with elective PCI encouraged for successfully reperfused patients after 24 hours). The median time from fibrinolysis initiation to angiography was 3 hours. What is important is that all patients received aspirin, heparin, a loading dose of clopidogrel, and, in 73% of patients undergoing immediate PCI, glycoprotein (GP) IIb-IIIa inhibitors [3939. Cantor WJ, Fitchett D, Borgundvaag B, Ducas J, Heffernan M, Cohen EA, Morrison LJ, Langer A, Dzavik V, Mehta SR, Lazzam C, Schwartz B, Casanova A, Goodman SG. Routine early angioplasty after fibrinolysis for acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2705-2718. ]. In all the above-mentioned studies, no increase in bleeding events was observed. The GRACIA-2 authors report that early routine post-fibrinolysis PCI performed at 3–12 h after initiation of lytic therapy with the mean time to PCI of 6 h (median 4.6 hours) is safe, and results for myocardial perfusion better than primary angioplasty [4040. Fernandez-Aviles F, Alonso JJ, Pena G, Blanco J, onso-Briales J, Lopez-Mesa J, Fernandez-Vazquez F, Moreu J, Hernandez RA, Castro-Beiras A, Gabriel R, Gibson CM, Sanchez PL. Primary angioplasty vs. early routine post-fibrinolysis angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation: the GRACIA-2 non-inferiority, randomized, controlled trial. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:949-960. ]. The safety of PCI early after fibrinolysis was also confirmed in NORDISTEMI, with a high utilisation of a radial approach explaining the very low incidence of access site complications [4141. Bohmer E, Hoffmann P, Abdelnoor M, Arnesen H, Halvorsen S. Efficacy and safety of immediate angioplasty versus ischemia-guided management after thrombolysis in acute myocardial infarction in areas with very long transfer distances results of the NORDISTEMI (NORwegian study on DIstrict treatment of ST-elevation myocardial infarction). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:102-110. ]. In the meta-analysis of 7 clinical trials [3535. Primary versus tenecteplase-facilitated percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction (ASSENT-4 PCI): randomised trial. Lancet. 2006;367:569-578. , 3636. Scheller B, Hennen B, Hammer B, Walle J, Hofer C, Hilpert V, Winter H, Nickenig G, Bohm M. Beneficial effects of immediate stenting after thrombolysis in acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:634-641. , 3737. Fernandez-Aviles F, Alonso JJ, Castro-Beiras A, Vazquez N, Blanco J, onso-Briales J, Lopez-Mesa J, Fernandez-Vazquez F, Calvo I, Martinez-Elbal L, San Roman JA, Ramos B. Routine invasive strategy within 24 hours of thrombolysis versus ischaemia-guided conservative approach for acute myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation (GRACIA-1): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:1045-1053. , 3838. Di Mario C, Dudek D, Piscione F, Mielecki W, Savonitto S, Murena E, Dimopoulos K, Manari A, Gaspardone A, Ochala A, Zmudka K, Bolognese L, Steg PG, Flather M. Immediate angioplasty versus standard therapy with rescue angioplasty after thrombolysis in the Combined Abciximab REteplase Stent Study in Acute Myocardial Infarction (CARESS-in-AMI): an open, prospective, randomised, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2008;371:559-568. , 3939. Cantor WJ, Fitchett D, Borgundvaag B, Ducas J, Heffernan M, Cohen EA, Morrison LJ, Langer A, Dzavik V, Mehta SR, Lazzam C, Schwartz B, Casanova A, Goodman SG. Routine early angioplasty after fibrinolysis for acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2705-2718. , 4040. Fernandez-Aviles F, Alonso JJ, Pena G, Blanco J, onso-Briales J, Lopez-Mesa J, Fernandez-Vazquez F, Moreu J, Hernandez RA, Castro-Beiras A, Gabriel R, Gibson CM, Sanchez PL. Primary angioplasty vs. early routine post-fibrinolysis angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation: the GRACIA-2 non-inferiority, randomized, controlled trial. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:949-960. , 4242. Armstrong PW. A comparison of pharmacologic therapy with/without timely coronary intervention vs. primary percutaneous intervention early after ST-elevation myocardial infarction: the WEST (Which Early ST-elevation myocardial infarction Therapy) study. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1530-1538. ] comparing early routine PCI after fibrinolysis vs. standard therapy, lower rates of re-infarction, death and re-infarction at 30 days and 6-12 months and recurrent ischaemia at 30 days were found after early PCI. There was no difference in terms of stroke and major bleedings between the groups [4343. Borgia F, Goodman SG, Halvorsen S, Cantor WJ, Piscione F, Le May MR, Fernandez-Aviles F, Sanchez PL, Dimopoulos K, Scheller B, Armstrong PW, Di Mario C. Early routine percutaneous coronary intervention after fibrinolysis vs. standard therapy in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2156-2169. ].

After fibrinolysis all patients should be immediately transferred to a PCI-capable center (recommendation Class I; level of evidence A) and routine coronary angiography and, if applicable, PCI are recommended between 2 and 24 h after successful fibrinolysis (recommendation Class I; level of evidence A). [211211. Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Bueno H, Caforio ALP, Crea F, Goudevenos JA, Halvorsen S, Hindricks G, Kastrati A, Lenzen MJ, Prescott E, Roffi M, Valgimigli M, Varenhorst C, Vranckx P, Widimský P; ESC Scientific Document Group 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2018;39:119-177. ]. It seems to be indisputable that while promptly delivering fibrinolysis the operator should already be planning an immediate transfer to a centre with invasive facilities instead of waiting for fibrinolysis. The absence of negative effects of early angioplasty post-fibrinolysis was confirmed by a sub-analysis of PCI post-fibrinolysis trials [4444. Dimopoulos K, Dudek D, Piscione F, Mielecki W, Savonitto S, Borgia F, Murena E, Manari A, Gaspardone A, Ochala A, Zmudka K, Bolognese L, Steg PG, Flather M, Di Mario C. Timing of events in STEMI patients treated with immediate PCI or standard medical therapy: implications on optimisation of timing of treatment from the CARESS-in-AMI trial. Int J Cardiol. 2012;154:275-281. ]. No studies, however, convincingly demonstrate that a delay between fibrinolysis and PCI after successful reperfusion impairs outcome while the time delay truly affecting prognosis also in these patients remains the time between start of symptoms of chest pain and fibrinolysis.

Rescue angiography/PCI

Rescue PCI for STEMI is defined as intervention performed on an infarct-related coronary artery after unsuccessful fibrinolysis. Accurate identification of patients for whom fibrinolytic therapy has not restored the infarct-related artery patency remains a problem in daily practice. Such assessment is usually done 60-90 minutes after initiation of thrombolysis and is based on clinical symptoms (chest pain relief) and electrocardiographic ST-segment resolution (resolution >50% suggests successful thrombolysis). Rescue PCI strategy has been tested in clinical trials. In the MERLIN trial, 307 patients who failed to achieve 50% electrocardiographic ST-segment resolution at 60 minutes following fibrinolytic therapy were randomised to either rescue PCI or conservative treatment (without repeat administration of fibrinolytic therapy) [4545. Sutton AG, Campbell PG, Graham R, Price DJ, Gray JC, Grech ED, Hall JA, Harcombe AA, Wright RA, Smith RH, Murphy JJ, Shyam-Sundar A, Stewart MJ, Davies A, Linker NJ, de Belder MA. A randomized trial of rescue angioplasty versus a conservative approach for failed fibrinolysis in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: the Middlesbrough Early Revascularization to Limit INfarction (MERLIN) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:287-296. ]. There was no difference in mortality at 30 days, but a lower rate of the composite endpoint (death/re-infarction/stroke/subsequent revascularisation/heart failure) was observed in the rescue PCI arm [4545. Sutton AG, Campbell PG, Graham R, Price DJ, Gray JC, Grech ED, Hall JA, Harcombe AA, Wright RA, Smith RH, Murphy JJ, Shyam-Sundar A, Stewart MJ, Davies A, Linker NJ, de Belder MA. A randomized trial of rescue angioplasty versus a conservative approach for failed fibrinolysis in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: the Middlesbrough Early Revascularization to Limit INfarction (MERLIN) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:287-296. ]. The REACT trial enrolled 427 patients with <50% ST-segment resolution at 90 minutes and showed higher event-free survival at 6 months in patients treated with rescue PCI compared to those randomised to either fibrinolytic re-administration or conservative therapy [4646. Gershlick AH, Stephens-Lloyd A, Hughes S, Abrams KR, Stevens SE, Uren NG, de Belder A, Davis J, Pitt M, Banning A, Baumbach A, Shiu MF, Schofield P, Dawkins KD, Henderson RA, Oldroyd KG, Wilcox R. Rescue angioplasty after failed thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2758-2768. ]. In a meta-analysis of 8 trials including 1,177 patients, rescue PCI was associated with no significant reduction in all-cause mortality but showed significant risk reduction in heart failure and re-infarction when compared with conservative treatment [4747. Wijeysundera HC, Vijayaraghavan R, Nallamothu BK, Foody JM, Krumholz HM, Phillips CO, Kashani A, You JJ, Tu JV, Ko DT. Rescue angioplasty or repeat fibrinolysis after failed fibrinolytic therapy for ST-segment myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:422-430. ]. The effectiveness of rescue angioplasty inspired the design of the STREAM trial, comparing in more than 1,800 patients primary versus an active rescue strategy applied in patients receiving tenecteplase (followed by rapid transfer for rescue PCI in 36.9% of the patients) [3030. Armstrong PW, Gershlick AH, Goldstein P, Wilcox R, Danays T, Lambert Y, Sulimov V, Rosell OF, Ostojic M, Welsh RC, Carvalho AC, Nanas J, Arntz HR, Halvorsen S, Huber K, Grajek S, Fresco C, Bluhmki E, Regelin A, Vandenberghe K, Bogaerts K, Van de Werf F. Fibrinolysis or primary PCI in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1379-1387. ]. Despite the absence of overall difference in mortality in the two groups, the significant increase in intracranial bleeding in the fibrinolysis group (dose had to be halved in patients over 75 years during the conduct of the trial) and the widespread availability of primary PCI make this alternative unappealing in clinical practice.

According to recent ESC STEMI Guidelines, rescue PCI is indicated immediately when fibrinolysis has failed <50% ST-segment resolution at 60-90 minutes or at any time in the presence of haemodynamic or electrical instability, or worsening ischaemia (recommendation Class I; level of evidence A). Emergency angiography and PCI is indicated in case of recurrent ischaemia or evidence of reocclusion after initial successful fibrinolysis. (recommendation Class I; level of evidence A). [211211. Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Bueno H, Caforio ALP, Crea F, Goudevenos JA, Halvorsen S, Hindricks G, Kastrati A, Lenzen MJ, Prescott E, Roffi M, Valgimigli M, Varenhorst C, Vranckx P, Widimský P; ESC Scientific Document Group 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2018;39:119-177. ].

Angiography and PCI for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction according to anticipated delay to mechanical reperfusion

- Primary PCI should be performed by an experienced team as soon as possible after STEMI diagnosis

- The preferred time limit from STEMI diagnosis to primary PCI (wire crossing) should be less than 90 minutes. This does not includepatients presenting directly in a PCI-capable hospital where the delay should be ≤60 min.

- Mechanical reperfusion and fibrinolysis are not alternative but complementary treatment modalities. When primary PCI is not available within the recommended time (the best organisational model will fail to achieve this target in rural or mountain areas far from primary PCI centres) fibrinolysis should be administered immediately. Then the patient should immediately be transferred (to avoid further delays in case of persistent chest pain or ECG changes) to a PCI-capable hospital where angiography and PCI should be performed within 24 hours.

Procedure technique

ACCESS SITE SELECTION

The selection of the coronary revascularisation method and the technique of performing primary PCI are not significantly different from those routinely used during elective PCI. Femoral approach is still common but a transradial approach should be preferred to decrease bleeding complications associated with the aggressive antiplatelet and antithrombotic treatment administered in the STEMI setting. The femoral and radial access techniques were described in detail in Chapter 1.04.

Importantly, the transradial approach was shown to be associated not only with a reduction of acute bleeding events, but also with a mortality reduction in STEMI patients. Thus, according to current ESC STEMI Guidelines (I; A) [211211. Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Bueno H, Caforio ALP, Crea F, Goudevenos JA, Halvorsen S, Hindricks G, Kastrati A, Lenzen MJ, Prescott E, Roffi M, Valgimigli M, Varenhorst C, Vranckx P, Widimský P; ESC Scientific Document Group 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2018;39:119-177. ] and ESC/EACTS Myocardial Revascularization Guidelines (IIa; A) [168168. Windecker S, Kolh P, Alfonso F, Collet JP, Cremer J, Falk V, Filippatos G, Hamm C, Head SJ, Juni P, Kappetein AP, Kastrati A, Knuuti J, Landmesser U, Laufer G, Neumann FJ, Richter DJ, Schauerte P, Sousa Uva M, Stefanini GG, Taggart DP, Torracca L, Valgimigli M, Wijns W, Witkowski A. 2014 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization: The Task Force on Myocardial Revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS)Developed with the special contribution of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI). Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2541-2619. ], the use of the transradial access during primary PCI for STEMI should be preferred, if performed by an experienced radial operator. The transradial approach also allows for early ambulation and reduction of total hospitalisation cost. The success rate of primary PCI via the transradial approach is similar to that observed with the femoral approach. Importantly, in experienced centres, the use of radial access in the STEMI setting is not associated with prolongation of door-to-balloon time and procedure time [4848. Pancholy S, Patel T, Sanghvi K, Thomas M, Patel T. Comparison of door-to-balloon times for primary PCI using transradial versus transfemoral approach. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;75:991-995. , 4949. Weaver AN, Henderson RA, Gilchrist IC, Ettinger SM. Arterial access and door-to-balloon times for primary percutaneous coronary intervention in patients presenting with acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;75:695-699. , 5050. Siudak Z, Zawislak B, Dziewierz A, Rakowski T, Jakala J, Bartus S, Noworolnik B, Zasada W, Dubiel JS, Dudek D. Transradial approach in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction treated with abciximab results in fewer bleeding complications: data from EUROTRANSFER registry. Coron Artery Dis. 2010;21:292-297. ]. On the other hand, the use of radial access during more complex procedures is not ideal due to weaker guiding catheter back-up and the limited possibility of larger than 6 Fr guiding catheters being used during the procedure, especially in radial arteries with a small diameter (smaller women, patients with previous transradial procedures) [5151. Bazemore E, Mann JT, III. Problems and complications of the transradial approach for coronary interventions: a review. J Invasive Cardiol. 2005;17:156-159. ]. Cardiogenic shock or haemodynamic compromise should not be considered as absolute contraindications for the transradial approach, provided that the radial artery is palpable, possibly after insertion of an intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) or left ventricular assist device (LVAD) via the femoral artery.

In a meta-analysis of 12 studies (randomised, case-control, and cohort studies) involving 3,324 patients the transradial approach during primary PCI in comparison to femoral access was associated with a significant reduction of major bleeding, death and the composite endpoint of death, MI, or stroke. However, the fluoroscopic time was longer, and access site crossover was more frequent for the transradial approach [5252. Vorobcsuk A, Konyi A, Aradi D, Horvath IG, Ungi I, Louvard Y, Komocsi A. Transradial versus transfemoral percutaneous coronary intervention in acute myocardial infarction Systematic overview and meta-analysis. Am Heart J. 2009;158:814-821. ].

In the MATRIX study, a total of 8,404 patients with acute coronary syndromes, with or without ST-segment elevation were randomised to radial and femoral access for coronary angiography / PCI [169169. Valgimigli M, Gagnor A, Calabro P, Frigoli E, Leonardi S, Zaro T, Rubartelli P, Briguori C, Ando G, Repetto A, Limbruno U, Cortese B, Sganzerla P, Lupi A, Galli M, Colangelo S, Ierna S, Ausiello A, Presbitero P, Sardella G, Varbella F, Esposito G, Santarelli A, Tresoldi S, Nazzaro M, Zingarelli A, de Cesare N, Rigattieri S, Tosi P, Palmieri C, Brugaletta S, Rao SV, Heg D, Rothenbuhler M, Vranckx P, Juni P. Radial versus femoral access in patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing invasive management: a randomised multicentre trial. Lancet. 2015;385:2465-2476. ]. The rates of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) as well as net cardiovascular events (combined ischaemic and bleeding events) were lower in the radial access group. The difference was driven by BARC major bleeding unrelated to coronary artery bypass graft surgery (1.6% vs 2.3%, rate ratio (RR) 0.67, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.49-0.92, p=0.013) and all-cause mortality (1.6% vs 2.2%, RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.53-0.99, p=0.045). Benefits in terms of mortality reduction were confirmed also by an updated meta-analysis of studies comparing radial and femoral approach in acute coronary syndromes [169169. Valgimigli M, Gagnor A, Calabro P, Frigoli E, Leonardi S, Zaro T, Rubartelli P, Briguori C, Ando G, Repetto A, Limbruno U, Cortese B, Sganzerla P, Lupi A, Galli M, Colangelo S, Ierna S, Ausiello A, Presbitero P, Sardella G, Varbella F, Esposito G, Santarelli A, Tresoldi S, Nazzaro M, Zingarelli A, de Cesare N, Rigattieri S, Tosi P, Palmieri C, Brugaletta S, Rao SV, Heg D, Rothenbuhler M, Vranckx P, Juni P. Radial versus femoral access in patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing invasive management: a randomised multicentre trial. Lancet. 2015;385:2465-2476. ].

Physicians performing primary PCI should be familiar with both the transradial and femoral approach, as the use of particular approach might be limited due to difficult anatomy or concomitant severe peripheral vascular disease.

CATHETER AND GUIDEWIRE SELECTION

Coronary angiography can be performed with standard diagnostic catheters, although, angiography of the infarct-related artery can also be performed with a guiding catheter in order to save the time needed for catheter exchange. The properties of different guiding catheters and guidewires are described in Chapter 3.03. Standard Judkins and Extra Back-Up guiding catheters are preferred, but other guiding catheters (for example Amplatz), selected based on orifice configuration, anatomy of the artery and location of atherosclerotic lesions, are useful if a more effective guiding catheter back-up is needed. Proper guiding catheter selection increases the success rate and decreases procedure time.

The first attempt of passing through the site of occlusion should be made with soft non-hydrophilic guidewires. Use of soft guidewires limits the risk of distal vessel dissection and facilitates vessel true-lumen finding. If the passage with a soft guidewire is not successful, especially in calcified and tightly narrowed vessels, hydrophilic or polymer-jacketed wires and/or the support of microcatheters should be the second choice.

Aspiration thrombectomy technique

- Use of manual aspiration catheters should be limited to occluded infarct-related arteries or arteries with established distal flow and high thrombus burden after guidewire crossing

- Successful thrombectomy allows better visualisation of the atherosclerotic lesion and distal part of the infarct-related artery

- Aspiration should be started 2 cm before the occlusion or the lesion with thrombus

- Multiple slow-passage technique should be used, with a stop on the thrombus site and continuation of suction distally to the site of occlusion (if possible). Two or three passages are recommended

- The thrombectomy catheter must be removed with aspiration, even into the guiding catheter, and then the blood from the guiding catheter must also be aspirated.

- Suction success should be confirmed by presence of thrombus on the filter

- If greater suction force is needed (bigger arteries, organised thrombus) larger size catheters (7 Fr) or catheters with active thrombus fragmentation can be considered

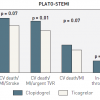

PRIMARY PCI STRATEGY

Primary PCI should be performed immediately after coronary angiography within the culprit lesion. The optimal technique of primary PCI should be chosen after evaluation of the infarct-related artery flow, thrombus burden and vessel size ( Figure 4 ). Routine use of stents during primary PCI for STEMI is currently recommended. Preferably, the technique of direct stenting (without prior balloon dilatation) should be used if the distal part of the vessel is visible, as it is associated with improvement of reperfusion parameters and a reduced risk of no-reflow phenomenon during primary PCI [5353. Loubeyre C, Morice MC, Lefevre T, Piechaud JF, Louvard Y, Dumas P. A randomized comparison of direct stenting with conventional stent implantation in selected patients with acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:15-21. , 5454. Napodano M, Ramondo A, Tarantini G, Peluso D, Compagno S, Fraccaro C, Frigo AC, Razzolini R, Iliceto S. Predictors and time-related impact of distal embolization during primary angioplasty. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:305-313. , 5555. Dziewierz A, Siudak Z, Rakowski T, Kleczynski P, Zasada W, Dubiel JS, Dudek D. Impact of direct stenting on outcome of patients with st-elevation myocardial infarction transferred for primary percutaneous coronary intervention (from the EUROTRANSFER registry). Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2013. ]. The use of simple manual aspiration catheters as an alternative to standard balloon dilatation may facilitate direct stenting, especially in occluded arteries and vessels with large thrombus burden. However, current ESC STEMI Guidelines recommended manual thrombectomy in STEMI as Class III;A (routine use of thrombus aspiration is not recommended) [211211. Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Bueno H, Caforio ALP, Crea F, Goudevenos JA, Halvorsen S, Hindricks G, Kastrati A, Lenzen MJ, Prescott E, Roffi M, Valgimigli M, Varenhorst C, Vranckx P, Widimský P; ESC Scientific Document Group 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2018;39:119-177. ]. The strategy of mechanical protection and stent selection in different subsets of patients is described in the following paragraphs.