Introduction

Endovascular therapy has emerged as a less invasive alternative to open surgery for stroke prevention in patients with obstructive disease of the supra-aortic arteries. However, differences in endpoint definitions, timing of assessments and standards of reporting have hampered comparisons of results across single-centre experiences, registries and randomised controlled trials.

As an example, a direct comparison of the major stroke rate observed in the CREST (The Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy versus Stenting Trial) and ICSS [22. International Carotid Stenting Study investigators, Ederle J, Dobson J, Featherstone RL, Bonati LH, van der Worp HB, de Borst GJ, Lo TH, Gaines P, Dorman PJ, Macdonald S, Lyrer PA, Hendriks JM, McCollum C, Nederkoorn PJ, Brown MM. Carotid artery stenting compared with endarterectomy in patients with symptomatic carotid stenosis (International Carotid Stenting Study): an interim analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;375:985-997. ] (International Carotid Stenting Study) trials is problematic because of differences in the definition of neurological outcome after carotid endarterectomy or stenting. Accordingly, in the CREST [11. Brott TG, Hobson RW, Howard G, Roubin GS, Clark WM, Brooks W, Mackey A, Hill MD, Leimgruber PP, Sheffet AJ, Howard VJ, Moore WS, Voeks JH, Hopkins LN, Cutlip DE, Cohen DJ, Popma JJ, Ferguson RD, Cohen SN, Blackshear JL, Silver FL, Mohr JP, Lal BK, Meschia JF; CREST Investigators. Stenting versus endarterectomy for treatment of carotid-artery stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:11-23. ] trial, the primary endpoint was a composite of stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), or death from any cause during the 30-day periprocedural period or any ipsilateral stroke beyond 30 days and up to four years. Stroke was defined as an acute neurological ischaemic event lasting at least 24 hours with focal signs and symptoms. The stroke endpoint was adjudicated by at least two neurologists blinded to treatment. A stroke was defined as major in the presence of a National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score of 9 or higher 90 days after the procedure.

In the ICSS trial, stroke was defined as a rapidly developing clinical syndrome of focal disturbance of cerebral function lasting more than 24 hours or leading to death with no apparent cause other than that of vascular origin. Stroke was classified as fatal if death attributed to stroke occurred within 30 days of onset of stroke. Stroke or cranial nerve palsy were classified as disabling if there was an increase in the Rankin score to 3 or more, attributable to the event at 30 days after onset. The remaining non-fatal strokes were classified as non-disabling.

The recognition that across-trial consistency would facilitate the evaluation of established therapies, such as carotid endarterectomy (CEA) and carotid artery stenting (CAS), and of novel endovascular technologies, has prompted efforts for unification of clinical endpoint definitions. As a result, consensus articles on clinical endpoints in coronary stent trials and in peripheral endovascular revascularisation trials have been published.

The DEFINE group has recently proposed clinical endpoint definitions in supra-aortic trunk revascularisation trials[55. Nedeltchev K, Pattynama PM, Biamino G, Diehm N, Jaff MR, Hopkins LN, Ramee S, van Sambeek M, Talen A, Vermassen F, Cremonesi A. Standardized definitions and clinical endpoints in carotid artery and supra-aortic trunk revascularization trials. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;76:333-44.

Clinical endpoints in carotid artery and supra-aortic trunk revascularisation trials.]. This group comprised angiologists, cardiologists, radiologists, vascular surgeons, neurosurgeons, neurologists and other medical specialists from Europe and the United States who were experts in the diagnosis and treatment of patients with atherosclerotic disease of the supra-aortic arteries. Following review of the literature and multiple meetings, a DEFINE consensus document was published [33. Cutlip DE, Windecker S, Mehran R, Boam A, Cohen DJ, van Es GA, Steg PG, Morel MA, Mauri L, Vranckx P, McFadden E, Lansky A, Hamon M, Krucoff MW, Serruys PW. Academic Research Consortium. Clinical end points in coronary stent trials: a case for standardized definitions. Circulation. 2007;115:2344–51.

Clinical endpoints in coronary stent trials., 44. Diehm N, Pattynama PM, Jaff MR, Cremonesi A, Becker GJ, Hopkins LN, Mahler F, Talen A, Cardella JF, Ramee S, van Sambeek M, Vermassen F, Biamino G. Clinical endpoints in peripheral endovascular revascularization trials: a case for standardized definitions. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2008;36:409–19.

Clinical endpoints in peripheral endovascular revascularisation trials.].

The proposed definitions encompass baseline clinical manifestations, anatomical characteristics, clinical and radiological outcomes, complications, standards of reporting, and timing of assessment. If, on consideration, there is broad consensus among the multidisciplinary scientific members and the regulatory authorities, the proposed definitions may find broad adoption in future clinical investigations.

Proposed baseline and endpoint definitions

PATIENT CLINICAL AND ANATOMICAL BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS

For a correct assessment of supra-aortic revascularisation trials it is critical to define precisely clinical and anatomical baseline characteristics of the enrolled population. Accordingly, while the outcomes of CEA may be largely influenced by the clinical characteristics of the patient (i.e., comorbidities), the outcomes of CAS are mainly affected by the anatomical characteristics of the enrolled population.

BASELINE CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS

It is essential to identify patient characteristics for specific treatment concepts and to provide a definition of a successful intervention. Indications and expected results are different for the treatment of clinically asymptomatic and for clinically symptomatic patients. Outcome measures should be appropriate for the goals of the therapy.

The pretreatment evaluation must include the neurologic status of the patient, objective and quantitative measures of disease severity, and an evaluation of risk factors which may predict treatment failure, complications and progression of disease. This includes clinical and anatomical criteria.

STENOSIS OF THE INTERNAL CAROTID ARTERY (ICA)

Neurological evaluation

Since it may be challenging to know whether a neurological symptom is or is not related to a carotid stenosis, it is critical that all patients undergoing carotid revascularisation are examined by a neurologist.

A carotid stenosis is considered symptomatic in the presence of transient ischaemic attack (TIA), stroke, or ischaemic ocular symptoms in the previous 6 months. As the risk for stroke recurrence decreases over time [66. Rothwell PM, Eliasziw M, Gutnikov SA, Warlow CP, Barnett HJ. Sex difference in the effect of time from symptoms to surgery on benefit from carotid endarterectomy for transient ischemic attack and nondisabling stroke. Stroke. 2004; 35: 2855–2861. ], patients with neurological symptoms older than 6 months should be considered as asymptomatic. It is recommended that all patients undergo a preoperative CT-scan or MRI to have a baseline cerebral status and to detect “silent” brain infarctions. Patients with “silent” lesions in the territory of the affected carotid on cerebral imaging should still be considered asymptomatic, although at higher risk of stroke compared with patients with no cerebral lesions.

Neurological symptoms which may be related to a carotid stenosis include:

Hemispheric symptoms: temporary or permanent sensory or motor dysfunction, hemianopia, aphasia, apraxia, agnosia, or neglect. A differentiation is made based on the reversible [77. Easton JD, Saver JL, Albers GW, Alberts MJ, Chaturvedi S, Feldmann E, Hatsukami TS, Higashida RT, Johnston SC, Kidwell CS, Lutsep HL, Miller E, Sacco RL. Definition and evaluation of transient ischemic attack: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; and the Interdisciplinary Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease. The American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this statement as an educational tool for neurologists. Stroke. 2009;40:2276–93.

Definition and evaluation of transient ischaemic attack.] (TIA) or the permanent character of the cerebral injury (ischaemic stroke). A further differentiation is made based on stroke severity (major or minor stroke) and functional outcome at 6 months (non-disabling, disabling, or fatal stroke). Hemispheric symptoms can be ipsilateral to the ICA stenosis or contralateral. Only patients with symptoms related to the ipsilateral hemisphere should be considered symptomatic.

Ocular symptoms: emboli to the ophthalmic artery can cause temporary or permanent ocular symptoms, most commonly partial or total loss of visual acuity. On the basis of the symptom duration, ocular symptoms are classified as transient retinal ischaemia (<24 hours duration) or retinal infarction (>24 hours duration).

Cerebral hypoperfusion: On rare occasions, an ICA stenosis may cause regional or global cerebral hypoperfusion based solely on haemodynamic effects. Predisposing factors are an occlusion or severe stenosis of the contralateral carotid artery or poor/absent collateral circulation (“isolated hemisphere”). The hypoperfusion may become manifest as transient (“low-flow” TIA) or permanent (haemodynamic stroke) hemispheric symptoms. These symptoms are difficult to interpret and the relationship with a stenotic carotid artery should always be made with caution.

Few specific neurological presentations, such as “crescendo TIAs” (multiple recurrent TIAs over hours to days) and “stroke in progress”, represent an indication for emergent carotid revascularisation. In this setting, the revascularisation, although highly beneficial, is associated with a higher rate of neurological complications compared to stable patients. These patients have commonly been excluded from randomised trials. If included in a protocol, then the outcomes of those patients should be analysed separately [88. Bond R, Rerkasem K, Rothwell PM. Systematic review of the risks of carotid endarterectomy in relation to the clinical indication for and timing of surgery. Stroke. 2003; 34: 2290–2301. ].

The shorter the time between neurological symptom and carotid revascularisation, the greater the benefit in terms of (recurrent) stroke prevention, but at the same time the greater the risk of periprocedural stroke [99. Naylor AR. Time is brain! Surgeon. 2007; 5: 23–30. ]. Therefore, if symptomatic patients are randomised to two different treatment strategies, then the time window between randomisation and treatment should be defined. In any case, documentation of (1) time from the index event to treatment and (2) time from the most recent event to the treatment (if the most recent event is not identical to the index event) should be provided.

A physician certified in the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) should assess the actual neurological status before the procedure [1010. Brott T, Adams HPJ, Olinger CP, Marler JR, Barsan WG, Biller J, Spilker J, Holleran R, Eberle R, Hertzberg V, et al. Measurements of acute cerebral infarction: A clinical examination scale. Stroke. 1989; 20: 864–870. ].

Evaluation of risk factors: risk factors play an important role in the chance of procedural failure, short and long-term complications, progression of disease, and recurrence of symptoms. The risk factors can be differentiated into general and procedural risk factors. The latter are different for CEA and for CAS.

- General risk factors: atherosclerotic risk factors and comorbidities which are pertinent regardless of treatment strategy: age, gender, race, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, diabetes mellitus, current smoking (including the previous 5 years), ischaemic heart disease, congestive heart failure, renal insufficiency, and severe pulmonary disease.

- Procedural risk factors which need attention are restenosis after previous CEA or CAS, previous neck surgery, post radiation stenosis, cervical immobility, location of the ICA stenosis above the level of the C2 vertebral body, stenosis of nonarteriosclerotic origin, contralateral carotid occlusion, age > 80 years, severe aorto-iliac obstructive disease, complex lesion categories (calcified or soft plaques, angled lesions, aortic arch type II or III, proximal and/or distal kinking), concomitant stenosis of the common and/or distal internal carotid and/or vertebral arteries which is more severe than the target lesion.

Medication

Pre-, intra-, and post-procedural medication can influence outcome. Therefore, it is mandatory to specify the following medication: antiplatelets, heparin or low-molecular weight heparins, vitamin K-antagonists, direct thrombin inhibitors, statins, and antihypertensive drugs.

Other clinical evaluation

- Neuropsychological testing: a recent systematic review of 32 neurocognition trials has come to the conclusion that assessment of cognition after carotid revascularisation might be influenced by many confounding factors such as learning effect, type of test, type of patients, and control group, which are often minimised in their importance [1111. De Rango P, Caso V, Leys D, Paciaroni M, Lenti M, Cao P. The role of carotid artery stenting and carotid endarterectomy in cognitive performance: A systematic review. Stroke. 2008; 39: 3116–3127. ]. Consequently, no specific recommendation on neuropsychological testing can be made at this point. Larger appropriately designed studies powered to assess cognition after carotid revascularisation might change this view.

- Quality of life: quality of life (QoL) assessment gives information which is not provided by traditional outcome scores [1212. Fischer U, Anca D, Arnold M, Nedeltchev K, Kappeler L, Ballinari P, Schroth G, Mattle HP. Quality of life in stroke survivors after local intra-arterial thrombolysis. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2008; 25: 438–444. ]. Assessment of QoL in supra-aortic revascularisation trials using generic (e.g., EuroQol [1313. EuroQol–a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. The EuroQol Group. Health Policy. 1990; 16: 199–208. ]) or specific questionnaires (e.g., Stroke Specific Quality of Life (SS-QoL [1414. Williams LS, Weinberger M, Harris LE, Clark DO, Biller J. Development of a stroke-specific quality of life scale. Stroke. 1999; 30: 1362–1369. ]) should be encouraged. Generic QoL measures are well-validated and allow for comparisons which are not confined to a specific health condition. Specific QoL questionnaires are more sensitive to meaningful changes in post-stroke QoL and may thus aid in identifying specific aspects of post-stroke function which trialists can target to improve patients’ QoL after stroke.

Internal carotid artery stenosis

- Pre-intervention examination by a neurologist is mandatory

- Symptomatic carotid stenosis includes TIA, stroke or ischaemic ocular symptoms within the previous 6 months

- Clinically silent radiological lesions or symptoms>6 months are considered as asymptomatic

- A stenosis of 50% or greater is considered haemodynamically significant

- The NASCET criteria should be used to grade the stenosis

- Symptomatic patients with 50-99% stenosis and asymptomatic patients with 60-99% stenosis are potential candidates for revascularization

STENOSIS OF THE VERTEBRAL ARTERY (VA)

Neurological evaluation

As the clinical evaluation of symptoms from the vertebrobasilar territory is even more challenging than the evaluation of carotid symptoms, a pre-intervention examination by a neurologist is mandatory. A difference should be made between symptomatic and asymptomatic patients with stenoses of the vertebral arteries. There is no evidence supporting treatment of asymptomatic patients with VA stenosis. Symptoms related to the vertebrobasilar territory are most often combinations of brainstem, cerebellar, thalamic, and posterior cerebral artery symptoms: coma, oculomotor nerve palsy, diplopia, nystagmus, vertigo, dizziness, ataxia, visual field loss, hemiparesis or tetraparesis with or without involvement of cranial nerves (e.g., locked-in syndrome), pure hemisensory loss, and disorders of colour vision, face recognition or memory.

The study report should include a description of the symptoms for which these patients were treated.

Vertebral artery stenosis

- Pre-intervention examination by a neurologist is mandatory

- Symptoms include: coma, cranial nerve palsy, diplopia, nystagmus, vertigo, dizziness, ataxia, visual field loss, hemiparesis or tetraparesis, pure hemisensory loss, and disorders of colour vision, face recognition or memory

- Only symptomatic patients with stenosis are candidates for revascularisation

Reporting of general and procedural risk factors, medication or other clinical evaluation does not differ from that of patients with stenosis of the ICA.

STENOSIS OR OCCLUSION OF THE SUBCLAVIAN ARTERY (SA)

Physical evaluation

A differentiation should be made according to the indication for which the SA stenosis is treated. Symptoms related to SA stenosis are:

Arm or brain embolic events: acute ischaemia in the vertebrobasilar territory, blue digit, and so forth.

Arm claudication: fatigue on exertion in the arm. Because of the rich collateral circulation, arm claudication rarely occurs as a significant symptom. Symptoms which lead to significant disability or decreased QoL are considered significant.

Vertebral-subclavian steal syndrome: retrograde blood flow in the VA associated with proximal ipsilateral stenosis or occlusion of the SA. Neurological symptoms occur as a consequence of ischaemia in the vertebrobasilar territory during or immediately following exercise of the ipsilateral arm [1515. Reivich M, Holling HE, Roberts B, Toole JF. Reversal of blood flow through the vertebral artery and its effect on cerebral circulation. N Engl J Med. 1961; 265: 878–885. ].

Coronary-subclavian steal syndrome: in patients who have undergone coronary artery bypass surgery with the use of an internal mammary artery graft, an SA stenosis may cause angina due to the insufficient perfusion of the mammary artery [1616. Tyras DH, Barner HB. Coronary-subclavian steal. Arch Surg. 1977; 112: 1125–1127. ].

Subclavian steal syndrome in patients with a high-output dialysis arteriovenous fistula: symptoms of vertebrobasilar insufficiency with reversal of flow in the ipsilateral VA in patients who are dialysis-dependent and who have an arteriovenous fistula in the arm ipsilateral to the SA stenosis [1717. Schenk WGR. Subclavian steal syndrome from high-output brachiocephalic arteriovenous fistula: a previously undescribed complication of dialysis access. J Vasc Surg. 2001; 33: 883–885. ].

Subclavian artery stenosis

- Symptoms include: Arm or brain embolic events, srm claudication, vertebral-subclavian steal syndrome, coronary-subclavian steal syndrome,, and subclavian steal syndrome in patients with a high-output dialysis arteriovenous fistula

- Symptomatic patients with stenosis or occlusion are potential candidates for revascularisation

BASELINE ANATOMICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Baseline anatomical characteristics should be reported for all enrolled patients. They should include the pertinent characteristics of the stenosis under consideration and the proximal inflow status including the aortic arch configuration. For ICA and SA stenoses, some additional considerations apply.

DESCRIPTION OF THE STENOSIS

Site of stenosis

It should be specified whether or not the lesion involves the origin/ostium of the specific artery.

Degree of stenosis

Artery diameter reduction of 50% or more is usually considered to be haemodynamically significant. Degree of stenosis can be assessed utilising the following measurement techniques:

1. Catheter angiography (intra-arterial digital subtraction angiography) in the projection showing the maximum stenosis grade [1818. North American symptomatic carotid endarterectomy trial. Methods, patient characteristics, and progress. Stroke. 1991; 22: 711–720. ];

2. Contrast-enhanced multislice computed tomography angiography (CT-angiography);

3. Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance angiography (MR-angiography);

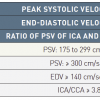

4. For ICA stenosis, duplex ultrasound can be used to study the absolute intra-stenotic peak systolic velocity (PSV), end-diastolic velocity (EDV) values at a Doppler angle of 45°–60° [1919. Grant EG, Benson CB, Moneta GL, Alexandrov AV, Baker JD, Bluth EI, Carroll BA, Eliasziw M, Gocke J, Hertzberg BS, Katanick S, Needleman L, Pellerito J, Polak JF, Rholl KS, Wooster DL, Zierler RE. Carotid artery stenosis: Gray-scale and Doppler US diagnosis–Society of radiologists in ultrasound consensus conference. Radiology. 2003; 229: 340–346. , 2020. Oates CP, Naylor AR, Hartshorne T, Charles SM, Fail T, Humphries K, Aslam M, Khodabakhsh P. Joint recommendations for reporting carotid ultrasound investigations in the United Kingdom. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2009;37:251–61.

Recommendations for reporting carotid ultrasound investigations.]. The following are the suggested values:

- >50% diameter stenosis of the ICA: PSV > 125 cm/s;

- >70% diameter stenosis of the ICA: PSV > 230 cm/s;

- >70% diameter stenosis of the remaining supra-aortic arteries: the ratio of intra-stenotic PSV to pre-stenotic PSV is >2.4 [2121. Ranke C, Hendrickx P, Roth U, Brassel F, Creutzig A, Alexander K. Color and conventional image-directed Doppler ultrasonography: accuracy and sources of error in quantitative blood flow measurements. J Clin Ultrasound. 1992; 20: 187–193. ].

Vascular laboratories are encouraged to validate their own cut-off values. The inclusion of centres with certified ultrasonographers will improve the data quality in revascularisation trials.

Extent of calcification at the stenosis

The extent of calcification of the target lesion does not appear to increase the risk of periprocedural complications in patients undergoing endovascular therapy. Nevertheless, most studies collect data on the extent of calcification. There is no quantitative way defined in the literature to separate these categories by fluoroscopy and angiography. However, qualitative definitions have been used in both the coronary and the carotid literature [2222. Mintz GS, Popma JJ, Pichard AD, Kent KM, Satler LF, Chuang YC, Ditrano CJ, Leon MB. Patterns of calcification in coronary artery disease. A statistical analysis of intravascular ultrasound and coronary angiography in 1155 lesions. Circulation. 1995; 91: 1959–1965. ]. The generally reported categories are none, mild (trace shadowing), moderate (luminal irregularity), and severe (diffuse calcification). The DEFINE group believe that, until a quantitative measure of calcification is defined, this qualitative definition will suffice.

INFLOW STATUS

Classification of the aortic arch type

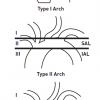

The procedural success and complication rates of endovascular supra-aortic interventions depend on the anatomy of the aortic arch [2323. Bazan HA, Pradhan S, Mojibian H, Kyriakides T, Dardik A. Increased aortic arch calcification in patients older than 75 years: implications for carotid artery stenting in elderly patients. J Vasc Surg. 2007; 46: 841–845. ]. In the context of CAS, various classification schemes have been proposed for the aortic arch type[2424. Haery C,Yadav JS. Percutaneous carotid artery stenting. In: HerrrmannHC, editor. Interventional Cardiology Percutaneous Noncoronary Intervention. Totowa, NJ, Humana Press. 2005. pp 329. , 2525. Lam RC, Lin SC, DeRubertis B, Hynecek R, Kent KC, Faries PL. The impact of increasing age on anatomic factors affecting carotid angioplasty and stenting. J Vasc Surg. 2007; 45: 875–880. ]. We recommend a simple angiographic classification which is based on the position of the origin of the brachiocephalic vessels relative to the superior and the inferior aortic arch lines, with the aortic arch seen in profile (recommended 30°–90° LAO) [2626. Myla S. A simplified scheme for classifying aortic arches to facilitate carotid access during stenting (abstract). Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2006; 7: 89–90. ] ( Figure 1 ):

- Type 1 arch: the origins of the great vessels are at the level of the superior arch line (SAL).

- Type 2 arch: the origins of the great vessels are between the SAL and the inferior arch line (IAL).

- Type 3 arch: the origins of the great vessels (in the case presented in Figure 1, this is the IA) are below the level of the IAL.

The classification emphasises the importance of the angle between the top of the aortic arch and the origin of the vessel to be negotiated, steep angles being more difficult to access.

Aortic arch atherosclerosis

Distinctions between absent, slight, moderate, and severe atherosclerosis should be made, based on calcification and/or surface irregularity. Calcification of the aortic arch may be a predictor of periprocedural complications because of embolisation during supra-aortic catheter interventions.

SPECIFIC CONSIDERATIONS FOR ICA STENOSES

Carotid bulb

The carotid bulb includes the first segment of the ICA. Uncommonly, carotid stenoses may straddle the carotid bulb extending proximally into the common carotid artery and distally into the cervical ICA.

Grading of carotid artery stenosis

Various competing grading systems for ICA stenosis are in use which may yield different results when applied to a single given patient [2727. Staikov IN, Arnold M, Mattle HP, Remonda L, Sturzenegger M, Baumgartner RW, Schroth G. Comparison of the ECST, CC, and NASCET grading methods and ultrasound for assessing carotid stenosis. European Carotid Surgery Trial. North American symptomatic carotid endarterectomy trial. J Neurol . 2000; 247: 681–686. ]. To avoid ambiguity, it is desirable to use the criteria of the North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial (NASCET) [1818. North American symptomatic carotid endarterectomy trial. Methods, patient characteristics, and progress. Stroke. 1991; 22: 711–720. ]. The NASCET criteria relate the diameter of the residual lumen at the site of the stenosis (A) to that of the more distal, normally appearing ICA (B) ( Figure 2 ). Patients with a symptomatic 50%–99% ICA stenosis or an asymptomatic 60%–99% ICA stenosis are considered as possible candidates for revascularisation.

Outflow status, cerebral circulation

Before any revascularisation procedure, it is recommended to image the ICA to its bifurcation into the anterior and the middle cerebral arteries. The aim is to rule out additional distal stenosis (tandem stenosis).

A special situation may occur as a result of a very tight, preocclusive stenosis. There is a diminished antegrade flow into a collapsed ICA which appears like a thin string (“carotid string”) on arteriography. After successful recanalisation of the preocclusive stenosis, the ICA may regain its normal diameter [2828. Kashyap VS,Clair DG. Carotid string sign. J Vasc Surg. 2006; 43: 401. , 2929. Pappas JN. The angiographic string sign. Radiology. 2002; 222: 237–238. ]. String sign should be evaluated separately [3030. Rothwell PM, Gutnikov SA, Warlow CP. Reanalysis of the final results of the European carotid surgery trial. Stroke. 2003; 34: 514–523. ].

Plaque morphology of the carotid artery stenosis

Severely calcified or ulcerated atherosclerotic plaques are not associated with an increased periprocedural risk. However, preliminary evidence suggests that plaques with a thin or disrupted fibrous cap, a large lipid core or intra-plaque haemorrhages are prone to rupture and embolisation. Current imaging modalities such as high-resolution B-mode ultrasound and contrast-enhanced CT and MRI are not only able to grade the vessel accurately but also to show the plaque morphology and composition [3131. de Weert TT, Ouhlous M, Meijering E, Zondervan PE, Hendriks JM, van Sambeek MR, Dippel DW, van der Lugt A. In vivo characterization and quantification of atherosclerotic carotid plaque components with multidetector computed tomography and histopathological correlation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006; 26: 2366–2372. , 3232. Kwee RM, van Oostenbrugge RJ, Hofstra L, Teule GJ, van Engelshoven JM, Mess WH, Kooi ME. Identifying vulnerable carotid plaques by noninvasive imaging. Neurology. 2008; 70: 2401–2409. ]. The main disadvantage of B-mode ultrasound is its modest intra- and interobserver reproducibility [3333. Mayor I, Momjian S, Lalive P, Sztajzel R. Carotid plaque: Comparison between visual and grey-scale median analysis. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2003; 29: 961–966. ]. Computer-assisted analysis of the grey-scale median (GSM) values allows for operator-independent analysis of the plaque echogenicity and hence the plaque structure. Previous studies have reported a close correlation between the GSM values and the presence of clinical symptoms, although the correlation with histopathological findings has not been reliable [3434. Hashimoto H, Tagaya M, Niki H, Etani H. Computer-Assisted analysis of heterogeneity on b-mode imaging predicts instability of asymptomatic carotid plaque. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009; 28: 357–364. , 3535. Reiter M, Effenberger I, Sabeti S, Mlekusch W, Schlager O, Dick P, Puchner S, Amighi J, Bucek RA, Minar E, Schillinger M. Increasing carotid plaque echolucency is predictive of cardiovascular events in high-risk patients. Radiology. 2008; 248: 1050–1055. , 3636. Reiter M, Horvat R, Puchner S, Rinner W, Polterauer P, Lammer J, Minar E, Bucek RA. Plaque imaging of the internal carotid artery-correlation of B-flow imaging with histopathology. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2007; 28: 122–126. ]. Plaque characteristics as assessed with MRI have been shown to predict subsequent neurologic events [3737. Altaf N, Daniels L, Morgan PS, Auer D, MacSweeney ST, Moody AR,Gladman JR. Detection of intraplaque hemorrhage by magnetic resonance imaging in symptomatic patients with mild to moderate carotid stenosis predicts recurrent neurological events. J Vasc Surg. 2008; 47: 337–342. , 3838. Takaya N, Yuan C, Chu B, Saam T, Underhill H, Cai J, Tran N, Polissar NL, Isaac C, Ferguson MS, Garden GA, Cramer SC, Maravilla KR, Hashimoto B, Hatsukami TS. Association between carotid plaque characteristics and subsequent ischemic cerebrovascular events: A prospective assessment with MRI–initial results. Stroke. 2006; 37: 818–823. ], but it is unknown to what extent plaque morphology can be taken as an independent risk factor for stroke in addition to carotid artery obstruction. For instance, it is unclear if a symptomatic patient with a lesion consistent with a vulnerable plaque but a <50% diameter stenosis would benefit from revascularisation. Consequently, reporting of the pretreatment plaque morphology is not mandatory. If imaging of the carotid plaque is available, it should be reported.

SPECIFIC CONSIDERATIONS FOR SA STENOSIS OR OCCLUSION

Complete SA occlusions may be treated and the length of the occluded segment should be recorded.