Pulmonary embolism

SUMMARY

In contrast to the systemic circulation, the pulmonary circulation is a high-flow low-resistance system. The right ventricle responds to an increase in resistance within the pulmonary vascular bed by increasing right ventricular pressure to preserve cardiac output.

Pulmonary embolism (PE) is a relatively common cardiovascular emergency, yet it is a rare but significant complication of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Data about the incidence of PE in association with PCI is limited. A small study described that PE was the reason for death in 1.7% of patients, who died during their acute hospitalisation for PTCA [44. Malenka DJ, O’Rourke D, Miller MA, Hearne MJ, Shubrooks S, Kellett MA, Jr., Robb JF, O’Meara JR, VerLee P, Bradley WA, Wennberg D, Ryan T, Jr., Vaitkus PT, Hettleman B, Watkins MW, McGrath PD and O’Connor GT. Cause of in-hospital death in 12,232 consecutive patients undergoing percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. The Northern New England Cardiovascular Disease Study Group. Am Heart J. 1999. ]. Venous thromboembolism (VTE) shares risk factors with atherothrombosis [55. Pesavento R, Piovella C and Prandoni P. Heart disease in patients with pulmonary embolism. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2010. ]. Prevention of arterial vascular events with rosuvastatin in the Jupiter trial [66. Ridker PM, Danielson E, Fonseca FA, Genest J, Gotto AM, Jr., Kastelein JJ, Koenig W, Libby P, Lorenzatti AJ, MacFadyen JG, Nordestgaard BG, Shepherd J, Willerson JT and Glynn RJ. Rosuvastatin to prevent vascular events in men and women with elevated C-reactive protein. N Engl J Med. 2008. ] prevented arterial as much as venous thrombotic events [77. Glynn RJ, Danielson E, Fonseca FA, Genest J, Gotto AM, Jr., Kastelein JJ, Koenig W, Libby P, Lorenzatti AJ, MacFadyen JG, Nordestgaard BG, Shepherd J, Willerson JT and Ridker PM. A randomized trial of rosuvastatin in the prevention of venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2009. ]. Within two years, treatment with rosuvastatin prevented 99 acute myocardial infarctions, 97 strokes, but also 94 symptomatic cases of deep venous thrombosis/pulmonary embolism.

PE is a challenging diagnosis which may be missed because of variable symptoms. Early diagnosis is needed because immediate treatment is highly effective.

Depending on the clinical presentation, initial therapy is primarily aimed either at life-saving restoration of flow through occluded pulmonary arteries or at the prevention of early recurrences. Immediate risk stratification is essential ( Figure 1 ).

Both initial treatment and long-term anticoagulation must be justified in each patient by a validated diagnostic strategy.

Failure to resolve acute pulmonary thromboemboli is a potential explanation for chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH). This condition appears to be one of the more common subsets of pulmonary hypertension [88. Lang IM. Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension--not so rare after all. N Engl J Med. 2004. ], yet hard to diagnose. Valuable epidemiological data will be derived from the ongoing European CTEPH Registry (https://www.cteph-association.org/).

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Pulmonary embolism (PE) and deep venous thrombosis (DVT) are two closely related clinical presentations of venous thromboembolism (VTE). About 50% of patients with proximal DVT subsequently develop mostly asymptomatic PE [99. Moser KM, Fedullo PF, LitteJohn JK and Crawford R. Frequent asymptomatic pulmonary embolism in patients with deep venous thrombosis. JAMA. 1994. ]. Conversely, the complication of a DVT of the lower limbs accounts for approximately 70% of PEs [1010. Dalen JE. Pulmonary embolism: what have we learned since Virchow? Natural history, pathophysiology, and diagnosis. Chest. 2002. , 1111. Kearon C. Natural history of venous thromboembolism. Circulation. 2003. ]. VTE is the third most common cardiovascular disease after acute ischaemic syndromes and stroke and is associated with substantial morbidity and mortality [66. Ridker PM, Danielson E, Fonseca FA, Genest J, Gotto AM, Jr., Kastelein JJ, Koenig W, Libby P, Lorenzatti AJ, MacFadyen JG, Nordestgaard BG, Shepherd J, Willerson JT and Glynn RJ. Rosuvastatin to prevent vascular events in men and women with elevated C-reactive protein. N Engl J Med. 2008. ]. In the USA, the overall age and sex-adjusted incidence of VTE is 77.6 per 100,000 [1212. Heit JA. The epidemiology of venous thromboembolism in the community: implications for prevention and management. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2006. ]. The incidence of PE among hospitalised patients is about 0.4% [1313. Stein PD, Beemath A and Olson RE. Trends in the incidence of pulmonary embolism and deep venous thrombosis in hospitalized patients. Am J Cardiol. 2005. ]. VTE is predominantly a disease of older age. The incidence rates increase exponentially with age in both men and women [11. Silverstein MD, Heit JA, Mohr DN, Petterson TM, O’Fallon WM and Melton LJ, 3rd. Trends in the incidence of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a 25-year population-based study. Arch Intern Med. 1998. ] [1414. Cushman M, Tsai AW, White RH, Heckbert SR, Rosamond WD, Enright P and Folsom AR. Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in two cohorts: the longitudinal investigation of thromboembolism etiology. Am J Med. 2004. ].

The crude mortality rate for acute PE at three months is about 15%, which is higher than that for myocardial infarction [1515. Goldhaber SZ, Visani L and De Rosa M. Acute pulmonary embolism: clinical outcomes in the International Cooperative Pulmonary Embolism Registry (ICOPER). Lancet. 1999. ]. One-year mortality after a VTE is 17% to 22%[1616. Naess IA, Christiansen SC, Romundstad P, Cannegieter SC, Rosendaal FR and Hammerstrom J. Incidence and mortality of venous thrombosis: a population-based study. J Thromb Haemost. 2007. , 1717. Prandoni P, Lensing AW, Cogo A, Cuppini S, Villalta S, Carta M, Cattelan AM, Polistena P, Bernardi E and Prins MH. The long-term clinical course of acute deep venous thrombosis. Ann Intern Med. 1996. ] , while two-year mortality is 20% to 25% [1717. Prandoni P, Lensing AW, Cogo A, Cuppini S, Villalta S, Carta M, Cattelan AM, Polistena P, Bernardi E and Prins MH. The long-term clinical course of acute deep venous thrombosis. Ann Intern Med. 1996. , 1818. Anderson FA, Jr., Wheeler HB, Goldberg RJ, Hosmer DW, Patwardhan NA, Jovanovic B, Forcier A and Dalen JE. A population-based perspective of the hospital incidence and case-fatality rates of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. The Worcester DVT Study. Arch Intern Med. 1991. ] . Murin et al reported a 6-month fatality rate of 10.5% among patients with DVT and 14.7% among those with PE [1919. Murin S, Romano PS and White RH. Comparison of outcomes after hospitalization for deep venous thrombosis or pulmonary embolism. Thromb Haemost. 2002. ]. Sudden death occurs in almost 25% of patients with PE [1212. Heit JA. The epidemiology of venous thromboembolism in the community: implications for prevention and management. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2006. ]. Right heart failure resulting in cardiovascular collapse is the most common reason for death [1212. Heit JA. The epidemiology of venous thromboembolism in the community: implications for prevention and management. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2006. ]. It has been shown that patients diagnosed with PE during hospitalisation for another condition had a higher case-fatality rate (32.5%) than those admitted for PE. 11.6% of patients died during their initial hospitalisation, 5% of those with DVT and 23% of those with PE [1818. Anderson FA, Jr., Wheeler HB, Goldberg RJ, Hosmer DW, Patwardhan NA, Jovanovic B, Forcier A and Dalen JE. A population-based perspective of the hospital incidence and case-fatality rates of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. The Worcester DVT Study. Arch Intern Med. 1991. ] .

Increased mortality risk in patients with PE is associated with systolic arterial hypotension, congestive heart failure, cancer, tachypnoea, poor right-ventricular function by echocardiography, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and age >70 years [1515. Goldhaber SZ, Visani L and De Rosa M. Acute pulmonary embolism: clinical outcomes in the International Cooperative Pulmonary Embolism Registry (ICOPER). Lancet. 1999. ].

A large epidemiological study reported that 59% of incident VTE cases could be attributed to immobilisation or nursing home residence, 18% to cancer and 12% to trauma. Congestive heart failure and prior central venous catheter or pacemaker placement were responsible for 10% and 9% of VTE cases respectively. In summary, recognised clinical risk factors are responsible for ~ 75% of VTE cases, while ~ 25% are idiopathic [2020. Heit JA, O’Fallon WM, Petterson TM, Lohse CM, Silverstein MD, Mohr DN and Melton LJ, 3rd. Relative impact of risk factors for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a population-based study. Arch Intern Med. 2002. ].

PE has a relatively high recurrence rate. Analyses of the California Patients Discharge Data Set [1919. Murin S, Romano PS and White RH. Comparison of outcomes after hospitalization for deep venous thrombosis or pulmonary embolism. Thromb Haemost. 2002. ] revealed that the 6-month recurrence rate of VTE was 6.4% in the cohort of patients hospitalised for DVT and 5.8% in the cohort initially hospitalised for PE. In a prospective cohort study of 738 patients with DVT, reported recurrence rates of VTE were 7.0% at 1 year and 22.0% at 5 years [2121. Hansson PO, Sorbo J and Eriksson H. Recurrent venous thromboembolism after deep vein thrombosis: incidence and risk factors. Arch Intern Med. 2000. ]. Survivors of acute PE have an increased risk of CTEPH [2222. Fanikos J, Piazza G, Zayaruzny M and Goldhaber SZ. Long-term complications of medical patients with hospital-acquired venous thromboembolism. Thromb Haemost. 2009. ].

PATHOPHYSIOLOGICAL MECHANISMS OF PULMONARY EMBOLISM

The clinical manifestation of VTE can be subdivided into DVT and PE [2323. Tapson VF. Acute pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2008. ]. In most cases, PE is a severe complication of DVT of the legs, and ranges from asymptomatic, incidentally discovered thromboemboli to massive embolism that results in obstruction of the pulmonary vasculature. Thrombi in the leg may form at any point along the vein wall and any venous bed can be involved. The vast majority of venous thrombi are asymptomatic, and form on the valve pockets of deep veins in the calf [2424. Kakkar VV, Howe CT, Flanc C and Clarke MB. Natural history of postoperative deep-vein thrombosis. Lancet. 1969. ]. However, these thrombi can extend into the proximal veins, including and above the popliteal veins [2525. Cotton LT and Clark C. Anatomical Localization of Venous Thrombosis. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1965. ], become symptomatic and prone to embolisation. In about 80% of patients with PE, signs of a DVT are documented [2626. Sandler DA and Martin JF. Autopsy proven pulmonary embolism in hospital patients: are we detecting enough deep vein thrombosis?. J R Soc Med. 1989. ]. Conversely, up to 50% of patients will develop a PE in the setting of DVT. If embolisation does not occur, the thrombus within the vein can be partially or completely resolved via recanalisation, organisation, and lysis.

PE as a complication of percutaneous coronary intervention

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is associated with various in-hospital complications including death, myocardial infarction, emergency coronary artery bypass grafting, stroke, contrast-induced nephropathy, and vascular access-site complications [2727. Smith SC, Jr., Dove JT, Jacobs AK, Kennedy JW, Kereiakes D, Kern MJ, Kuntz RE, Popma JJ, Schaff HV, Williams DO, Gibbons RJ, Alpert JP, Eagle KA, Faxon DP, Fuster V, Gardner TJ, Gregoratos G and Russell RO. ACC/AHA guidelines for percutaneous coronary intervention (revision of the 1993 PTCA guidelines)-executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines (Committee to revise the 1993 guidelines for percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty) endorsed by the Society for Cardiac Angiography and Interventions. Circulation. 2001. ]. PE is a relatively common cardiovascular emergency, yet it is a rare but significant complication of PCI, occurring in 1.7% of cases [44. Malenka DJ, O’Rourke D, Miller MA, Hearne MJ, Shubrooks S, Kellett MA, Jr., Robb JF, O’Meara JR, VerLee P, Bradley WA, Wennberg D, Ryan T, Jr., Vaitkus PT, Hettleman B, Watkins MW, McGrath PD and O’Connor GT. Cause of in-hospital death in 12,232 consecutive patients undergoing percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. The Northern New England Cardiovascular Disease Study Group. Am Heart J. 1999. ]. The mortality related to PE in this PCI population is 0.016% [44. Malenka DJ, O’Rourke D, Miller MA, Hearne MJ, Shubrooks S, Kellett MA, Jr., Robb JF, O’Meara JR, VerLee P, Bradley WA, Wennberg D, Ryan T, Jr., Vaitkus PT, Hettleman B, Watkins MW, McGrath PD and O’Connor GT. Cause of in-hospital death in 12,232 consecutive patients undergoing percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. The Northern New England Cardiovascular Disease Study Group. Am Heart J. 1999. ]. No data exists regarding more recent experience after introduction of femoral vascular closure devices, which have reduced the time to ambulation.

Under dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel, PE was observed in only 0.026% of patients within 6 months [2828. Serebruany V, Pokov I, Kuliczkowski W, Vahabi J and Atar D. Incidence and causes of new-onset dyspnea in 3,719 patients treated with clopidogrel and aspirin combination after coronary stenting. Thromb Haemost. 2008. ]. Data from the PEP study and from the Anti-Platelet Trialists’ systematic review shows that aspirin significantly reduces the risk of VTE in surgical patients. However, there is no general evidence that aspirin is a drug that is useful for the prevention of VTE in any patient group [2929. O’Brien J, Duncan H, Kirsh G, Allen V, King P, Hargraves R, Mendes L, Perera T, Catto P, Schofield S, Ploschke H, Hefner T, Churchland M, Woolnough S, Wuttke R, Manning M, Jeffries T, Hensley L, Bath P, Bainbridge D, Guinane F, McMahon L, Zavattaro D, Wilson D, Blake K, Morton J, Sharman D, Locke R, Ghabrial J, McNeil S, Rehfisch P, van der Merwe S, Einoder B, Douglas D, Ashwell J, Morrissey A, Brown A, Simm R, Fisch G, Crawford W, Everding T, Tanham D, Hooper J, Aldana C, Goldwasser M, Mibus M, Rowden N, Mills J, Johnson P, Stilwell J, Williams R, Stevenson T, Zwar J, Bauze R, Nyunt B, Russell R, Day G, Cameron M, Clements P, Beck T, Ellis A, Phipps S, Quaill W, Skirving A, McGuiness M, Gray P, Rankin J, Wood D, Senior J, Courtenay B, Green M, Harris I, Rush J, Kilgour M, Davies J, Newcombe J, Lewis C, Leitl S, Chilcott R, Pianta R, Aguila A, Hawe C, Nade S, Smith M, Robertson P, Rothwell A, May S, Williams S, Rothwell A, Shamy S, Martin G, Steele V, Jeffery K, Kelman I, McKillan J, Dayaram P, Culling J, Lawson D, Winfield P, Kuzel R, Milburn C, Palmer N, Pitts A, Lamb G, Prodan L, Gray H, Walker K, Smith K, Newton C, Atkinson D, Fail B, Panting A, Menzies J, Watkiss A, Robertson P, Outhred J, Clay D, Lander R, Fou R, Clarke DS, Murrell T, Rolleston B, Clarke DS, Keyworth S, Medlicott P, Woods T, Dawe C, Waldron R, Taine W, Le Roy L, Smith A, Cowley G, Campbell C, Maxwell R, Elvy M, Thurston A, Newth S, Cousins L, Sanderson M, MacMillan C, Golele R, Walters J, Kruger S, Ramsden T, Joseph H, Gantz D, Steyn S, Hadjichristofis S, Nojoko L, Snowdowne R, Botha M, Knebel R, Sernbo I, Ferris B, Tello E, Nevelos A, Dunn C, Warwick D, Sudhakar J, Tuite JD, Francis J, Wallace ME, Jordan A, Baird P, Fowler W, Ainscow DAP, Harrison A, Butler-Manuel A, Palmer N, Broome G, Swailes P, Stahl TJ, Randall AM, Forester AJ, Hucker J, Redden J, Logan L, Howard PW, Brownlee D, Angus P, Boyce A, Porter BB, Arbid M, Youll J, Ogden AS, MacDowell C, Beverly M, Ramdeholl P, Nelson I, Howlett I, Warwick D, Weeber A, Peacock A, Hubbard MJS, Flanagan M, Crawshaw C, Kinninmonth A, Campbell T, Tibrewal S, Lennox CME, Clifford I, Gillham N, Hunt M, Bulstrode C, Handley R, Iyer V, Lawton J, Robbins J, Harper WM, Davison J, Hope P, Smallbones K, Jones W, Ratnam KR, Upton J, Hirst P, Knox S, Sadique T, Khan M, Umar M, Anderson J, Frank J, Briggs P, Sanderson P, McBride D, Leese K, Bayliss NC, El-Deen M, Banan H, Williams S, Parker MJ, Minhas H, Best A, Blakeway C, Salter T, Foy MA, Pollitt A, Blayney JDM, Davis S, Parnell E, Ko C, Grover ML, Howells S, Williams D, Saunders C, Brenkel I, Mani G, Grizzle M, Henderson A, Board T, Chadwick CJ, Overton M, Hodkinson S, Macdonald DA, Lewis V, McDonald RJM, Adamson J, Bradley J, Hodgson E, Plewes JL, Clarke D, Hullin M, Smith J, Lemon GJ, Greatrex K, Miles C, Bannister G, Dare J, Carden DG, Aughton J, Stirrat A, Fishburn J, Ebizie AO, Mason M, Irvine G, Facey T, Spratt C, Briggs P, Kanagavel N, Gerrard T, Reissis N, Tzanetos P, Stefanotti M, Greiss M, Wright V, Rahmaty A, Archer J, Bedford A, Taylor D, Griffith M, Evans J, Heron K, Livingstone B, O’Dwyer K, Wheatley D, Lemon GJ, Miles C, Campbell P, Dixon P, McSweeney L, Shanahan MDG, Griffith I, MacMahon S, Rodgers A, Collins R, Prentice C, Gray H, MacMahon S, Norton R, Ockleford P, Rodgers A, Rutland M, Collins R, Prentice C, Dickinson J, Gregg P, Macdonald D, Mollan RAB, Douglas J, Beaumont D, Broad J, Clark T, Henderson M, McCulloch A, Neal B, Prasad R, Walker N, Wood M, Beighton A, Bell P, Farrell B, Murch K, Sharpe N, Gordon G, Doughty R, Ratnasabapathy Y, Danesh J, Sleight P, Peto R, Simes J, Keech A, Rodgers A, MacMahon S, Collins R, Prentice C and Tri PEP. Prevention of pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis with low dose aspirin: Pulmonary Embolism Prevention (PEP) trial. Lancet. 2000. , 3030. Watson HG and Chee YL. Aspirin and other antiplatelet drugs in the prevention of venous thromboembolism. Blood Rev. 2008. ].

Venous thromboembolism and atherothrombosis

Atherothrombosis and VTE are associated [3131. Becattini C, Vedovati MC, Ageno W, Dentali F and Agnelli G. Incidence of arterial cardiovascular events after venous thromboembolism: a systematic review and a meta-analysis. J Thromb Haemost. 2010. ], and share risk factors such as obesity, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, diabetes, and smoking [3232. Ageno W, Becattini C, Brighton T, Selby R and Kamphuisen PW. Cardiovascular risk factors and venous thromboembolism: a meta-analysis. Circulation. 2008. , 3333. Goon PK and Lip GY. Arterial disease and venous thromboembolism: a modern paradigm?. Thromb Haemost. 2006. , 3434. . Holst AG, Jensen G and Prescott E. Risk factors for venous thromboembolism: results from the Copenhagen City Heart Study.

Circulation]. Inflammation, systemic and local hypercoagulability, and endothelial injury play crucial roles in the development of both atherothrombosis and VTE [3333. Goon PK and Lip GY. Arterial disease and venous thromboembolism: a modern paradigm?. Thromb Haemost. 2006. , 3535. Piazza G and Goldhaber SZ. Venous thromboembolism and atherothrombosis: an integrated approach. Circulation. 2010. ]]. Patients with acute coronary syndromes or stroke have an increased susceptibility of VTE [3636. Piazza G, Fanikos J, Zayaruzny M and Goldhaber SZ. Venous thromboembolic events in hospitalised medical patients. Thromb Haemost. 2009. , 3737. Sorensen HT, Horvath-Puho E, Lash TL, Christiansen CF, Pesavento R, Pedersen L, Baron JA and Prandoni P. Heart disease may be a risk factor for pulmonary embolism without peripheral deep venous thrombosis. Circulation. 2011. ]. Additionally, an association between atherosclerotic disease and spontaneous venous thrombosis has been demonstrated [3838. Prandoni P, Bilora F, Marchiori A, Bernardi E, Petrobelli F, Lensing AW, Prins MH and Girolami A. An association between atherosclerosis and venous thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 2003. ]. Subsequent studies detected a drastically increased cardiovascular risk in patients with a prior history of VTE compared with those without such a history [3939. Becattini C, Agnelli G, Prandoni P, Silingardi M, Salvi R, Taliani MR, Poggio R, Imberti D, Ageno W, Pogliani E, Porro F and Casazza F. A prospective study on cardiovascular events after acute pulmonary embolism. Eur Heart J. 2005. , 4040. Klok FA, Mos IC, Broek L, Tamsma JT, Rosendaal FR, de Roos A and Huisman MV. Risk of arterial cardiovascular events in patients after pulmonary embolism. Blood. 2009. , 4141. Sorensen HT, Horvath-Puho E, Pedersen L, Baron JA and Prandoni P. Venous thromboembolism and subsequent hospitalisation due to acute arterial cardiovascular events: a 20-year cohort study. Lancet. 2007. , 4242. Spencer FA, Ginsberg JS, Chong A and Alter DA. The relationship between unprovoked venous thromboembolism, age, and acute myocardial infarction. J Thromb Haemost. 2008. ].

The prognostic value of C-reactive protein, a sensitive systemic marker of inflammation for cardiovascular events [4343. Koenig W, Sund M, Frohlich M, Fischer HG, Lowel H, Doring A, Hutchinson WL and Pepys MB. C-Reactive protein, a sensitive marker of inflammation, predicts future risk of coronary heart disease in initially healthy middle-aged men: results from the MONICA (Monitoring Trends and Determinants in Cardiovascular Disease) Augsburg Cohort Study, 1984 to 1992. Circulation. 1999. , 4444. Ridker PM, Cushman M, Stampfer MJ, Tracy RP and Hennekens CH. Inflammation, aspirin, and the risk of cardiovascular disease in apparently healthy men. N Engl J Med. 1997. ] and VTE [4545. Folsom AR, Lutsey PL, Astor BC and Cushman M. C-reactive protein and venous thromboembolism. A prospective investigation in the ARIC cohort. Thromb Haemost. 2009. ], has been investigated. Rosuvastatin prevented arterial events in a population with elevated high-sensitivity C-reactive protein levels [4646. Albert MA, Danielson E, Rifai N and Ridker PM. Effect of statin therapy on C-reactive protein levels: the pravastatin inflammation/CRP evaluation (PRINCE): a randomized trial and cohort study. JAMA. 2001. ] in the Jupiter trial (Justification for the Use of statins in Prevention: an Intervention Trial Evaluating Rosuvastatin) [66. Ridker PM, Danielson E, Fonseca FA, Genest J, Gotto AM, Jr., Kastelein JJ, Koenig W, Libby P, Lorenzatti AJ, MacFadyen JG, Nordestgaard BG, Shepherd J, Willerson JT and Glynn RJ. Rosuvastatin to prevent vascular events in men and women with elevated C-reactive protein. N Engl J Med. 2008. ], and simultaneously prevented symptomatic venous thrombotic events [77. Glynn RJ, Danielson E, Fonseca FA, Genest J, Gotto AM, Jr., Kastelein JJ, Koenig W, Libby P, Lorenzatti AJ, MacFadyen JG, Nordestgaard BG, Shepherd J, Willerson JT and Ridker PM. A randomized trial of rosuvastatin in the prevention of venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2009. ].

Hypercoagulability plays an important role in the development of VTE as well as in atherothrombosis. An increased risk of both conditions has been described in women on oestrogen and progesterone therapy and in patients with lupus anticoagulant [4747. Rosendaal FR, Helmerhorst FM and Vandenbroucke JP. Female hormones and thrombosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002. ]. Endothelial injury as a trigger for atherothrombosis and DVT has been well established [4848. Joffe HV, Kucher N, Tapson VF and Goldhaber SZ. Upper-extremity deep vein thrombosis: a prospective registry of 592 patients. Circulation. 2004. , 4949. Libby P, Ridker PM and Maseri A. Inflammation and atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2002. , 5050. van Stralen KJ, Rosendaal FR and Doggen CJ. Minor injuries as a risk factor for venous thrombosis. Arch Intern Med. 2008. ].

RISK FACTORS FOR PE

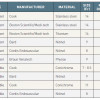

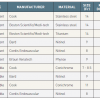

Although PE can occur in patients without any known risk factor, certain predisposing factors are associated with an increased risk of VTE. The International Cooperative Pulmonary Embolism Registry (ICOPER) showed that less than a quarter of PE were idiopathic or unprovoked [1515. Goldhaber SZ, Visani L and De Rosa M. Acute pulmonary embolism: clinical outcomes in the International Cooperative Pulmonary Embolism Registry (ICOPER). Lancet. 1999. ]. In 1856, Virchow first proposed a triad of factors leading to intravascular coagulation, including stasis of blood flow, vascular endothelial damage, and hypercoagulability of blood [5151. Virchow R. Phlogose und Thrombose im Gefässystem. Gesammelte Abhandlungen zur Wissenschaftlichen Medicin. Frankfurt, Germany: Meidinger. 1856. ]. Risk factors for VTE are outlined Table 1. [5252. Konstantinides SV, Torbicki A, Agnelli G, Danchin N, Fitzmaurice D, Galie N, Gibbs JS, Huisman MV, Humbert M, Kucher N, Lang I, Lankeit M, Lekakis J, Maack C, Mayer E, Meneveau N, Perrier A, Pruszczyk P, Rasmussen LH, Schindler TH, Svitil P, Vonk Noordegraaf A, Zamorano JL, Zompatori M, Task Force for the D and Management of Acute Pulmonary Embolism of the European Society of C. 2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism. Eur Heart J. 2014.

Latest European guidelines on acute pulmonary embolism, 5353. Rosendaal FR. Venous thrombosis: a multicausal disease. Lancet. 1999. ]. The incidence of VTE correlates with increasing age for both idiopathic and secondary PE [5454. Oger E. Incidence of venous thromboembolism: a community-based study in Western France. EPI-GETBP Study Group. Groupe d’Etude de la Thrombose de Bretagne Occidentale. Thromb Haemost. 2000. ]. Approximately 65% of patients with PE are aged 60 years or older. The incidence of PE is eight times higher in patients over 80 compared with those under 50 years of age [5555. Hansson PO, Welin L, Tibblin G and Eriksson H. Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in the general population. ’The Study of Men Born in 1913’. Arch Intern Med. 1997. ]. Total risk depends on the number of predisposing factors [5656. Anderson FA, Jr. and Spencer FA. Risk factors for venous thromboembolism. Circulation. 2003. ].

Two large meta-analyses have investigated vascular access-related complications in patients undergoing percutaneous transfemoral coronary procedures [5757. Koreny M, Riedmuller E, Nikfardjam M, Siostrzonek P and Mullner M. Arterial puncture closing devices compared with standard manual compression after cardiac catheterization: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004. , 5858. Nikolsky E, Mehran R, Halkin A, Aymong ED, Mintz GS, Lasic Z, Negoita M, Fahy M, Krieger S, Moussa I, Moses JW, Stone GW, Leon MB, Pocock SJ and Dangas G. Vascular complications associated with arteriotomy closure devices in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary procedures: a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004. ]. In both studies, venous thromboembolic events were not included in the reporting of vascular access-related complications. Whether the condition is under-reported, or VTE as a complication of coronary angiography has in fact decreased since the general implementation of arterial puncture site closing devices shortening bed rest after coronary angiography, is unknown. In addition, the improvement of patient care and the implementation of dual antiplatelet therapy and continued anticoagulation might be responsible for the apparent reduction of VTE after PCI.

RISK STRATIFICATION

PE is a potentially life-threatening disorder. The rate of recurrent and potentially fatal events may be significantly reduced by treatment with either unfractionated heparin (UFH), low-molecular weight heparin (LMWH), or fondaparinux [2323. Tapson VF. Acute pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2008. ]. Risk stratification of patients with PE helps to distinguish between those candidates at low risk who are appropriate for a therapy outside the hospital setting and those individuals at higher risk who require hospitalisation.

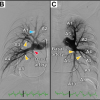

According to the ESC guidelines, the severity of PE is stratified into high (>15%), intermediate (3% to 15%) and low risk (<1%) of PE-related early death (in-hospital or 30-day mortality) as depicted in Figure 1A [5252. Konstantinides SV, Torbicki A, Agnelli G, Danchin N, Fitzmaurice D, Galie N, Gibbs JS, Huisman MV, Humbert M, Kucher N, Lang I, Lankeit M, Lekakis J, Maack C, Mayer E, Meneveau N, Perrier A, Pruszczyk P, Rasmussen LH, Schindler TH, Svitil P, Vonk Noordegraaf A, Zamorano JL, Zompatori M, Task Force for the D and Management of Acute Pulmonary Embolism of the European Society of C. 2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism. Eur Heart J. 2014.

Latest European guidelines on acute pulmonary embolism]. The presence of hypotension or shock at the time of PE diagnosis is the most powerful predictor of early death, independent of further risk markers [1515. Goldhaber SZ, Visani L and De Rosa M. Acute pulmonary embolism: clinical outcomes in the International Cooperative Pulmonary Embolism Registry (ICOPER). Lancet. 1999. , 5959. Kucher N, Rossi E, De Rosa M and Goldhaber SZ. Massive pulmonary embolism. Circulation. 2006. ]. Consequently, haemodynamically unstable individuals with suspected PE should immediately be classified as high-risk patients and require an emergency diagnostics and treatment. All other patients are thus automatically identified as non-high-risk patients and should be further stratified into intermediate and low risk patients after PE has been confirmed. This stratification may critically influence treatment and the duration of hospitalisation and should be based on the Pulmonary Embolism Severity Index (PESI) [6060. Aujesky D, Obrosky DS, Stone RA, Auble TE, Perrier A, Cornuz J, Roy PM and Fine MJ. Derivation and validation of a prognostic model for pulmonary embolism. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005. ] or simplified PESI (sPESI) [6161. Jimenez D, Aujesky D, Moores L, Gomez V, Lobo JL, Uresandi F, Otero R, Monreal M, Muriel A and Yusen RD. Simplification of the pulmonary embolism severity index for prognostication in patients with acute symptomatic pulmonary embolism. Arch Intern Med. 2010. ] ( Figure 1 [B] ). The PESI, comprising 11 routinely available clinical parameters, represents a well-established approach to estimate 30-day mortality for patients with acute PE. This model can be used to give clinicians a beside risk assessment tool for patients with PE, without any need for imaging studies such as echocardiography or laboratory tests. To reduce the technical complexity of the original prediction rule, a simplified version of the PESI score has been developed, which is easily calculated at bedside ( Figure 1 [B] ) [6161. Jimenez D, Aujesky D, Moores L, Gomez V, Lobo JL, Uresandi F, Otero R, Monreal M, Muriel A and Yusen RD. Simplification of the pulmonary embolism severity index for prognostication in patients with acute symptomatic pulmonary embolism. Arch Intern Med. 2010. ]. Recent data suggest that both PESI and the sPESI predict 30-day mortality after acute symptomatic PE.

Patients at intermediate risk are further classified into intermediate-high and intermediate-low risk patients according to signs of right ventricular (RV) dysfunction based on imaging and/or biomarkers. Defined markers of RV dysfunction are RV dilatation, hypokinesis or pressure overload on echocardiography, RV dilatation on spiral computed tomography, and elevated right heart pressures at right-heart catheterisation. N-terminal (NT)-proBNP represents the best validated biomarker for severity of haemodynamic compromise and RV dysfunction in the setting of PE [6262. Henzler T, Roeger S, Meyer M, Schoepf UJ, Nance JW, Jr., Haghi D, Kaminski WE, Neumaier M, Schoenberg SO and Fink C. Pulmonary embolism: CT signs and cardiac biomarkers for predicting right ventricular dysfunction. Eur Respir J. 2012. ]. NT-proBNP plasma levels of 600 pg/mL were found as the optimal cut-off value for identifying patients at increased risk [6363. Lankeit M, Jimenez D, Kostrubiec M, Dellas C, Kuhnert K, Hasenfuss G, Pruszczyk P and Konstantinides S. Validation of N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide cut-off values for risk stratification of pulmonary embolism. Eur Respir J. 2014. ]. Troponin T or I testing can detect myocardial injury and positive results identify patients at higher risk. The development of high-sensitive assays has further improved the prognostic value of troponin T [6464. Lankeit M, Friesen D, Aschoff J, Dellas C, Hasenfuss G, Katus H, Konstantinides S and Giannitsis E. Highly sensitive troponin T assay in normotensive patients with acute pulmonary embolism. Eur Heart J. 2010. ].

The presence of concomitant DVT in patients with acute symptomatic PE is an independent predictor of death in the three months following the diagnosis [6161. Jimenez D, Aujesky D, Moores L, Gomez V, Lobo JL, Uresandi F, Otero R, Monreal M, Muriel A and Yusen RD. Simplification of the pulmonary embolism severity index for prognostication in patients with acute symptomatic pulmonary embolism. Arch Intern Med. 2010. ]. Therefore, bilateral lower extremity compression ultrasonography should assist with risk stratification of patients with acute PE. Venous ultrasound imaging of the entire deep vein system is highly specific (about 95%) and sensitive (over 90%) for the diagnosis of DVT [6565. Kearon C, Ginsberg JS and Hirsh J. The role of venous ultrasonography in the diagnosis of suspected deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Ann Intern Med. 1998. , 6666. Perrier A and Bounameaux H. Ultrasonography of leg veins in patients suspected of having pulmonary embolism. Ann Intern Med. 1998. , 6767. Wells PS. Integrated strategies for the diagnosis of venous thromboembolism. J Thromb Haemost. 2007. ].

DIAGNOSTIC STRATEGIES

Due to the large variety and low specificity of symptoms, the diagnosis of PE is challenging. Chest computed tomography (CT) is regarded as highly sensitive and specific test for PE [6868. Stein PD, Beemath A, Kayali F, Skaf E, Sanchez J and Olson RE. Multidetector computed tomography for the diagnosis of coronary artery disease: a systematic review. Am J Med. 2006. ]. The key to the diagnosis of PE is a high index of clinical suspicion. In order to avoid unnecessary exposure to radiation and contrast agent, without overlooking the condition, a sophisticated diagnostic algorithm has been established [5252. Konstantinides SV, Torbicki A, Agnelli G, Danchin N, Fitzmaurice D, Galie N, Gibbs JS, Huisman MV, Humbert M, Kucher N, Lang I, Lankeit M, Lekakis J, Maack C, Mayer E, Meneveau N, Perrier A, Pruszczyk P, Rasmussen LH, Schindler TH, Svitil P, Vonk Noordegraaf A, Zamorano JL, Zompatori M, Task Force for the D and Management of Acute Pulmonary Embolism of the European Society of C. 2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism. Eur Heart J. 2014.

Latest European guidelines on acute pulmonary embolism].

Clinical signs and symptoms

The clinical presentation of patients with PE is highly variable. Frequently reported symptoms include dyspnoea, pleuritic and substernal chest pain, palpitations, cough, seizures, faints and haemoptysis. Patients with high thrombus burden can present with circulatory collapse, mental status changes, syncope and arrhythmias [6969. Aujesky D, Roy PM, Le Manach CP, Verschuren F, Meyer G, Obrosky DS, Stone RA, Cornuz J and Fine MJ. Validation of a model to predict adverse outcomes in patients with pulmonary embolism. Eur Heart J. 2006. , 7070. Stein PD and Henry JW. Clinical characteristics of patients with acute pulmonary embolism stratified according to their presenting syndromes. Chest. 1997. ] . Clinical signs include tachypnoea, tachycardia, signs of DVT (leg pain, warmth, or swelling), fever and cyanosis.

Differential diagnosis of chest pain

Acute chest pain represents one of the most common diagnostic challenges in emergency medicine, accounting for approximately 8% to 10% of the 119 million emergency department visits yearly in the USA [7171. Pitts SR, Niska RW, Xu J and Burt CW. National hospital ambulatory medical care survey: 2006 emergency department summary. In: Services UDoHaH, editor. ; 2006. ]. The differential diagnosis ranges from non-serious musculoskeletal aetiologies to life-threatening cardiac disease. In one large study [7272. Pope JH, Aufderheide TP, Ruthazer R, Woolard RH, Feldman JA, Beshansky JR, Griffith JL and Selker HP. Missed diagnoses of acute cardiac ischemia in the emergency department. N Engl J Med. 2000. ] of patients attending the emergency department with chest pain, 8% were diagnosed with AMI, 9% with unstable angina, 6% with stable angina, 21% had non-ischaemic cardiac problems, and at least 2% of patients with AMI were discharged in error. However, more than 50% of patients with acute chest pain had non-cardiac problems, such as aortic dissection or PE, which may mimic coronary syndromes [7373. Erhardt L, Herlitz J, Bossaert L, Halinen M, Keltai M, Koster R, Marcassa C, Quinn T and van Weert H. Task force on the management of chest pain. Eur Heart J. 2002. ]. Approximately 0.5% of patients who attend emergency departments with suspicion of acute coronary syndrome have a PE [7373. Erhardt L, Herlitz J, Bossaert L, Halinen M, Keltai M, Koster R, Marcassa C, Quinn T and van Weert H. Task force on the management of chest pain. Eur Heart J. 2002. ]. The underlying cause of chest pain varies depending on whether a patient is seen by a general practitioner or at the emergency department. In general practices nearly 50% of patients with chest pain have musculoskeletal pain, whereas in the emergency department 45% have cardiac problems [7373. Erhardt L, Herlitz J, Bossaert L, Halinen M, Keltai M, Koster R, Marcassa C, Quinn T and van Weert H. Task force on the management of chest pain. Eur Heart J. 2002. , 7474. Herlitz J, Bang A, Isaksson L and Karlsson T. Outcome for patients who call for an ambulance for chest pain in relation to the dispatcher’s initial suspicion of acute myocardial infarction. Eur J Emerg Med. 1995. , 7575. Klinkman MS, Stevens D and Gorenflo DW. Episodes of care for chest pain: a preliminary report from MIRNET. Michigan Research Network. J Fam Pract. 1994. , 7676. Svavarsdóttir A, Jónasson M, Gudmundsson G and Fjeldsted K. Chest pain in family practice. Diagnosis and long-term outcome in a community setting. Can Fam Physician 1996. ] . However, even in general practices, PE was identified in 3% of patients with thoracic pain [7676. Svavarsdóttir A, Jónasson M, Gudmundsson G and Fjeldsted K. Chest pain in family practice. Diagnosis and long-term outcome in a community setting. Can Fam Physician 1996. ]. About 3% of patients admitted to a coronary care unit with acute chest pain suffered from PE [7676. Svavarsdóttir A, Jónasson M, Gudmundsson G and Fjeldsted K. Chest pain in family practice. Diagnosis and long-term outcome in a community setting. Can Fam Physician 1996. ]. The enhancement of patient care by rapid diagnoses is an important health care issue.

Physical examination

The diagnosis for PE begins with a careful clinical examination and determination of risk factors. Decreased breath sounds, wheezing, respiratory crackles, accessory muscle use, increased jugular venous pressure, and a right ventricular heave may be detected by physical examination.

Electrocardiogram

An electrocardiogram (ECG) is routinely performed in patients with chest pain attending the emergency department. The ECG is, however, a poor diagnostic tool for PE. Though the ECG is often abnormal, the findings are neither sensitive nor specific. The greatest use of the ECG in patients with suspected PE is to rule out other potential life-threatening diagnoses that can be more readily diagnosed such as myocardial infarction.

The S1Q3T3 pattern is a typical ECG manifestation of acute right ventricular pressure and volume overload. An S wave in lead I indicates a complete or more often incomplete right bundle-branch block. A Q-wave, mild ST-elevation and an inverted T wave in lead III are repolarisation abnormalities possibly triggered by subendocardial ischaemia of the right ventricle.

Further ECG signs of RV strain are T-wave inversion in leads V1–V4, a QR pattern in lead V1, and incomplete or complete right bundle-branch block [7777. Geibel A, Zehender M, Kasper W, Olschewski M, Klima C and Konstantinides SV. Prognostic value of the ECG on admission in patients with acute major pulmonary embolism. Eur Respir J. 2005. , 7878. Rodger M, Makropoulos D, Turek M, Quevillon J, Raymond F, Rasuli P and Wells PS. Diagnostic value of the electrocardiogram in suspected pulmonary embolism. Am J Cardiol. 2000. ]. These findings may be helpful, particularly when of new onset. Nevertheless, such changes are generally associated with the more severe forms of PE and may be found in right ventricular strain of any cause such as acute bronchospasm, pneumothorax and other acute lung disorders.

Implicit and explicit (prediction) rules

Clinical signs, symptoms and routine laboratory tests do not allow the exclusion or confirmation of acute PE but help to estimate a likelihood of PE [5252. Konstantinides SV, Torbicki A, Agnelli G, Danchin N, Fitzmaurice D, Galie N, Gibbs JS, Huisman MV, Humbert M, Kucher N, Lang I, Lankeit M, Lekakis J, Maack C, Mayer E, Meneveau N, Perrier A, Pruszczyk P, Rasmussen LH, Schindler TH, Svitil P, Vonk Noordegraaf A, Zamorano JL, Zompatori M, Task Force for the D and Management of Acute Pulmonary Embolism of the European Society of C. 2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism. Eur Heart J. 2014.

Latest European guidelines on acute pulmonary embolism]. The assessment of clinical probability of PE is based on a combination of individual symptoms, signs and common tests, either implicitly by the clinician or by the use of prediction rules. Implicit clinical judgement combines the knowledge and experience of the clinician to estimate the likelihood of PE. The value of this assessment has been shown in several large series [7979. Musset D, Parent F, Meyer G, Maitre S, Girard P, Leroyer C, Revel MP, Carette MF, Laurent M, Charbonnier B, Laurent F, Mal H, Nonent M, Lancar R, Grenier P and Simonneau G. Diagnostic strategy for patients with suspected pulmonary embolism: a prospective multicentre outcome study. Lancet. 2002. , 8080. Perrier A. Noninvasive diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. Hosp Pract (Minneap). 1998. ]. The main limitations of implicit judgement are lack of standardisation and the challenge of acquiring sufficient experience.

Therefore, prediction rules have been developed for calculating the probability of clinically suspected PE which are independent of physicians’ implicit judgement and which have demonstrated similar accuracy [8181. Chagnon I, Bounameaux H, Aujesky D, Roy PM, Gourdier AL, Cornuz J, Perneger T and Perrier A. Comparison of two clinical prediction rules and implicit assessment among patients with suspected pulmonary embolism. Am J Med. 2002. ]. Prediction rules calculate the probability of suspected PE from a combination of symptoms and clinical signs. The revised Geneva score [8282. Le Gal G, Righini M, Roy PM, Sanchez O, Aujesky D, Bounameaux H and Perrier A. Prediction of pulmonary embolism in the emergency department: the revised Geneva score. Ann Intern Med. 2006. ] and Wells score [8383. Wells PS, Anderson DR, Rodger M, Ginsberg JS, Kearon C, Gent M, Turpie AG, Bormanis J, Weitz J, Chamberlain M, Bowie D, Barnes D and Hirsh J. Derivation of a simple clinical model to categorize patients probability of pulmonary embolism: increasing the models utility with the SimpliRED D-dimer. Thromb Haemost. 2000. ] represent two established and well validated prediction rules that were further simplified to increase their usefulness in clinical practice ( Table 2 and Table 3 [8484. Gibson NS, Sohne M, Kruip MJ, Tick LW, Gerdes VE, Bossuyt PM, Wells PS, Buller HR and Christopher study i. Further validation and simplification of the Wells clinical decision rule in pulmonary embolism. Thromb Haemost. 2008. , 8585. Klok FA, Mos IC, Nijkeuter M, Righini M, Perrier A, Le Gal G and Huisman MV. Simplification of the revised Geneva score for assessing clinical probability of pulmonary embolism. Arch Intern Med. 2008. ]).

D-dimer

Plasma D-dimer, a degradation product of cross-linked fibrin, is a very sensitive but non-specific marker for VTE. A negative test result is valid to rule out PE in patients with a low or moderate clinical probability [6767. Wells PS. Integrated strategies for the diagnosis of venous thromboembolism. J Thromb Haemost. 2007. ]. However, positive D-dimer tests should be considered with caution because this parameter is susceptible to false positive results. Levels of D-dimer are elevated in many other clinical conditions, such as cancer, inflammation, infection, necrosis, bleeding, dissection of the aorta, pregnancy and hospitalisation per se [8686. Bruinstroop E, van de Ree MA and Huisman MV. The use of D-dimer in specific clinical conditions: a narrative review. Eur J Intern Med. 2009. ]. For this reason, D-dimer is not a useful parameter for confirming PE. The number of patients with suspected PE in whom D-dimer needs to be determined to exclude one PE is between three in the emergency department and ten or above in other conditions [5252. Konstantinides SV, Torbicki A, Agnelli G, Danchin N, Fitzmaurice D, Galie N, Gibbs JS, Huisman MV, Humbert M, Kucher N, Lang I, Lankeit M, Lekakis J, Maack C, Mayer E, Meneveau N, Perrier A, Pruszczyk P, Rasmussen LH, Schindler TH, Svitil P, Vonk Noordegraaf A, Zamorano JL, Zompatori M, Task Force for the D and Management of Acute Pulmonary Embolism of the European Society of C. 2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism. Eur Heart J. 2014.

Latest European guidelines on acute pulmonary embolism]. Physical examination should be performed as the first diagnostic step, prior to considering D-dimer [5252. Konstantinides SV, Torbicki A, Agnelli G, Danchin N, Fitzmaurice D, Galie N, Gibbs JS, Huisman MV, Humbert M, Kucher N, Lang I, Lankeit M, Lekakis J, Maack C, Mayer E, Meneveau N, Perrier A, Pruszczyk P, Rasmussen LH, Schindler TH, Svitil P, Vonk Noordegraaf A, Zamorano JL, Zompatori M, Task Force for the D and Management of Acute Pulmonary Embolism of the European Society of C. 2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism. Eur Heart J. 2014.

Latest European guidelines on acute pulmonary embolism]. It has become evident that the specificity of D-dimer in individuals with suspected PE declines with age [8787. Righini M, Goehring C, Bounameaux H and Perrier A. Effects of age on the performance of common diagnostic tests for pulmonary embolism. Am J Med. 2000. ]. Therefore, an age-adjusted cut-off (patient's age in years × 10 µg/L) has been developed to improve the specificity of D-dimer testing for excluding PE [8888. Douma RA, le Gal G, Sohne M, Righini M, Kamphuisen PW, Perrier A, Kruip MJ, Bounameaux H, Buller HR and Roy PM. Potential of an age adjusted D-dimer cut-off value to improve the exclusion of pulmonary embolism in older patients: a retrospective analysis of three large cohorts. BMJ. 2010. ]. The combination of pretest clinical probability assessment with an age-adjusted D-dimer cutoff increased the specificity of D-dimer as diagnostic biomarker significantly without any loss in sensitivity [8989. Righini M, Kamphuisen PW and Le Gal G. Age-adjusted D-dimer cutoff levels and pulmonary embolism--reply. JAMA. 2014. ].

Echocardiography

Echocardiography is non-invasive, can immediately be performed at the bedside, provides rapid results, and circumvents radiographic contrast and radiation exposure. Tricuspid insufficiency jet velocity, RV dimensions, disturbed RV ejection pattern or depressed contractility of the RV free wall are accepted as indirect signs of PE. Due to the reportedly low sensitivity of around 60% to70%, echocardiography cannot exclude PE [9090. Grifoni S, Olivotto I, Cecchini P, Pieralli F, Camaiti A, Santoro G, Conti A, Agnelli G and Berni G. Short-term clinical outcome of patients with acute pulmonary embolism, normal blood pressure, and echocardiographic right ventricular dysfunction. Circulation. 2000. , 9191. Miniati M, Monti S, Pratali L, Di Ricco G, Marini C, Formichi B, Prediletto R, Michelassi C, Di Lorenzo M, Tonelli L and Pistolesi M. Value of transthoracic echocardiography in the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism: results of a prospective study in unselected patients. Am J Med. 2001. , 9292. Roy PM, Colombet I, Durieux P, Chatellier G, Sors H and Meyer G. Systematic review and meta-analysis of strategies for the diagnosis of suspected pulmonary embolism. BMJ. 2005. ]. Hence, echocardiographic examination is reserved for haemodynamically unstable, hypotensive patients. Direct visualisation of right heart enlargement and of right heart thrombi, as in 4% to18% of patients with acute PE, justifies the initiation of specific treatment [9393. Casazza F, Bongarzoni A, Centonze F and Morpurgo M. Prevalence and prognostic significance of right-sided cardiac mobile thrombi in acute massive pulmonary embolism. Am J Cardiol. 1997. , 9494. Torbicki A, Galie N, Covezzoli A, Rossi E, De Rosa M and Goldhaber SZ. Right heart thrombi in pulmonary embolism: results from the International Cooperative Pulmonary Embolism Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003. ].

Transoesophageal echocardiography for searching emboli in main pulmonary arteries may be considered for immediate decision-making in patients with severe haemodynamic compromise [9393. Casazza F, Bongarzoni A, Centonze F and Morpurgo M. Prevalence and prognostic significance of right-sided cardiac mobile thrombi in acute massive pulmonary embolism. Am J Cardiol. 1997. , 9494. Torbicki A, Galie N, Covezzoli A, Rossi E, De Rosa M and Goldhaber SZ. Right heart thrombi in pulmonary embolism: results from the International Cooperative Pulmonary Embolism Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003. ], visualising thrombus in the proximal pulmonary arteries [9595. Pruszczyk P, Torbicki A, Kuch-Wocial A, Chlebus M, Miskiewicz ZC and Jedrusik P. Transoesophageal echocardiography for definitive diagnosis of haemodynamically significant pulmonary embolism. Eur Heart J. 1995. , 9696. Rittoo D, Sutherland GR, Samuel L, Flapan AD and Shaw TR. Role of transesophageal echocardiography in diagnosis and management of central pulmonary artery thromboembolism. Am J Cardiol. 1993. ], and in systemic veins and the right heart. However, the proximal part of the left pulmonary artery can be assessed in only 47% of patients [9797. Pruszczyk P, Torbicki A, Kuch-Wocial A, Szulc M, Styczynski G, Bochowicz A and Kostrubiec M. Visualization of the central pulmonary arteries by biplane transesophageal echocardiography. Exp Clin Cardiol. 2001. ].

Computed tomography

CT angiography has replaced pulmonary angiography as the method of choice for imaging the pulmonary vasculature for suspected PE, particularly since the implementation of multidetector CT [5252. Konstantinides SV, Torbicki A, Agnelli G, Danchin N, Fitzmaurice D, Galie N, Gibbs JS, Huisman MV, Humbert M, Kucher N, Lang I, Lankeit M, Lekakis J, Maack C, Mayer E, Meneveau N, Perrier A, Pruszczyk P, Rasmussen LH, Schindler TH, Svitil P, Vonk Noordegraaf A, Zamorano JL, Zompatori M, Task Force for the D and Management of Acute Pulmonary Embolism of the European Society of C. 2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism. Eur Heart J. 2014.

Latest European guidelines on acute pulmonary embolism]. Conventional pulmonary angiography leads to an increased bleeding risk during thrombolysis [9898. Agnelli G, Becattini C and Kirschstein T. Thrombolysis vs heparin in the treatment of pulmonary embolism: a clinical outcome-based meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2002. , 9999. Wan S, Quinlan DJ, Agnelli G and Eikelboom JW. Thrombolysis compared with heparin for the initial treatment of pulmonary embolism: a meta-analysis of the randomized controlled trials. Circulation. 2004. ], and is associated with higher mortality in unstable patients [100100. Stein PD, Athanasoulis C, Alavi A, Greenspan RH, Hales CA, Saltzman HA, Vreim CE, Terrin ML and Weg JG. Complications and validity of pulmonary angiography in acute pulmonary embolism. Circulation. 1992. ] . Multidetector CT is at least as accurate as invasive pulmonary angiography [101101. Piazza G and Goldhaber SZ. Acute pulmonary embolism: part I: epidemiology and diagnosis. Circulation. 2006. , 102102. Quiroz R, Kucher N, Zou KH, Kipfmueller F, Costello P, Goldhaber SZ and Schoepf UJ. Clinical validity of a negative computed tomography scan in patients with suspected pulmonary embolism: a systematic review. JAMA. 2005. ] and allows the adequate visualisation of the pulmonary arteries up to at least the segmental level [103103. Ghaye B, Szapiro D, Mastora I, Delannoy V, Duhamel A, Remy J and Remy-Jardin M. Peripheral pulmonary arteries: how far in the lung does multi-detector row spiral CT allow analysis?. Radiology. 2001. , 104104. Patel S, Kazerooni EA and Cascade PN. Pulmonary embolism: optimization of small pulmonary artery visualization at multi-detector row CT. Radiology. 2003. ] .

A positive CT has a high positive predictive value (92% to 96%) in patients with intermediate or high clinical probability of PE [105105. Stein PD, Fowler SE, Goodman LR, Gottschalk A, Hales CA, Hull RD, Leeper KV, Jr., Popovich J, Jr., Quinn DA, Sos TA, Sostman HD, Tapson VF, Wakefield TW, Weg JG and Woodard PK. Multidetector computed tomography for acute pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2006. ]. Large clinical trials have established Multidetector CT as a reliable method to exclude PE [106106. Elias A, Cazanave A, Elias M, Chabbert V, Juchet H, Paradis H, Carriere P, Nguyen F, Didier A, Galinier M, Colin C, Lauque D, Joffre F and Rousseau H. Diagnostic management of pulmonary embolism using clinical assessment, plasma D-dimer assay, complete lower limb venous ultrasound and helical computed tomography of pulmonary arteries. A multicentre clinical outcome study. Thromb Haemost. 2005. , 107107. van Belle A, Buller HR, Huisman MV, Huisman PM, Kaasjager K, Kamphuisen PW, Kramer MH, Kruip MJ, Kwakkel-van Erp JM, Leebeek FW, Nijkeuter M, Prins MH, Sohne M and Tick LW. Effectiveness of managing suspected pulmonary embolism using an algorithm combining clinical probability, D-dimer testing, and computed tomography. JAMA. 2006. ]. However, whether patients with a negative CT should be further examined by compression ultrasonography (CUS) and/or ventilation-perfusion scintigraphy (V/Q scan) or pulmonary angiography is still controversial [5252. Konstantinides SV, Torbicki A, Agnelli G, Danchin N, Fitzmaurice D, Galie N, Gibbs JS, Huisman MV, Humbert M, Kucher N, Lang I, Lankeit M, Lekakis J, Maack C, Mayer E, Meneveau N, Perrier A, Pruszczyk P, Rasmussen LH, Schindler TH, Svitil P, Vonk Noordegraaf A, Zamorano JL, Zompatori M, Task Force for the D and Management of Acute Pulmonary Embolism of the European Society of C. 2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism. Eur Heart J. 2014.

Latest European guidelines on acute pulmonary embolism].

Ventilation–perfusion scintigraphy

Ventilation–perfusion scintigraphy (V/Q scan) is a validated option for patients with contraindications to CT, such as allergy to iodine contrast dye or renal failure, despite a high proportion of inconclusive results [108108. Value of the ventilation/perfusion scan in acute pulmonary embolism. Results of the prospective investigation of pulmonary embolism diagnosis (PIOPED). The PIOPED Investigators. JAMA. 1990. ].

Lung scan results usually indicate the level of probability of PE according to criteria established in the North American PIOPED trial [108108. Value of the ventilation/perfusion scan in acute pulmonary embolism. Results of the prospective investigation of pulmonary embolism diagnosis (PIOPED). The PIOPED Investigators. JAMA. 1990. ]. In general, V/Q scan results have to be verified by further tests. Only high-probability V/Q scan results in patients with high degree of probability are accepted as diagnosis without further clarification [5252. Konstantinides SV, Torbicki A, Agnelli G, Danchin N, Fitzmaurice D, Galie N, Gibbs JS, Huisman MV, Humbert M, Kucher N, Lang I, Lankeit M, Lekakis J, Maack C, Mayer E, Meneveau N, Perrier A, Pruszczyk P, Rasmussen LH, Schindler TH, Svitil P, Vonk Noordegraaf A, Zamorano JL, Zompatori M, Task Force for the D and Management of Acute Pulmonary Embolism of the European Society of C. 2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism. Eur Heart J. 2014.

Latest European guidelines on acute pulmonary embolism].

Diagnostic algorithm

According to the ESC guidelines [5252. Konstantinides SV, Torbicki A, Agnelli G, Danchin N, Fitzmaurice D, Galie N, Gibbs JS, Huisman MV, Humbert M, Kucher N, Lang I, Lankeit M, Lekakis J, Maack C, Mayer E, Meneveau N, Perrier A, Pruszczyk P, Rasmussen LH, Schindler TH, Svitil P, Vonk Noordegraaf A, Zamorano JL, Zompatori M, Task Force for the D and Management of Acute Pulmonary Embolism of the European Society of C. 2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism. Eur Heart J. 2014.

Latest European guidelines on acute pulmonary embolism], the diagnostic algorithm differs substantially between suspected high-risk and non-high-risk PE. Therefore, prompt and accurate risk stratification to guide appropriate diagnostic steps is of major importance. Both diagnostic algorithms are illustrated in Figure 2 .

Suspected high-risk PE

High-risk PE, characterised by the presence of shock or arterial hypotension, accounts for 5% of all cases of PE and has a short-term mortality of at least 15% [109109. Kasper W, Konstantinides S, Geibel A, Olschewski M, Heinrich F, Grosser KD, Rauber K, Iversen S, Redecker M and Kienast J. Management strategies and determinants of outcome in acute major pulmonary embolism: results of a multicenter registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997. ]. This underlines the potential life-threatening nature of high-risk PE, and the need for emergency treatment. Therefore, a simple and rapid diagnostic algorithm for the diagnosis of PE is of great practical benefit. Crucially, emergency CT or bedside echocardiography is recommended for diagnostic purposes.

Due to its availability in most emergency rooms, bedside transthoracic echocardiography is the most useful initial examination for the diagnosis of right ventricular dysfunction. In the absence of echocardiographic signs of RV overload or dysfunction, massive PE is excluded and the search for other causes is indicated. In the case of positive echocardiographic findings, CT should confirm the diagnosis of PE. In highly unstable patients, or if other tests are not available, echocardiography alone is sufficient to justify rapid treatment. If the patient is stabilised and CT is available, a CT should be performed immediately. After confirming the diagnosis, PE-specific treatment is justified.

Suspected non-high-risk pulmonary embolism

In the majority of patients admitted to the emergency department with suspected PE, the diagnosis can be excluded by careful evaluation. The assessment of clinical probability by the revised Geneva score [8282. Le Gal G, Righini M, Roy PM, Sanchez O, Aujesky D, Bounameaux H and Perrier A. Prediction of pulmonary embolism in the emergency department: the revised Geneva score. Ann Intern Med. 2006. ] and the Wells score [8383. Wells PS, Anderson DR, Rodger M, Ginsberg JS, Kearon C, Gent M, Turpie AG, Bormanis J, Weitz J, Chamberlain M, Bowie D, Barnes D and Hirsh J. Derivation of a simple clinical model to categorize patients probability of pulmonary embolism: increasing the models utility with the SimpliRED D-dimer. Thromb Haemost. 2000. ] is recommended as a first step ( Table 2 and Table 3 ). If the likelihood of PE is low or intermediate, D-dimer measurements as the next diagnostic step that should be performed for ruling out PE. D-dimer determination combined with clinical probability assessment allows PE to be ruled out in around 30% of this patient group [107107. van Belle A, Buller HR, Huisman MV, Huisman PM, Kaasjager K, Kamphuisen PW, Kramer MH, Kruip MJ, Kwakkel-van Erp JM, Leebeek FW, Nijkeuter M, Prins MH, Sohne M and Tick LW. Effectiveness of managing suspected pulmonary embolism using an algorithm combining clinical probability, D-dimer testing, and computed tomography. JAMA. 2006. , 110110. Perrier A, Desmarais S, Miron MJ, de Moerloose P, Lepage R, Slosman D, Didier D, Unger PF, Patenaude JV and Bounameaux H. Non-invasive diagnosis of venous thromboembolism in outpatients. Lancet. 1999. , 111111. Kruip MJ, Slob MJ, Schijen JH, van der Heul C and Buller HR. Use of a clinical decision rule in combination with D-dimer concentration in diagnostic workup of patients with suspected pulmonary embolism: a prospective management study. Arch Intern Med. 2002. , 112112. Perrier A, Roy PM, Aujesky D, Chagnon I, Howarth N, Gourdier AL, Leftheriotis G, Barghouth G, Cornuz J, Hayoz D and Bounameaux H. Diagnosing pulmonary embolism in outpatients with clinical assessment, D-dimer measurement, venous ultrasound, and helical computed tomography: a multicenter management study. Am J Med. 2004. , 113113. Wells PS, Anderson DR, Rodger M, Stiell I, Dreyer JF, Barnes D, Forgie M, Kovacs G, Ward J and Kovacs MJ. Excluding pulmonary embolism at the bedside without diagnostic imaging: management of patients with suspected pulmonary embolism presenting to the emergency department by using a simple clinical model and d-dimer. Ann Intern Med. 2001. ]. In patients with high clinical probability of PE, the measurement of D-Dimer is frequently unhelpful due to its low negative predictive value [114114. Righini M, Aujesky D, Roy PM, Cornuz J, de Moerloose P, Bounameaux H and Perrier A. Clinical usefulness of D-dimer depending on clinical probability and cutoff value in outpatients with suspected pulmonary embolism. Arch Intern Med. 2004. ].

If the likelihood of PE is high, or if the D-dimer is elevated, then CT angiography is indicated. This has become the main thoracic imaging modality for suspected PE [115115. British Thoracic Society guidelines for the management of suspected acute pulmonary embolism. Thorax. 2003. , 116116. Schoepf UJ, Savino G, Lake DR, Ravenel JG and Costello P. The Age of CT Pulmonary Angiography. J Thorac Imaging. 2005. ]. Hence, Multidetector CT is the second-line test in patients with an elevated D-dimer level and the first-line test in patients with a high clinical probability [5252. Konstantinides SV, Torbicki A, Agnelli G, Danchin N, Fitzmaurice D, Galie N, Gibbs JS, Huisman MV, Humbert M, Kucher N, Lang I, Lankeit M, Lekakis J, Maack C, Mayer E, Meneveau N, Perrier A, Pruszczyk P, Rasmussen LH, Schindler TH, Svitil P, Vonk Noordegraaf A, Zamorano JL, Zompatori M, Task Force for the D and Management of Acute Pulmonary Embolism of the European Society of C. 2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism. Eur Heart J. 2014.

Latest European guidelines on acute pulmonary embolism].

THERAPEUTIC STRATEGIES

The treatment of choice depends on the calculated risk of PE-related early mortality. Therefore, accurate risk stratification is crucial for the selection of treatment. The initial risk stratification of suspected and/or confirmed PE based on the presence of shock and hypotension is needed to differentiate between high-risk and non-high-risk patients for selecting appropriate therapeutic strategies.

In non-high-risk PE patients, further stratification to intermediate or low-risk PE patients on the presence of imaging or biochemical markers of RV dysfunction and myocardial injury is recommended. However, anticoagulation with unfractionated heparin should be initiated without delay in high-risk as well as non-high-risk PE patients [5252. Konstantinides SV, Torbicki A, Agnelli G, Danchin N, Fitzmaurice D, Galie N, Gibbs JS, Huisman MV, Humbert M, Kucher N, Lang I, Lankeit M, Lekakis J, Maack C, Mayer E, Meneveau N, Perrier A, Pruszczyk P, Rasmussen LH, Schindler TH, Svitil P, Vonk Noordegraaf A, Zamorano JL, Zompatori M, Task Force for the D and Management of Acute Pulmonary Embolism of the European Society of C. 2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism. Eur Heart J. 2014.

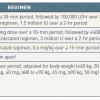

Latest European guidelines on acute pulmonary embolism]. A therapeutic algorithm in accordance with the ESC guidelines is depicted in Figure 3 .

New oral anticoagulants (NOACs)

Rivaroxaban, abixaban and edoxaban are oral factor Xa inhibitors. Dabigatran is an orally administered direct thrombin inhibitor. NOACs do not require laboratory monitoring and have no food interactions and only a few drug interactions [117117. Kubitza D, Becka M, Voith B, Zuehlsdorf M and Wensing G. Safety, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics of single doses of BAY 59-7939, an oral, direct factor Xa inhibitor. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2005. , 118118. Stangier J. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the oral direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran etexilate. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2008. ]. Over the last decades physicians were well trained in the use of conventional anticoagulant treatments with heparin and vitamin K antagonists. Since the new oral anticoagulants (NOACs) received regulatory approval for the acute and continued treatment of PE, physicians are challenged to optimally implement their use in clinical practice. Table 4 helps identify patients that are suitable for treatment with a NOACs. The use of NOACs is not recommended in patients with severe renal impairment. Table 5 gives an overview about dosing of NOACs. A recently published review [119119. Yeh CH, Gross PL and Weitz JI. Evolving use of new oral anticoagulants for treatment of venous thromboembolism. Blood. 2014.

Broad review of contemporary NOACs] summarises in more detail NOACs for the treatment and prevention of thromboembolic diseases.

High-risk pulmonary embolism

High-risk PE patients have a high mortality rate and complication risk [5959. Kucher N, Rossi E, De Rosa M and Goldhaber SZ. Massive pulmonary embolism. Circulation. 2006. , 109109. Kasper W, Konstantinides S, Geibel A, Olschewski M, Heinrich F, Grosser KD, Rauber K, Iversen S, Redecker M and Kienast J. Management strategies and determinants of outcome in acute major pulmonary embolism: results of a multicenter registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997. , 120120. Stein PD and Henry JW. Prevalence of acute pulmonary embolism among patients in a general hospital and at autopsy. Chest. 1995. ]. Acute RV failure with resulting low systemic output is the leading cause of death in patients with high-risk PE. The first few hours after admission to the emergency department are associated with an increased risk of in-hospital death[120120. Stein PD and Henry JW. Prevalence of acute pulmonary embolism among patients in a general hospital and at autopsy. Chest. 1995. ]. Therefore, rapid haemodynamic and respiratory support is of vital importance. The infusion of saline solution is useful to maintain adequate systemic pressure. If the systemic arterial pressure remains below 90 mmHg or if tissue perfusion is not sufficient, the administration of vasopressors or catecholamines is recommended [5959. Kucher N, Rossi E, De Rosa M and Goldhaber SZ. Massive pulmonary embolism. Circulation. 2006. , 109109. Kasper W, Konstantinides S, Geibel A, Olschewski M, Heinrich F, Grosser KD, Rauber K, Iversen S, Redecker M and Kienast J. Management strategies and determinants of outcome in acute major pulmonary embolism: results of a multicenter registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997. ]. Immediate pharmacological or mechanical reopening of the occluded pulmonary arteries is indicated.

Anticoagulation

A parenteral anticoagulation should be administered without delay in haemodynamically unstable patients with suspected PE. Intravenous weight-adjusted unfractionated heparin is the treatment of choice. Subcutaneous LMWH or fondaparinux have not been tested in the setting of hypotension and shock. The anticoagulant effect of unfractionated heparin can be easily monitored and if necessary reversed rapidly by protamine. High-risk PE patients should not receive NOACs in the acute phase as these drugs have not been evaluated in conjunction with primary reperfusion therapies.

Thrombolytic therapy

Systemic thrombolysis improves RV function and haemodynamic status in patients with acute PE [121121. Goldhaber SZ, Haire WD, Feldstein ML, Miller M, Toltzis R, Smith JL, Taveira da Silva AM, Come PC, Lee RT, Parker JA and et al. Alteplase versus heparin in acute pulmonary embolism: randomised trial assessing right-ventricular function and pulmonary perfusion. Lancet. 1993. ]. Therefore, thrombolytic therapy is the first-line treatment that should be immediately administrated in high-risk patients as soon as PE is confirmed. However, the beneficial effects of thrombolysis are limited to the first few days; in survivors, differences disappear one week after administration [122122. Becattini C, Agnelli G, Salvi A, Grifoni S, Pancaldi LG, Enea I, Balsemin F, Campanini M, Ghirarduzzi A, Casazza F and Group TS. Bolus tenecteplase for right ventricle dysfunction in hemodynamically stable patients with pulmonary embolism. Thromb Res. 2010. , 123123. Konstantinides S, Tiede N, Geibel A, Olschewski M, Just H and Kasper W. Comparison of alteplase versus heparin for resolution of major pulmonary embolism. Am J Cardiol. 1998. ].

Because direct local infusion of the thrombolytic agent has not been shown to be advantageous [124124. Verstraete M, Miller GA, Bounameaux H, Charbonnier B, Colle JP, Lecorf G, Marbet GA, Mombaerts P and Olsson CG. Intravenous and intrapulmonary recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator in the treatment of acute massive pulmonary embolism. Circulation. 1988. ], systemic intravenous administration is recommended. Approved thrombolytic agents, regimens, and contraindications are summarised in Table 6 [125125. Konstantinides S. Clinical practice. Acute pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2008. ]. Accelerated thrombolytic regimens are preferable to prolonged infusions of thrombolytic drugs over 12-24 hours [5252. Konstantinides SV, Torbicki A, Agnelli G, Danchin N, Fitzmaurice D, Galie N, Gibbs JS, Huisman MV, Humbert M, Kucher N, Lang I, Lankeit M, Lekakis J, Maack C, Mayer E, Meneveau N, Perrier A, Pruszczyk P, Rasmussen LH, Schindler TH, Svitil P, Vonk Noordegraaf A, Zamorano JL, Zompatori M, Task Force for the D and Management of Acute Pulmonary Embolism of the European Society of C. 2014 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism. Eur Heart J. 2014.

Latest European guidelines on acute pulmonary embolism].

In high-risk PE patients, thrombolysis is associated with a critical reduction of mortality of approximately 22% compared to heparin alone. Despite these impressive outcome data, thrombolysis is withheld in more than two-thirds of patients with high-risk PE according to real world registry data [126126. Lin BW, Schreiber DH, Liu G, Briese B, Hiestand B, Slattery D, Kline JA, Goldhaber SZ and Pollack CV, Jr. Therapy and outcomes in massive pulmonary embolism from the Emergency Medicine Pulmonary Embolism in the Real World Registry. Am J Emerg Med. 2012. , 127127. Stein PD and Matta F. Thrombolytic therapy in unstable patients with acute pulmonary embolism: saves lives but underused. Am J Med. 2012. ]. The reasons for underuse of systemic thrombolysis is unclear and cannot be completely explained by rising catheter-based or surgical revascularisation rates [127127. Stein PD and Matta F. Thrombolytic therapy in unstable patients with acute pulmonary embolism: saves lives but underused. Am J Med. 2012. ]. Challenging the validity of relative contraindications to thrombolysis may help to increase the use of thrombolysis in unstable patients with life-threatening PE.

The main complication of thrombolytic therapy is bleeding. The Pulmonary Embolism Thrombolysis (PEITHO) trial revealed a 2% incidence of haemorrhagic stroke and 6.3% incidence of major non-intracranial bleeding in patients treated with tenecteplase [128128. Meyer G, Vicaut E, Danays T, Agnelli G, Becattini C, Beyer-Westendorf J, Bluhmki E, Bouvaist H, Brenner B, Couturaud F, Dellas C, Empen K, Franca A, Galie N, Geibel A, Goldhaber SZ, Jimenez D, Kozak M, Kupatt C, Kucher N, Lang IM, Lankeit M, Meneveau N, Pacouret G, Palazzini M, Petris A, Pruszczyk P, Rugolotto M, Salvi A, Schellong S, Sebbane M, Sobkowicz B, Stefanovic BS, Thiele H, Torbicki A, Verschuren F, Konstantinides SV and Investigators P. Fibrinolysis for patients with intermediate-risk pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2014.

RCT examining the role of fibrinolysis in patients with pulmonary embolism and markers of intermediate risk], which has led to the recommendation that routine thrombolysis is not recommended in patients who are not in shock.

Interventional treatment

In patients with absolute contraindications and in those whose unstable conditions do not allow sufficient time for systemic thrombolysis to be effective, surgical embolectomy or catheter-directed intervention are alternative reperfusion therapies if appropriate expertise is available [129129. Yalamanchili K, Fleisher AG, Lehrman SG, Axelrod HI, Lafaro RJ, Sarabu MR, Zias EA and Moggio RA. Open pulmonary embolectomy for treatment of major pulmonary embolism. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004. ]. Approximately one third of patients with an acute major PE are not eligible for thrombolysis because of contraindications such as recent surgery, trauma, stroke, advanced cancer or concomitant active bleeding [109109. Kasper W, Konstantinides S, Geibel A, Olschewski M, Heinrich F, Grosser KD, Rauber K, Iversen S, Redecker M and Kienast J. Management strategies and determinants of outcome in acute major pulmonary embolism: results of a multicenter registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997. ]. Furthermore, interventional management should be considered as adjunctive therapy when thrombolysis has failed. Critical clinical conditions which warrant interventional strategies have not been clearly defined. However, several criteria, such as shock with large thrombus burden, severe RV failure with large saddle embolism or moderate RV failure with proximal embolism, justify an interventional approach in a patient with acute PE.

Surgical embolectomy

Historically, surgical embolectomy was restricted to clinically futile circumstances in moribund patients who required cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Over recent years, however, pulmonary embolectomy has become a routine operation with significantly reduced operative risk in centres with established cardiac surgery programmes [129129. Yalamanchili K, Fleisher AG, Lehrman SG, Axelrod HI, Lafaro RJ, Sarabu MR, Zias EA and Moggio RA. Open pulmonary embolectomy for treatment of major pulmonary embolism. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004. , 130130. Leacche M, Unic D, Goldhaber SZ, Rawn JD, Aranki SF, Couper GS, Mihaljevic T, Rizzo RJ, Cohn LH, Aklog L and Byrne JG. Modern surgical treatment of massive pulmonary embolism: results in 47 consecutive patients after rapid diagnosis and aggressive surgical approach. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005. ]. This operation requires rapid induction of anaesthesia, a median sternotomy, incision of the main pulmonary artery, and institution of cardiopulmonary bypass. Emboli can be removed from both pulmonary arteries using forceps under direct vision. Generally, this procedure is performed under normothermia without cardioplegic cardiac arrest [130130. Leacche M, Unic D, Goldhaber SZ, Rawn JD, Aranki SF, Couper GS, Mihaljevic T, Rizzo RJ, Cohn LH, Aklog L and Byrne JG. Modern surgical treatment of massive pulmonary embolism: results in 47 consecutive patients after rapid diagnosis and aggressive surgical approach. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005. ]. The first successful surgical pulmonary embolectomy, called Trendelenburg’s operation, was performed in 1924 [131131. Kirschner M. Ein durch die Trendelenburgsche Operation geheilter Fall von Embolie der Arteria pulmonalis. Arch Klin Chir. 1924. ].

Current guidelines recommend surgical embolectomy in patients with failed thrombolysis and in those with contraindications to thrombolysis. As surgical embolectomy represents a relatively simple operation and outcome is not critically affected by the site of surgical care, delays in treatment by hospital transfer should be avoided as long as an experienced surgeon and cardiopulmonary bypass are available [132132. Kilic A, Shah AS, Conte JV and Yuh DD. Nationwide outcomes of surgical embolectomy for acute pulmonary embolism. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013. ]. Peripheral extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support is a rapid, effective option in critical situations for ensuring circulation and oxygenation until surgical embolectomy can be performed [133133. Malekan R, Saunders PC, Yu CJ, Brown KA, Gass AL, Spielvogel D and Lansman SL. Peripheral extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: comprehensive therapy for high-risk massive pulmonary embolism. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012. ].

Surgical embolectomy represents a valuable treatment option in high-risk PE patients with comparable in-hospital mortality rates and significantly less bleeding complications than thrombolysis [134134. Aymard T, Kadner A, Widmer A, Basciani R, Tevaearai H, Weber A, Schmidli J and Carrel T. Massive pulmonary embolism: surgical embolectomy versus thrombolytic therapy--should surgical indications be revisited?. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2013. ]. In patients with failed thrombolysis, surgical embolectomy significantly improves the haemodynamic status but is associated with increased bleeding rates [135135. Doerge H, Schoendube FA, Voss M, Seipelt R and Messmer BJ. Surgical therapy of fulminant pulmonary embolism: early and late results. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1999. , 136136. Meneveau N, Seronde MF, Blonde MC, Legalery P, Didier-Petit K, Briand F, Caulfield F, Schiele F, Bernard Y and Bassand JP. Management of unsuccessful thrombolysis in acute massive pulmonary embolism. Chest. 2006. ].