Detection of coronary artery disease

Non-invasive imaging and coronary disease

- Imaging is useful to confirm the diagnosis of coronary artery disease in patients with intermediate pre-test likelihood of disease

- While non-invasive angiography can reliably rule out the presence of obstructive coronary artery disease, demonstration of myocardial ischaemia with the use of functional testing is recommended before elective invasive procedures

- Combined and hybrid imaging with anatomical and functional imaging modalities is attractive for comprehensive evaluation of anatomy and functional significance of coronary stenosis

ANATOMICAL IMAGING

Coronary computed tomography angiography

- Coronary computed tomography angiography has become a routine clinical tool for the non-invasive evaluation of the lumen and walls of the coronary arteries with acceptable radiation dose

- Computed tomography angiography can reliably rule out the presence of obstructive coronary artery disease in the presence of low to intermediate pre-test likelihood

- Artefacts caused by coronary calcification or irregular heart rate constitute problems for computed tomography angiography

Coronary computed tomography angiography

The traditional pathways to evaluate patients with coronary artery disease have recently been challenged by coronary computed tomography angiography (CTA), which has rapidly developed to become a widely used non-invasive imaging modality for anatomical detection of CAD [33. Taylor AJ, Cerqueira M, Hodgson JM, Mark D, Min J, O’Gara P, Rubin GD; American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force. ; Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography. ; American College of Radiology. ; American Heart Association. ; American Society of Echocardiography. ; American Society of Nuclear Cardiology. ; North American Society for Cardiovascular Imaging. ; Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. ; Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. , Kramer CM, Berman D, Brown A, Chaudhry FA, Cury RC, Desai MY, Einstein AJ, Gomes AS, Harrington R, Hoffmann U, Khare R, Lesser J, McGann C, Rosenberg A, Schwartz R, Shelton M, Smetana GW, Smith SC Jr. ACCF/SCCT/ACR/AHA/ASE/ASNC/NASCI/SCAI/SCMR 2010 appropriate use criteria for cardiac computed tomography. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, the American College of Radiology, the American Heart Association, the American Society of Echocardiography, the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, the North American Society for Cardiovascular Imaging, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010 56:1864-94.

Comprehensive review of implementa¬tion of non-invasive coronary angiography, 44. Schroeder S, Achenbach S, Bengel F, Burgstahler C, Cademartiri F, de Feyter P, George R, Kaufmann P, Kopp AF, Knuuti J, Ropers D, Schuijf J, Tops LF, Bax JJ; Working Group Nuclear Cardiology and Cardiac CT; European Society of Cardiology; European Council of Nuclear Cardiology. Cardiac computed tomography: indications, applications, limitations, and training requirements: report of a Writing Group deployed by the Working Group Nuclear Cardiology and Cardiac CT of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Council of Nuclear Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:531-56.

Comprehensive review of the current applications and limitations for clinical use of cardiac computed tomog¬raphy angiography]. Coronary CTA is performed using contrast-enhanced imaging and can offer detection of luminal stenosis and visualization of coronary vessel wall ( Figure 1). Iodinated contrast agent is injected through a peripheral cannula, and imaging is timed to peak contrast enhancement in the coronary arteries. Prospective ECG triggering or retrospective ECG gating is used to acquire images during a single breath hold. Use of 64-multidetector scanners produces images of the heart composed of a number of sections acquired during consecutive beats, whereas scanners with more detectors (246 to 320) can acquire images of the entire cardiac volume within a single beat. Guidelines have been published on how to perform and acquire [55. Abbara S, Blanke P, Maroules CD, Cheezum M, Choi AD, Han BK, Marwan M, Naoum C, Norgaard BL, Rubinshtein R, Schoenhagen P, Villines T, Leipsic J. SCCT guidelines for the performance and acquisition of coronary computed tomographic angiography: A report of the society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography Guidelines Committee: Endorsed by the North American Society for Cardiovascular Imaging (NASCI). J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2016;10:435-449. ] as well as interpret and report [66. Leipsic J, Abbara S, Achenbach S, Cury R, Earls JP, Mancini GJ, Nieman K, Pontone G, Raff GL. SCCT guidelines for the interpretation and reporting of coronary CT angiography: a report of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography Guidelines Committee. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2014;8:342-58. ] coronary CTA.

Coronary CTA demonstrates excellent diagnostic accuracy for the detection of obstructive luminal stenosis compared with invasive coronary angiography. A meta-analysis including 27 studies and 3674 patients studied with at least 64-section scanner described a sensitivity of 95% and specificity of 90% for coronary CTA on at the vessel-level to detect significant stenosis [77. Paech DC, Weston AR. A systematic review of the clinical effectiveness of 64-slice or higher computed tomography angiography as an alternative to invasive coronary angiography in the investigation of suspected coronary artery disease. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2011;11:32. ]. Negative predictive value was 99% and positive predictive value 75%. Similar results have been obtained in two multi-center studies examining coronary CTA in patients without history of CAD [88. Budoff MJ, Dowe D, Jollis JG, Gitter M, Sutherland J, Halamert E, Scherer M, Bellinger R, Martin A, Benton R, Delago A, Min JK. Diagnostic performance of 64-multidetector row coronary computed tomographic angiography for evaluation of coronary artery stenosis in individuals without known coronary artery disease: results from the prospective multicenter ACCURACY (Assessment by Coronary Computed Tomographic Angiography of Individuals Undergoing Invasive Coronary Angiography) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;52:1724-32. , 99. Meijboom WB, Meijs MF, Schuijf JD, Cramer MJ, Mollet NR, van Mieghem CA, Nieman K, van Werkhoven JM, Pundziute G, Weustink AC, de Vos AM, Pugliese F, Rensing B, Jukema JW, Bax JJ, Prokop M, Doevendans PA, Hunink MG, Krestin GP, de Feyter PJ. Diagnostic accuracy of 64-slice computed tomography coronary angiography: a prospective, multicenter, multivendor study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;52:2135-44. ]. An excellent negative predictive value (>95%) has been a consistent finding across all studies indicating that coronary CTA can reliably rule out the presence of hemodynamically significant CAD ( Figure 2.).

Good image quality of coronary CTA depends on appropriate patient selection and preparation. Although rate of non-evaluable segments is low, they are still observed, and typically relate to the presence of motion artifacts or blooming effect caused by dense calcification [1010. Menke J, Unterberg-Buchwald C, Staab W, Sohns JM, Seif Amir Hosseini A, Schwarz A. Head-to-head comparison of prospectively triggered vs retrospectively gated coronary computed tomography angiography: Meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy, image quality, and radiation dose. Am Heart J 2013;165:154-63. ]. In order to avoid motion artifacts, it is important to aim at heart rate ≤60 beats/min using beta-blocker administration before scan. Appropriate patient selection is also important due to moderate radiation exposure associated with Coronary CTA. In a meta-analysis of studies using prospective ECG triggering, pooled effective radiation dose was 3.5 mSv, which is significantly lower than the effective dose of retrospectively gated scan (12.3 mSv) [1010. Menke J, Unterberg-Buchwald C, Staab W, Sohns JM, Seif Amir Hosseini A, Schwarz A. Head-to-head comparison of prospectively triggered vs retrospectively gated coronary computed tomography angiography: Meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy, image quality, and radiation dose. Am Heart J 2013;165:154-63. ]. Advances in scanner technology, including faster scanners, wider detector arrays, increased spatial resolution, new reconstruction algorithms, motion correction algorithms, and dual-source imaging, have potential to further reduce image artefacts and radiation exposure.

Coronary CTA provides prognostic information on likelihood of cardiovascular events. A stepwise increase in all-cause mortality associated with 1-, 2-, and 3-vessel disease has been observed in CONFIRM registry of 23,854 patients without known coronary artery disease [1111. Min JK, Shaw LJ, Devereux RB, Okin PM, Weinsaft JW, Russo DJ, Lippolis NJ, Berman DS, Callister TQ. Prognostic value of multidetector coronary computed tomographic angiography for prediction of all-cause mortality. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:1161-70. , 1212. Min JK, Dunning A, Lin FY, Achenbach S, Al-Mallah M, Budoff MJ, Cademartiri F, Callister TQ, Chang HJ, Cheng V, Chinnaiyan K, Chow BJ, Delago A, Hadamitzky M, Hausleiter J, Kaufmann P, Maffei E, Raff G, Shaw LJ, Villines T, Berman DS; CONFIRM Investigators. Age- and sex-related differences in all-cause mortality risk based on coronary computed tomography angiography findings results from the International Multicenter CONFIRM (Coronary CT Angiography Evaluation for Clinical Outcomes: An International Multicenter Registry) of 23,854 patients without known coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:849-60. ]. Furthermore, non-obstructive coronary artery disease is associated with adverse prognosis compared with patients with normal coronary CTA. Studies have also confirmed an excellent prognosis for patients with a normal coronary CTA, with the risk of cardiovascular effects of <0.5% that extends up to 5 years of follow-up [1212. Min JK, Dunning A, Lin FY, Achenbach S, Al-Mallah M, Budoff MJ, Cademartiri F, Callister TQ, Chang HJ, Cheng V, Chinnaiyan K, Chow BJ, Delago A, Hadamitzky M, Hausleiter J, Kaufmann P, Maffei E, Raff G, Shaw LJ, Villines T, Berman DS; CONFIRM Investigators. Age- and sex-related differences in all-cause mortality risk based on coronary computed tomography angiography findings results from the International Multicenter CONFIRM (Coronary CT Angiography Evaluation for Clinical Outcomes: An International Multicenter Registry) of 23,854 patients without known coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:849-60. , 1313. Hadamitzky M1, Täubert S, Deseive S, Byrne RA, Martinoff S, Schömig A, Hausleiter J. Prognostic value of coronary computed tomography angiography during 5 years of follow-up in patients with suspected coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:3277-85. ]. Although obstructive and non-obstructive atherosclerosis on coronary CTA is predictive of cardiovascular events in asymptomatic individuals, a randomized clinical trial did not find benefit from screening of CAD by coronary CTA in asymptomatic diabetic individuals [1414. Muhlestein JB, Lappé DL, Lima JA, Rosen BD, May HT, Knight S, Bluemke DA, Towner SR, Le V, Bair TL, Vavere AL, Anderson JL. Effect of screening for coronary artery disease using CT angiography on mortality and cardiac events in high-risk patients with diabetes: the FACTOR-64 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312:2234-43. ].

Recently, 2 large multicenter randomized controlled trials have addressed the usefulness of coronary CTA in clinical assessment of patients with stable chest pain. The PROMISE trial randomized 10003 symptomatic stable patients (mean age 62 years, pre-test probability of CAD 53%) to initial evaluation with coronary CTA or to functional testing. There were no differences in outcomes between the 2 strategies at 25 months follow-up, indicating that coronary CTA can be safely used in the management of patients with suspected CAD [1515. Douglas PS, Hoffmann U, Patel MR, Mark DB, Al-Khalidi HR, Cavanaugh B, Cole J, Dolor RJ, Fordyce CB, Huang M, Khan MA, Kosinski AS, Krucoff MW, Malhotra V, Picard MH, Udelson JE, Velazquez EJ, Yow E, Cooper LS, Lee KL; PROMISE Investigators. Outcomes of anatomical versus functional testing for coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1291-300. ]. The SCOT-HEART study randomized 4146 patients with suspected angina due to CAD (mean age 58 years and pre-test probability of CAD 47%) to standard care (including high rates of stress testing) or standard care added the coronary CTA [1616. SCOT-HEART investigators. CT coronary angiography in patients with suspected angina due to coronary heart disease (SCOT-HEART): an open-label, parallel-group, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2015;385:2383-91. ]. The addition of coronary CTA improved diagnostic certainty and reduced rates of normal invasive coronary angiography. Current clinical guidelines recommend coronary CTA for ruling out CAD in those with low or intermediate pre-test likelihood of disease [11. Montalescot G, Sechtem U, Achenbach S, Andreotti F, Arden C, Budaj A, Bugiardini R, Crea F, Cuisset T, Di Mario C, Ferreira JR, Gersh BJ, Gitt AK, Hulot JS, Marx N, Opie LH, Pfisterer M, Prescott E, Ruschitzka F, Sabaté M, Senior R, Taggart DP, van der Wall EE, Vrints CJ; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines, Zamorano JL, Achenbach S, Baumgartner H, Bax JJ, Bueno H, Dean V, Deaton C, Erol C, Fagard R, Ferrari R, Hasdai D, Hoes AW, Kirchhof P, Knuuti J, Kolh P, Lancellotti P, Linhart A, Nihoyannopoulos P, Piepoli MF, Ponikowski P, Sirnes PA, Tamargo JL, Tendera M, Torbicki A, Wijns W, Windecker S; Document Reviewers, Knuuti J, Valgimigli M, Bueno H, Claeys MJ, Donner-Banzhoff N, Erol C, Frank H, Funck-Brentano C, Gaemperli O, Gonzalez-Juanatey JR, Hamilos M, Hasdai D, Husted S, James SK, Kervinen K, Kolh P, Kristensen SD, Lancellotti P, Maggioni AP, Piepoli MF, Pries AR, Romeo F, Rydén L, Simoons ML, Sirnes PA, Steg PG, Timmis A, Wijns W, Windecker S, Yildirir A, Zamorano JL. 2013 ESC guidelines on the management of stable coronary artery disease: the Task Force on the management of stable coronary artery disease of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2949-3003.

This paper includes diagnostic algorithms and sets out guidelines for the application of non-invasive testing for evaluating the likelihood of obstructive coronary artery disease in patients with stable angina, 22. Windecker S, Kolh P, Alfonso F, Collet JP, Cremer J, Falk V, Filippatos G, Hamm C, Head SJ, Jüni P, Kappetein AP, Kastrati A, Knuuti J, Landmesser U, Laufer G, Neumann FJ, Richter DJ, Schauerte P, Sousa Uva M, Stefanini GG, Taggart DP, Torracca L, Valgimigli M, Wijns W, Witkowski A. 2014 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization: The Task Force on Myocardial Revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS)Developed with the special contribution of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI). Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2541-619.

Guidelines for applying non-invasive imaging tech¬niques in diagnostic algorithms for evaluating the like¬lihood of obstructive coronary artery disease in patients with stable angina].

Several studies including three randomized controlled trials have assessed the utility of coronary CTA in patients who attend the emergency department with acute chest pain and present with low risk of acute coronary syndrome [1717. Samad Z, Hakeem A, Mahmood SS, Pieper K, Patel MR, Simel DL, Douglas PS. A meta-analysis and systematic review of computed tomography angiography as a diagnostic triage tool for patients with chest pain presenting to the emergency department. J Nucl Cardiol 2012;19:364-76. , 1818. Litt HI, Gatsonis C, Snyder B, Singh H, Miller CD, Entrikin DW, Leaming JM, Gavin LJ, Pacella CB, Hollander JE. CT angiography for safe discharge of patients with possible acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 2012;366:1393-403. , 1919. Hoffmann U, Truong QA, Schoenfeld DA, Chou ET, Woodard PK, Nagurney JT, Pope JH, Hauser TH, White CS, Weiner SG, Kalanjian S, Mullins ME, Mikati I, Peacock WF, Zakroysky P, Hayden D, Goehler A, Lee H, Gazelle GS, Wiviott SD, Fleg JL, Udelson JE; ROMICAT-II Investigators. Coronary CT angiography versus standard evaluation in acute chest pain. N Engl J Med 2012;367:299-308. , 2020. Goldstein JA, Chinnaiyan KM, Abidov A, Achenbach S, Berman DS, Hayes SW, Hoffmann U, Lesser JR, Mikati IA, O’Neil BJ, Shaw LJ, Shen MY, Valeti US, Raff GL; CT-STAT Investigators. The CT-STAT (Coronary Computed Tomographic Angiography for Systematic Triage of Acute Chest Pain Patients to Treatment) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58:1414-22. ]. These studies have demonstrated that early coronary CTA can safely exclude acute coronary syndrome, accelerates diagnosis and hence, expedites either discharge or initiation of therapy. However, coronary CTA did not reduce rates of invasive coronary angiography in the acute setting. Furthermore, it is not feasible in all patients with for example due to rapid heart rate. Based on these studies, the use of coronary CTA has emerged as an option to assess selected patients with acute chest pain.

The value of coronary CTA is different in patients with and without known CAD. Limitations of image quality due to coronary calcification, coronary stents, or vascular clips can reduce diagnostic accuracy in patients with known CAD and previous revascularization. The assessment of venous grafts in patients who have undergone coronary artery bypass graft surgery is feasible and coronary CTA provides high sensitivity (89% to 98%) and specificity (89% to 97%) for the identification of 50% stenosis on invasive coronary angiography [44. Schroeder S, Achenbach S, Bengel F, Burgstahler C, Cademartiri F, de Feyter P, George R, Kaufmann P, Kopp AF, Knuuti J, Ropers D, Schuijf J, Tops LF, Bax JJ; Working Group Nuclear Cardiology and Cardiac CT; European Society of Cardiology; European Council of Nuclear Cardiology. Cardiac computed tomography: indications, applications, limitations, and training requirements: report of a Writing Group deployed by the Working Group Nuclear Cardiology and Cardiac CT of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Council of Nuclear Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:531-56.

Comprehensive review of the current applications and limitations for clinical use of cardiac computed tomog¬raphy angiography]. However, evaluation of native vessels may be limited by extensive atherosclerosis and calcification. The accurate evaluation of coronary stents with coronary CTA depends on the material and diameter of the stent, with image artifacts related to the stents’ metallic structure preventing assessment of 9% to 11% of stents [2121. Carrabba N, Schuijf JD, de Graaf FR, Parodi G, Maffei E, Valenti R, Palumbo A, Weustink AC, Mollet NR, Accetta G, Cademartiri F, Antoniucci D, Bax JJ. Diagnostic accuracy of 64-slice computed tomography coronary angiography for the detection of in-stent restenosis: a meta-analysis. J Nucl Cardiol. 2010;17:470–8. ]. Assessment of stents>3 mm in diameter is often feasible, with relatively high sensitivities and specificities for detecting in-stent restenosis [2121. Carrabba N, Schuijf JD, de Graaf FR, Parodi G, Maffei E, Valenti R, Palumbo A, Weustink AC, Mollet NR, Accetta G, Cademartiri F, Antoniucci D, Bax JJ. Diagnostic accuracy of 64-slice computed tomography coronary angiography for the detection of in-stent restenosis: a meta-analysis. J Nucl Cardiol. 2010;17:470–8. ].

Coronary artery calcium (CAC) scoring uses non-contrast ECG –gated CT to provide measures of coronary atherosclerotic burden. Macroscopic calcification within coronary arteries can be accurately quantified using the Agatston score [2222. Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, Albus C, Brotons C, Catapano AL, Cooney MT, Corrà U, Cosyns B, Deaton C, Graham I, Hall MS, Hobbs FD, Løchen ML, Löllgen H, Marques-Vidal P, Perk J, Prescott E, Redon J, Richter DJ, Sattar N, Smulders Y, Tiberi M, van der Worp HB, van Dis I, Verschuren WM; Authors/Task Force Members. 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: The Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts)Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2315-81. ]. Coronary calcification is a highly specific for atherosclerosis, but it is not possible to detect or rule out the presence of obstructive coronary artery disease based on coronary artery calcium imaging alone. Several population-based studies demonstrate that CAC scoring provides powerful prognostic information on adverse cardiovascular events [2222. Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, Albus C, Brotons C, Catapano AL, Cooney MT, Corrà U, Cosyns B, Deaton C, Graham I, Hall MS, Hobbs FD, Løchen ML, Löllgen H, Marques-Vidal P, Perk J, Prescott E, Redon J, Richter DJ, Sattar N, Smulders Y, Tiberi M, van der Worp HB, van Dis I, Verschuren WM; Authors/Task Force Members. 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: The Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts)Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2315-81. , 2323. Detrano R, Guerci AD, Carr JJ, Bild DE, Burke G, Folsom AR, Liu K, Shea S, Szklo M, Bluemke DA, O’Leary DH, Tracy R, Watson K, Wong ND, Kronmal RA. Coronary calcium as a predictor of coronary events in four racial or ethnic groups. N Engl J Med 2008;358:1336–45. , 2424. Erbel R, Mohlenkamp S, Moebus S, Schmermund A, Lehmann N, Stang A, Dragano N, Grönemeyer D, Seibel R, Kälsch H, Bröcker-Preuss M, Mann K, Siegrist J, Jöckel KH; Heinz Nixdorf Recall Study Investigative Group. Coronary risk stratification, discrimination, and reclassification improvement based on quantification of subclinical coronary atherosclerosis: the Heinz Nixdorf Recall study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;56:1397–406. ]. Addition of calcium scoring to Framingham risk scores improves prediction of coronary events. In asymptomatic and otherwise low- or intermediate-risk patients, CAC score of zero is associated with excellent prognosis, i.e. <1% annual mortality rate for up to 15 years. Even small amounts of CAC are associated with increase in risk, and the risk gradually increases with increasing amount of calcium [2323. Detrano R, Guerci AD, Carr JJ, Bild DE, Burke G, Folsom AR, Liu K, Shea S, Szklo M, Bluemke DA, O’Leary DH, Tracy R, Watson K, Wong ND, Kronmal RA. Coronary calcium as a predictor of coronary events in four racial or ethnic groups. N Engl J Med 2008;358:1336–45. , 2424. Erbel R, Mohlenkamp S, Moebus S, Schmermund A, Lehmann N, Stang A, Dragano N, Grönemeyer D, Seibel R, Kälsch H, Bröcker-Preuss M, Mann K, Siegrist J, Jöckel KH; Heinz Nixdorf Recall Study Investigative Group. Coronary risk stratification, discrimination, and reclassification improvement based on quantification of subclinical coronary atherosclerosis: the Heinz Nixdorf Recall study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;56:1397–406. ].

European guidelines (indicate that CAC scoring may be considered as a risk modifier in cardiovascular risk assessment (Class IIb, level of evidence B), particularly in patients at intermediate clinical risk [2222. Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, Albus C, Brotons C, Catapano AL, Cooney MT, Corrà U, Cosyns B, Deaton C, Graham I, Hall MS, Hobbs FD, Løchen ML, Löllgen H, Marques-Vidal P, Perk J, Prescott E, Redon J, Richter DJ, Sattar N, Smulders Y, Tiberi M, van der Worp HB, van Dis I, Verschuren WM; Authors/Task Force Members. 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: The Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts)Developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2315-81. ]. However, the reduction of cardiovascular disease risk in primary prevention of patients treated with lipid- or blood pressure lowering medications because of reclassification with CAC scoring remains to be demonstrated. Radiation dose associated with the scan is small, i.e. approximately 1 to 2 mSv, but it remains a concern in the context of wide-spread population-based screening programs.

Coronary CTA performed using contrast-enhanced imaging and can offer detailed visualization of both calcified and con-calcified coronary atherosclerotic plaque [2525. Voros S, Rinehart S, Qian Z, Joshi P, Vazquez G, Fischer C, Belur P, Hulten E, Villines TC. Coronary atherosclerosis imaging by coronary CT angiography: current status, correlation with intravascular interrogation and meta-analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2011;4: 537-48. ]. Clinically, individual plaques are categorized as noncalcified (no calcium), calcified (entire plaque appears as calcified) or partially calcified (mix of calcified and low attenuation plaque components). Furthermore, it is possible to identify other plaque characteristics that are associated with adverse cardiovascular events, including positive remodeling, necrotic core, napkin ring sign, and spotty calcification. Positive remodeling is defined by eccentric plaque formation with relative preservation of the lumen area. Regions of low-attenuation plaque identify a large necrotic core. Appearance of a napkin ring sign is associated with low attenuation surrounded by a rim of high attenuation. Spotty calcification likely reflects early atherosclerotic calcification. Visual assessment of plaque features is time-consuming and challenging, but improvements in CT image quality and post-processing, such as automated quantification methods, may improve further delineation of plaque characteristics. These features are more common in patients with acute coronary syndrome than those with stable angina and they are associated with rate of cardiovascular events during follow-up. However, value of these features in risk assessment remains to be determined in prospective studies.

Current clinical indications

Current guidelines recommend coronary CTA as an alternative to the exercise ECG to exclude CAD in symptomatic stable patients with intermediate pre-test probability of CAD especially when the ECG is uninterpretable or when patients are unable to exercise. The high negative predictive value makes CTA especially useful in patients with lower range of intermediate pre-test probability. Patients with an uninterpretable or equivocal stress test are a further group where CTA is useful. In selected patients with acute chest pain, intermediate pre-test probability of CAD and no ECG or biomarker changes CTA may also be used to detect CAD. CTA may also be considered in patients in patients with heart failure and low to intermediate pre-test probability of CAD to rule out CAD. The patients for whom CTA is not recommended are those with pronounced coronary calcification or irregular heart rate that are associated with high probability of non-diagnostic image quality, and patients with high pre-test likelihood of CAD. In addition, CTA should not currently be used to assess the severity and significance of known CAD in patients with prior revascularisation or to screen asymptomatic subjects for CAD [11. Montalescot G, Sechtem U, Achenbach S, Andreotti F, Arden C, Budaj A, Bugiardini R, Crea F, Cuisset T, Di Mario C, Ferreira JR, Gersh BJ, Gitt AK, Hulot JS, Marx N, Opie LH, Pfisterer M, Prescott E, Ruschitzka F, Sabaté M, Senior R, Taggart DP, van der Wall EE, Vrints CJ; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines, Zamorano JL, Achenbach S, Baumgartner H, Bax JJ, Bueno H, Dean V, Deaton C, Erol C, Fagard R, Ferrari R, Hasdai D, Hoes AW, Kirchhof P, Knuuti J, Kolh P, Lancellotti P, Linhart A, Nihoyannopoulos P, Piepoli MF, Ponikowski P, Sirnes PA, Tamargo JL, Tendera M, Torbicki A, Wijns W, Windecker S; Document Reviewers, Knuuti J, Valgimigli M, Bueno H, Claeys MJ, Donner-Banzhoff N, Erol C, Frank H, Funck-Brentano C, Gaemperli O, Gonzalez-Juanatey JR, Hamilos M, Hasdai D, Husted S, James SK, Kervinen K, Kolh P, Kristensen SD, Lancellotti P, Maggioni AP, Piepoli MF, Pries AR, Romeo F, Rydén L, Simoons ML, Sirnes PA, Steg PG, Timmis A, Wijns W, Windecker S, Yildirir A, Zamorano JL. 2013 ESC guidelines on the management of stable coronary artery disease: the Task Force on the management of stable coronary artery disease of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2949-3003.

This paper includes diagnostic algorithms and sets out guidelines for the application of non-invasive testing for evaluating the likelihood of obstructive coronary artery disease in patients with stable angina, 22. Windecker S, Kolh P, Alfonso F, Collet JP, Cremer J, Falk V, Filippatos G, Hamm C, Head SJ, Jüni P, Kappetein AP, Kastrati A, Knuuti J, Landmesser U, Laufer G, Neumann FJ, Richter DJ, Schauerte P, Sousa Uva M, Stefanini GG, Taggart DP, Torracca L, Valgimigli M, Wijns W, Witkowski A. 2014 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization: The Task Force on Myocardial Revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS)Developed with the special contribution of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI). Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2541-619.

Guidelines for applying non-invasive imaging tech¬niques in diagnostic algorithms for evaluating the like¬lihood of obstructive coronary artery disease in patients with stable angina, 33. Taylor AJ, Cerqueira M, Hodgson JM, Mark D, Min J, O’Gara P, Rubin GD; American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force. ; Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography. ; American College of Radiology. ; American Heart Association. ; American Society of Echocardiography. ; American Society of Nuclear Cardiology. ; North American Society for Cardiovascular Imaging. ; Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. ; Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. , Kramer CM, Berman D, Brown A, Chaudhry FA, Cury RC, Desai MY, Einstein AJ, Gomes AS, Harrington R, Hoffmann U, Khare R, Lesser J, McGann C, Rosenberg A, Schwartz R, Shelton M, Smetana GW, Smith SC Jr. ACCF/SCCT/ACR/AHA/ASE/ASNC/NASCI/SCAI/SCMR 2010 appropriate use criteria for cardiac computed tomography. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, the American College of Radiology, the American Heart Association, the American Society of Echocardiography, the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, the North American Society for Cardiovascular Imaging, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010 56:1864-94.

Comprehensive review of implementa¬tion of non-invasive coronary angiography]. It should also be noted that detection of coronary calcium is not recommended for the detection of coronary stenosis.

Coronary magnetic resonance angiography

Coronary magnetic resonance (MR) angiography is technically challenging and is not being used to the same extent as coronary CTA [2626. Dweck MR, Puntman V, Vesey AT, Fayad ZA, Nagel E. MR Imaging of Coronary Arteries and Plaques. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9:306-16. ]. However, there is continuous interest in coronary MR angiography, because it has some advantages over coronary CTA. These include lack of patient exposure to ionising radiation and images that are free from calcification related artefacts. Furthermore, superior soft tissue characterization offered by MR is potentially well suited for characterization of atherosclerotic burden and plaque characteristics. However, translation of plaque analysis from carotid arteries to coronary arteries has proved challenging.

Acquisition of coronary MR images takes much longer than CTA and it is not possible during single breath-hold. Current sequences for coronary imaging based on ECG gating coupled with respiratory navigator take several minutes to acquire. The major challenge of coronary MR is to obtain sufficient amount of data for high resolution imaging while correcting for motion caused by cardiac contraction and respiration. The first multicentre study investigating accuracy of coronary MR angiography for obstructive coronary artery disease reported overall sensitivity of 93% and specificity of 42% when compared with invasive coronary angiography. A subsequent meta-analysis reported sensitivity of 88% and specificity of 72%. With recent technical advances (such as whole-heart coronary MR angiography using a free-breathing 3-dimensional whole heart steady-state free precession sequences) further improvements in sensitivity (91%) and specificity (86%) have been reported. Accuracy has been variable between coronary segments with the proximal and middle parts being most feasible to evaluate. Although the patency of bypass grafts can be determined with coronary MR angiography, there are artefacts from clips and distal anastomose are difficult to evaluate.

Current clinical indications

Coronary MR angiography has lower success rate and is less accurate than coronary CTA in the detection of obstructive CAD. Thus, current Appropriateness Use Criteria do not recommend its use for the assessment of native coronary arteries. However, it is suitable for the assessment of anomalous coronary arteries with aberrant origins and for detecting coronary artery aneurysms, especially in children and young adults [22. Windecker S, Kolh P, Alfonso F, Collet JP, Cremer J, Falk V, Filippatos G, Hamm C, Head SJ, Jüni P, Kappetein AP, Kastrati A, Knuuti J, Landmesser U, Laufer G, Neumann FJ, Richter DJ, Schauerte P, Sousa Uva M, Stefanini GG, Taggart DP, Torracca L, Valgimigli M, Wijns W, Witkowski A. 2014 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization: The Task Force on Myocardial Revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS)Developed with the special contribution of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI). Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2541-619.

Guidelines for applying non-invasive imaging tech¬niques in diagnostic algorithms for evaluating the like¬lihood of obstructive coronary artery disease in patients with stable angina, 33. Taylor AJ, Cerqueira M, Hodgson JM, Mark D, Min J, O’Gara P, Rubin GD; American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force. ; Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography. ; American College of Radiology. ; American Heart Association. ; American Society of Echocardiography. ; American Society of Nuclear Cardiology. ; North American Society for Cardiovascular Imaging. ; Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. ; Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. , Kramer CM, Berman D, Brown A, Chaudhry FA, Cury RC, Desai MY, Einstein AJ, Gomes AS, Harrington R, Hoffmann U, Khare R, Lesser J, McGann C, Rosenberg A, Schwartz R, Shelton M, Smetana GW, Smith SC Jr. ACCF/SCCT/ACR/AHA/ASE/ASNC/NASCI/SCAI/SCMR 2010 appropriate use criteria for cardiac computed tomography. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, the American College of Radiology, the American Heart Association, the American Society of Echocardiography, the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, the North American Society for Cardiovascular Imaging, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010 56:1864-94.

Comprehensive review of implementa¬tion of non-invasive coronary angiography, 2626. Dweck MR, Puntman V, Vesey AT, Fayad ZA, Nagel E. MR Imaging of Coronary Arteries and Plaques. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9:306-16. ].

FUNCTIONAL IMAGING

Myocardial ischaemia

- Documentation of ischaemia using functional testing is strongly recommended before elective invasive procedures for coronary artery disease

- Stress echocardiography and SPECT perfusion imaging are the most well-established techniques for the detection of myocardial ischaemia, but a growing amount of data about cardiovascular MR and PET is becoming available

- Detection of a large area of myocardial ischaemia by functional imaging is associated with impaired prognosis of patients

Stress echo

Stress echocardiography is a well-established imaging method to detect CAD based on monitoring wall motion abnormalities induced in response to exercise or pharmacological stress [2727. Sicari R, Nihoyannopoulos P, Evangelista A, Kasprzak J, Lancellotti P, Poldermans D, Voigt JU, Zamorano JL; European Association of Echocardiography. Stress echocardiography expert consensus statement: European Association of Echocardiography (EAE) (a registered branch of the ESC). Eur J Echocardiogr. 2008;9:415-37.

Practice guidelines and review of evidence for perform¬ing stress echocardiography in evaluation of coronary artery disease]. The wall motion and wall thickening are analysed in the images using a 4-point scale: 1) normokinesia or hyperkinesia, i.e., normal or hyperkinetic inward systolic motion of the endocardium and wall thickening; 2) hypokinesia, i.e., reduced inward systolic motion of the endocardium and wall thickening; 3) akinesia, i.e., absence of inward systolic motion of the endocardium and wall thickening; 4) dyskinesia, i.e., abnormal outward systolic motion of the endocardium and systolic wall thinning. The test is considered positive when wall motion or wall thickening deteriorates by one grade or more in any myocardial segment as demonstrated in Figure 3 . Timing of the events is also important, because ischaemia can result in delayed motion and thickening (post-systolic thickening). It is recommended that wall motion abnormalities be assigned to a region of one of the three coronary arteries using a model with 17 myocardial segments. However, it is important to realise that there is anatomic variability in coronary artery supply to the myocardium.

Stress echocardiography allows the detection of inducible ischaemia, the differentiation of ischaemic, but viable, myocardium from scar tissue, and the study of the extent or localisation of ischaemia. The wall motion responses to stress follow four basic patterns. The normal response to exercise test is that normokinetic segments remain normokinetic or become hyperkinetic during stress. In the presence of reversible ischaemia, normokinetic segments become hypokinetic, akinetic, or dyskinetic during stress. In the presence of transmural necrosis, akinetic or dyskinetic segments do not improve during stress. However, in the presence of viable myocardium, hypokinetic, akinetic or dyskinetic segments show improved wall motion during stress. Hibernation can be detected by a biphasic response of initial improvement of wall motion at low stress level followed by decline at higher stress levels – a pattern which predicts wall motion improvement by revascularisation.

The most commonly used stressor in stress echocardiography is physical exercise on a bicycle or treadmill. Although exercise carries important information on symptoms and prognosis, many patients are not able to exercise or can only exercise submaximally. Therefore, pharmacological stress with infusion of either dobutamine or dipyridamole is a good and safe alternative for physical exercise. Dobutamine causes tachycardia, increased ventricular contractility, and increased myocardial oxygen demand via stimulation of adrenergic receptors. Dipyridamole induces wall motion abnormalities through reduced subendocardial flow supply secondary to inappropriate arteriolar vasodilatation and steal phenomenon. Atropine can be added to pharmacological stress to increase heart rate and improve sensitivity of the test. All stressors are considered equipotent in inducing ischaemic wall motion abnormalities in the presence of flow-limiting coronary artery stenosis. Therefore, the choice of stressor depends mainly on relative contraindications and the ability to achieve maximal stress response.

A standardised protocol is required to perform a safe stress echocardiography study that provides maximal diagnostic accuracy. Detailed protocols can be found in the references. A typical protocol can consist of graded infusions of dobutamine starting at 5 μg/kg/min and increasing at 3 min stages to 10, 20, 30, 40 μg/kg/min. Rest images are acquired first and they serve as the reference for comparison with stress images. Pharmacological stress allows continuous monitoring of wall motion during stress. Because scanning during physical exercise is difficult, stress images are obtained as quickly as possible after exercise is performed, otherwise recovery of reversible wall motion abnormalities after stress, which can occur within minutes, can result in reduced the sensitivity of the test.

Stress echocardiography is an accurate imaging method for the detection and localisation of CAD. The existing meta-analyses and multicentre trials have demonstrated that stress echocardiography is more accurate than an exercise ECG test in the detection of significant CAD. Depending on the meta-analysis, pooled sensitivity and specificity of exercise echocardiography are reported as 80–85% and 84–86% respectively. Normal stress echocardiography predicts a very low rate of major cardiac events (annual risk of death <1%). Therefore, it is safe to avoid invasive angiography in the presence of normal stress echocardiography.

The amount of existing evidence supporting the use of stress echocardiography for the detection of ischaemia is comparable to that of nuclear imaging techniques. Compared with nuclear imaging, stress echocardiography has the advantage of being more specific, because wall motion changes require ischaemia. Nuclear perfusion imaging is more sensitive, because perfusion abnormalities can be present even without true ischaemia. However, the sensitivity of stress echocardiography is also high for the detection of high-grade stenosis. The advantages of stress echocardiography are safety, availability and low cost. However, the success rate and diagnostic performance of echocardiography are dependent on the experience of the operator and the technique requires training. Image quality is adversely affected by high heart rate and breathing artefacts during stress. This can be especially challenging in patients with impairment of image quality due to obstructive lung disease, obesity or chest wall deformities. The use of an ultrasound contrast agent is recommended in selected patients with poor endocardial definition (i.e., two or more contiguous segments not visible on non-contrast images) to cause left ventricular cavity opacification and thus improve detection of the endocardial border motion.

Recent improvements in technology have aimed at quantification of global and regional wall motion abnormalities. Measurement of left ventricular volumes and, thus, global function can be done more accurately with 3 dimensional than 2 dimensional imaging. Tissue Doppler, strain imaging and speckle tracking have shown promise for objective quantification of regional wall motion in stress echocardiography. In addition to improving endocardial border detection, contrast-enhanced echocardiography combined with sensitive imaging techniques can be used for imaging of myocardial perfusion. Furthermore, using dedicated projections and Doppler echocardiography it is possible to visualise directly coronary artery flow and measure coronary flow reserve in response to vasodilator stimuli. The value of these technologies for routine clinical work remains to be seen in the future.

In summary, stress echocardiography is a well-established imaging technique for the diagnostic evaluation of patients with suspected or proven CAD. Regional wall motion abnormalities can reveal ischaemic and infarcted myocardial areas supplied by coronary arteries with flow-limiting stenosis. Furthermore, reversible and irreversible wall motion abnormalities can be differentiated.

Current clinical indications

Stress echocardiography can be considered for the detection of CAD as an alternative to exercise ECG especially in symptomatic patients with high intermediate, i.e. 65-85% pre-test likelihood of CAD where facilities, costs, and personnel resources allow. It is recommended in in patients with ECG abnormalities at rest that prevent accurate interpretation of ECG changes during stress. It is also useful in patients with non-conclusive exercise ECG but reasonable exercise tolerance, who do not have a high probability of significant coronary disease. Exercise stress testing is recommended rather than pharmacological stress whenever possible Stress echocardiography is also suitable for localisation of ischaemia in patients with prior revascularisation and to assess functional significance of intermediate lesions detected by invasive or computed tomography coronary angiography. Notably, resting echocardiogram is recommended for every patient with suspected CAD for exclusion of alternative causes of chest pain, identification of regional wall motion abnormalities suggestive of CAD as well as assessment of systolic and LV function.[11. Montalescot G, Sechtem U, Achenbach S, Andreotti F, Arden C, Budaj A, Bugiardini R, Crea F, Cuisset T, Di Mario C, Ferreira JR, Gersh BJ, Gitt AK, Hulot JS, Marx N, Opie LH, Pfisterer M, Prescott E, Ruschitzka F, Sabaté M, Senior R, Taggart DP, van der Wall EE, Vrints CJ; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines, Zamorano JL, Achenbach S, Baumgartner H, Bax JJ, Bueno H, Dean V, Deaton C, Erol C, Fagard R, Ferrari R, Hasdai D, Hoes AW, Kirchhof P, Knuuti J, Kolh P, Lancellotti P, Linhart A, Nihoyannopoulos P, Piepoli MF, Ponikowski P, Sirnes PA, Tamargo JL, Tendera M, Torbicki A, Wijns W, Windecker S; Document Reviewers, Knuuti J, Valgimigli M, Bueno H, Claeys MJ, Donner-Banzhoff N, Erol C, Frank H, Funck-Brentano C, Gaemperli O, Gonzalez-Juanatey JR, Hamilos M, Hasdai D, Husted S, James SK, Kervinen K, Kolh P, Kristensen SD, Lancellotti P, Maggioni AP, Piepoli MF, Pries AR, Romeo F, Rydén L, Simoons ML, Sirnes PA, Steg PG, Timmis A, Wijns W, Windecker S, Yildirir A, Zamorano JL. 2013 ESC guidelines on the management of stable coronary artery disease: the Task Force on the management of stable coronary artery disease of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2949-3003.

This paper includes diagnostic algorithms and sets out guidelines for the application of non-invasive testing for evaluating the likelihood of obstructive coronary artery disease in patients with stable angina, 22. Windecker S, Kolh P, Alfonso F, Collet JP, Cremer J, Falk V, Filippatos G, Hamm C, Head SJ, Jüni P, Kappetein AP, Kastrati A, Knuuti J, Landmesser U, Laufer G, Neumann FJ, Richter DJ, Schauerte P, Sousa Uva M, Stefanini GG, Taggart DP, Torracca L, Valgimigli M, Wijns W, Witkowski A. 2014 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization: The Task Force on Myocardial Revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS)Developed with the special contribution of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI). Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2541-619.

Guidelines for applying non-invasive imaging tech¬niques in diagnostic algorithms for evaluating the like¬lihood of obstructive coronary artery disease in patients with stable angina, 2727. Sicari R, Nihoyannopoulos P, Evangelista A, Kasprzak J, Lancellotti P, Poldermans D, Voigt JU, Zamorano JL; European Association of Echocardiography. Stress echocardiography expert consensus statement: European Association of Echocardiography (EAE) (a registered branch of the ESC). Eur J Echocardiogr. 2008;9:415-37.

Practice guidelines and review of evidence for perform¬ing stress echocardiography in evaluation of coronary artery disease]

Myocardial perfusion SPECT imaging

Myocardial perfusion imaging with single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) has been part of clinical routine since the 1980’s [2828. Verberne HJ, Acampa W, Anagnostopoulos C, Ballinger J, Bengel F, De Bondt P, Buechel RR, Cuocolo A, van Eck-Smit BL, Flotats A, Hacker M, Hindorf C, Kaufmann PA, Lindner O, Ljungberg M, Lonsdale M, Manrique A, Minarik D, Scholte AJ, Slart RH, Trägårdh E, de Wit TC, Hesse B; European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM). EANM procedural guidelines for radionuclide myocardial perfusion imaging with SPECT and SPECT/CT: 2015 revision. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2015;42:1929-40.

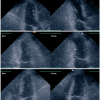

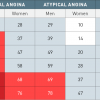

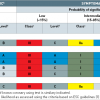

Practice guidelines and evidence for the use of myo¬cardial perfusion SPECT for the detection of coronary artery disease]. SPECT perfusion scintigraphy is performed to produce images of regional tracer uptake that reflects relative regional myocardial blood flow. Most commonly used tracers are 201-Thallium and Technetium-99m labelled sestamibi (99mTc-sestamibi) and tetrofosmin (99mTc tetrofosmin). After intravenous injection these radioactive tracers are taken up by myocardium and they emit gamma radiation from the target tissue which is detected with SPECT imaging. Myocardial ischaemia and old myocardial infarction are depicted by relatively reduced uptake of the tracer at rest and/or after stress as demonstrated in Figure 4 . Furthermore, increased uptake of myocardial perfusion agent in the lung fields identifies patients with severe and extensive CAD.

Usually, a regular exercise test (treadmill or bicycle) is used to stress the heart. Tracer injection is given 1 to 2 minutes before discontinuation of the test, which allows the tracer to be taken up by myocardium. Tracer uptake in ischaemic myocardium is lower than that in normal myocardium, but this relative difference is lost after rest. This is called a “reversible defect” and it is a hallmark of ischaemia. Irreversible defect (reduced or absent uptake of the tracer) represents myocardial scar. If the patient is unable to perform an adequate exercise test, myocardial perfusion imaging can underestimate the degree of coronary artery stenosis. On the other hand, increase in heart rate in patients with left bundle branch block or paced ventricular rhythm can lead to a reversible perfusion defect in interventricular septum falsely suggesting the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery territory ischaemia. In these cases a pharmacological stress test can be performed. Although true stress can be induced with agents like dobutamine, vasodilative agents such as dipyridamole and adenosine are preferred in clinical practice. Myocardial blood flow is increased 2.5-6 fold in normal myocardium and only 1-2 fold (depending on the degree of stenosis) in myocardium distal to a stenosed coronary artery. Thus although SPECT imaging does not allow quantitative analysis of blood flow, the relatively reduced or lower uptake of the tracer can reveal ischaemic myocardium distal to a stenosed coronary artery.

201-Thallium and 99m-Technetium labelled tracers have different physical properties and they are different in terms of myocardial uptake. 201-Thallium is readily taken up by myocardium - myocardial extraction during the first pass is high (approximately 88%). Thallium is rapidly redistributed after the first pass extraction. Therefore, stress-rest imaging can be performed with a single dose of 201-Thallium. Stress imaging is started approximately 10 minutes after Thallium injection and rest imaging 3-4 hours after the injection. First pass extraction of technetium-labelled tracers is lower than that of Thallium. However, both sestamibi and tetrofosmin bind almost irreversibly to myocardial mitochondria resulting in minimal myocardial washout. They also need separate tracer injection for stress and rest imaging. Optimally, rest and stress imaging would be performed on separate days but one-day protocols are commonly used. The dose in the second injection needs to be 3 times higher than in the first injection. Imaging is usually started 30-60 minutes after the injection. A minimum of 3-4 hours between injections is needed. Technetium-99m labelled tracers have higher photon energy than 201-Thallium and therefore there are fewer attenuation issues with 99mTc-sestamibi and 99mTc-tetrofosmin. In practice, this means fewer attenuation artefacts in patients with excessive amounts of subcutaneous tissue (large breasts, obese patients, etc). The radiation burden for patients is also significantly less with Technetium-99m labelled tracers compared to other tracers.

Imaging is usually performed with ECG gating, which allows assessment of both global and regional left ventricular function and left ventricular size. SPECT camera acquires data from multiple projections and this data is reconstructed to yield a 3D dataset. Finally, this dataset is used to reconstruct images along different axes of the left ventricle in a standardised manner - vertical long axis (VLA), horizontal long axis (HLA) and short axis (SA). Short axis slices can also be presented as a bull’s eye image. In addition to visual and qualitative analysis of the SPECT images, a quantitative analysis is recommended. The left ventricle is divided into 17 segments and in each segment the myocardial uptake of the tracer is graded from normal to absent. This helps to present the extent and severity of ischaemia or myocardial scar. In balanced 3-vessel coronary artery disease relative differences in tracer uptake can be very subtle and the extent of ischaemia can be underestimated. Fortunately, there are other signs such as transient ischaemic dilatation or increased lung uptake that can help to identify these patients.

In summary, SPECT perfusion provides a more sensitive and specific prediction of the presence of CAD than exercise ECG. Without correction for referral bias, the reported sensitivity of exercise SPECT when compared against invasive morphological imaging has generally ranged from 70% to 98% and specificity from 40% to 90%, with mean values in the range of 85–90% and 70–75%, depending on the meta-analysis. A newer SPECT technique with ECG gating has proved to be an accurate imaging technique for CAD in various patient populations including women, and diabetic and elderly patients.

Current clinical indications

SPECT perfusion imaging is indicated for the detection of myocardial ischaemia in patients with ECG abnormalities at rest that prevent accurate interpretation of ECG changes during stress. Perfusion imaging also provides useful information in patients with a non-conclusive exercise ECG but reasonable exercise tolerance and who do not have a high probability of significant coronary disease. Perfusion imaging can be considered as an alternative to exercise ECG where facilities, costs, and personnel resources allow, and especially in patients with high intermediate (65-85%) pretest probability of CAD. Perfusion imaging can be considered as an alternative to exercise ECG where facilities, costs, and personnel resources allow, and especially in patients with low pre-test probability of disease [11. Montalescot G, Sechtem U, Achenbach S, Andreotti F, Arden C, Budaj A, Bugiardini R, Crea F, Cuisset T, Di Mario C, Ferreira JR, Gersh BJ, Gitt AK, Hulot JS, Marx N, Opie LH, Pfisterer M, Prescott E, Ruschitzka F, Sabaté M, Senior R, Taggart DP, van der Wall EE, Vrints CJ; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines, Zamorano JL, Achenbach S, Baumgartner H, Bax JJ, Bueno H, Dean V, Deaton C, Erol C, Fagard R, Ferrari R, Hasdai D, Hoes AW, Kirchhof P, Knuuti J, Kolh P, Lancellotti P, Linhart A, Nihoyannopoulos P, Piepoli MF, Ponikowski P, Sirnes PA, Tamargo JL, Tendera M, Torbicki A, Wijns W, Windecker S; Document Reviewers, Knuuti J, Valgimigli M, Bueno H, Claeys MJ, Donner-Banzhoff N, Erol C, Frank H, Funck-Brentano C, Gaemperli O, Gonzalez-Juanatey JR, Hamilos M, Hasdai D, Husted S, James SK, Kervinen K, Kolh P, Kristensen SD, Lancellotti P, Maggioni AP, Piepoli MF, Pries AR, Romeo F, Rydén L, Simoons ML, Sirnes PA, Steg PG, Timmis A, Wijns W, Windecker S, Yildirir A, Zamorano JL. 2013 ESC guidelines on the management of stable coronary artery disease: the Task Force on the management of stable coronary artery disease of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2949-3003.

This paper includes diagnostic algorithms and sets out guidelines for the application of non-invasive testing for evaluating the likelihood of obstructive coronary artery disease in patients with stable angina, 22. Windecker S, Kolh P, Alfonso F, Collet JP, Cremer J, Falk V, Filippatos G, Hamm C, Head SJ, Jüni P, Kappetein AP, Kastrati A, Knuuti J, Landmesser U, Laufer G, Neumann FJ, Richter DJ, Schauerte P, Sousa Uva M, Stefanini GG, Taggart DP, Torracca L, Valgimigli M, Wijns W, Witkowski A. 2014 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization: The Task Force on Myocardial Revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS)Developed with the special contribution of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI). Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2541-619.

Guidelines for applying non-invasive imaging tech¬niques in diagnostic algorithms for evaluating the like¬lihood of obstructive coronary artery disease in patients with stable angina, 2828. Verberne HJ, Acampa W, Anagnostopoulos C, Ballinger J, Bengel F, De Bondt P, Buechel RR, Cuocolo A, van Eck-Smit BL, Flotats A, Hacker M, Hindorf C, Kaufmann PA, Lindner O, Ljungberg M, Lonsdale M, Manrique A, Minarik D, Scholte AJ, Slart RH, Trägårdh E, de Wit TC, Hesse B; European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM). EANM procedural guidelines for radionuclide myocardial perfusion imaging with SPECT and SPECT/CT: 2015 revision. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2015;42:1929-40.

Practice guidelines and evidence for the use of myo¬cardial perfusion SPECT for the detection of coronary artery disease].

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging cardiovascular MR has become an important tool for investigating the structure and function of the cardiovascular system [2929. Hundley WG, Bluemke DA, Finn JP, Flamm SD, Fogel MA, Friedrich MG, Ho VB, Jerosch-Herold M, Kramer CM, Manning WJ, Patel M, Pohost GM, Stillman AE, White RD, Woodard PK. ACCF/ACR/AHA/NASCI/SCMR 2010 expert consensus document on cardiovascular magnetic resonance: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Expert Consensus Documents. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010 Jun 8;55(23):2614-62.

Evidence and guidelines for the application of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in the detection of coro¬nary artery disease]. The strength of cardiovascular MR is based on its high spatial and temporal resolution as well as the high blood-tissue contrast ( Figure 5). In contrast to echocardiography, MRI is largely user-independent and does not suffer substantially from variations in image quality. It has no slice-orientation restrictions and its three-dimensional nature enables direct calculation of ventricular volumes without the need for using geometrical models. Cardiac MR can detect myocardial ischemia by assessing both myocardial perfusion and wall motion abnormalities in response to stress [3030. Hendel RC, Friedrich MG, Schulz-Menger J, Zemmrich C, Bengel F, Berman DS, Camici PG, Flamm SD, Le Guludec D, Kim R, Lombardi M, Mahmarian J, Sechtem U, Nagel E. CMR First-Pass Perfusion for Suspected Inducible Myocardial Ischemia. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9:1338-1348. ].

Similar to stress echocardiography, cardiac MR can detect myocardial ischemia accurately based on the detection of wall motion abnormalities that develop in response to dobutamine stress. Perfusion imaging is often preferred perhaps due to concerns related to dobutamine administration in the scanner, although major complications have been reported very rarely.

Cardiac perfusion MR is performed at rest and peak vasodilator stress (eg. adenosine, dipyridamole or regadenoson) following the bolus administration of gadolinium contrast agent. On first pass perfusion regions of myocardial ischemia are relatively hypoperfused, resulting in a reduced or delayed peak in the myocardial signal intensity. Reversible perfusion defects can then be differentiated from areas of myocardial infarction, identified on rest perfusion or late gadolinium enhancement. Diagnostic value of cardiac MR perfusion imaging has been tested in multiple large clinical trials that show high diagnostic accuracy [3030. Hendel RC, Friedrich MG, Schulz-Menger J, Zemmrich C, Bengel F, Berman DS, Camici PG, Flamm SD, Le Guludec D, Kim R, Lombardi M, Mahmarian J, Sechtem U, Nagel E. CMR First-Pass Perfusion for Suspected Inducible Myocardial Ischemia. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9:1338-1348. ]. A large meta-analysis demonstrated pooled sensitivity of 89% and specificity of 76% for the detection of obstructive CAD on invasive coronary angiography [3131. Jaarsma C, Leiner T, Bekkers SC, Crijns HJ, Wildberger JE, Nagel E, Nelemans PJ, Schalla S. Diagnostic performance of noninvasive myocardial perfusion imaging using single-photon emission computed tomography, cardiac magnetic resonance, and positron emission tomography imaging for the detection of obstructive coronary artery disease: A meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:1719-1728. ]. Comparative studies have indicated similar or better accuracy as compared with SPECT perfusion imaging [3232. Greenwood JP, Maredia N, Younger JF, Brown JM, Nixon J, Everett CC, Bijsterveld P, Ridgway JP, Radjenovic A, Dickinson CJ, Ball SG, Plein S. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance and single-photon emission computed tomography for diagnosis of coronary heart disease (CE-MARC): a prospective trial. Lancet. 2012;379:453-60. , 3333. Schwitter J, Wacker CM, Wilke N, Al-Saadi N, Sauer E, Huettle K, Schönberg SO, Luchner A, Strohm O, Ahlstrom H, Dill T, Hoebel N, Simor T; MR-IMPACT Investigators. MR-IMPACT II: Magnetic Resonance Imaging for Myocardial Perfusion Assessment in Coronary artery disease Trial: perfusion-cardiac magnetic resonance vs. single-photon emission computed tomography for the detection of coronary artery disease: a comparative multicentre, multivendor trial. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:775-81. ]. Several studies have demonstrated the prognostic value of cardiac MR, in particular a negative cardiac MR stress perfusion test is associated with an excellent prognosis (<1% annual rate of myocardial infarction or cardiovascular death) [3030. Hendel RC, Friedrich MG, Schulz-Menger J, Zemmrich C, Bengel F, Berman DS, Camici PG, Flamm SD, Le Guludec D, Kim R, Lombardi M, Mahmarian J, Sechtem U, Nagel E. CMR First-Pass Perfusion for Suspected Inducible Myocardial Ischemia. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9:1338-1348. ]. A recent randomized CE-MARC II trial demonstrated that compared with standard care the use of ischemia testing with cardiac MR or with SPECT resulted in lower number of negative invasive coronary angiographies in evaluation of patients with stable chest pain [3434. Greenwood JP, Ripley DP, Berry C, McCann GP, Plein S, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Dall’Armellina E, Prasad A, Bijsterveld P, Foley JR, Mangion K, Sculpher M, Walker S, Everett CC, Cairns DA, Sharples LD, Brown JM; CE-MARC 2 Investigators. Effect of Care Guided by Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, Myocardial Perfusion Scintigraphy, or NICE Guidelines on Subsequent Unnecessary Angiography Rates: The CE-MARC 2 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016;316:1051-60. ]

Cardiac MR provides characterization of myocardial tissue beyond perfusion. The presence of persistent gadolinium contrast enhancement on delayed MR imaging is a sensitive technique for the detection of scars of prior infarction in the left ventricle myocardium ( Figure 5.). This is based on distribution of gadolinium in the interstitial space and its slower wash out from regions of fibrosis or scarring than areas of normal myocardium. Increased signal is therefore observed in these areas when imaging is performed at delayed time points. Subendocardial MI has been detected in 17% of patients with suspected ischemic heart disease, but without a previous diagnosis of MI [3535. Schelbert EB, Cao JJ, Sigurdsson S, Aspelund T, Kellman P, Aletras AH, Dyke CK, Thorgeirsson G, Eiriksdottir G, Launer LJ, Gudnason V, Harris TB, Arai AE. Prevalence and prognosis of unrecognized myocardial infarction determined by cardiac magnetic resonance in older adults. JAMA. 2012;308:890-6. ]. Importantly, the presence of myocardial infarction in gadolinium late enhancement MR has been a strong predictor of an adverse prognosis. Thus, cardiac MR may be particularly useful in assessment of patients with severe coronary artery disease when additional information related to cardiac function and myocardial viability can aid decision making.

Different pathologies demonstrate different patterns of scarring and late gadolinium enhancement. Previous MI is associated with subendocardial enhancement, whereas the absence or linear mid-wall enhancement pattern is typical in dilated cardiomyopathy. Thus, cardiac MR with late gadolinium enhancement can aid in differentiation between ischemic and dilated cardiomyopathy. In addition to scar, cardiac MR can provide tissue characterization with the ability to demonstrate myocardial necrosis, edema, haemorrhage, microvascular obstruction, and left ventricular thrombus. Native T2 weighted cardiovascular MR may be useful for differential diagnostics between acute coronary syndrome and other causes of acute chest pain such as Tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy and myocarditis. Novel T1 mapping techniques can identify and provide quantitative estimates of diffuse, interstitial fibrosis in the myocardium remote from MI.

MR imaging is a safe method for the patient. This imaging technique completely avoids ionising radiation exposure in contrast to nuclear or x-ray-based techniques. Gadolinium based contrast media are widely used in radiological practice; with an excellent safety profile (the incidence of acute adverse reactions is 0.1% to 0.2%). However, they should be avoided, if possible, in patients with advanced renal dysfunction (glomerular filtration rate <30 ml/min/1.73 m2), in who the rare but serious complication of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis has been reported. One of the most important safety issues for cardiovascular MR is to avoid ferromagnetic materials near the scanner, as they may become hazardous flying objects. Most of the metallic implants such as orthopaedic prostheses, mechanical heart valves, coronary stents and sternal sutures are MRI safe since these are not ferromagnetic. Patients with pacemakers, implantable cardioverter defibrillators, retained permanent pacemaker leads and other electronic implants are currently not scanned. Cerebrovascular clips are often contraindicated but their MR suitability can be confirmed by a specialist. If necessary, a device’s MRI compatibility can be checked by way of the following link (>www.mrisafety.com). Claustrophobia may preclude examination in some patients.

Current clinical indications

Stress cardiovascular MR imaging indications are generally the same as with stress echocardiography or SPECT perfusion imaging. Cardiovascular MR can be used to detect myocardial ischaemia in patients with ECG abnormalities at rest that prevent accurate interpretation of ECG changes during stress. Also, cardiovascular MR imaging provides useful information in patients with a non-conclusive exercise ECG but reasonable exercise tolerance and who do not have a high probability of significant coronary disease. [11. Montalescot G, Sechtem U, Achenbach S, Andreotti F, Arden C, Budaj A, Bugiardini R, Crea F, Cuisset T, Di Mario C, Ferreira JR, Gersh BJ, Gitt AK, Hulot JS, Marx N, Opie LH, Pfisterer M, Prescott E, Ruschitzka F, Sabaté M, Senior R, Taggart DP, van der Wall EE, Vrints CJ; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines, Zamorano JL, Achenbach S, Baumgartner H, Bax JJ, Bueno H, Dean V, Deaton C, Erol C, Fagard R, Ferrari R, Hasdai D, Hoes AW, Kirchhof P, Knuuti J, Kolh P, Lancellotti P, Linhart A, Nihoyannopoulos P, Piepoli MF, Ponikowski P, Sirnes PA, Tamargo JL, Tendera M, Torbicki A, Wijns W, Windecker S; Document Reviewers, Knuuti J, Valgimigli M, Bueno H, Claeys MJ, Donner-Banzhoff N, Erol C, Frank H, Funck-Brentano C, Gaemperli O, Gonzalez-Juanatey JR, Hamilos M, Hasdai D, Husted S, James SK, Kervinen K, Kolh P, Kristensen SD, Lancellotti P, Maggioni AP, Piepoli MF, Pries AR, Romeo F, Rydén L, Simoons ML, Sirnes PA, Steg PG, Timmis A, Wijns W, Windecker S, Yildirir A, Zamorano JL. 2013 ESC guidelines on the management of stable coronary artery disease: the Task Force on the management of stable coronary artery disease of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2949-3003.

This paper includes diagnostic algorithms and sets out guidelines for the application of non-invasive testing for evaluating the likelihood of obstructive coronary artery disease in patients with stable angina, 22. Windecker S, Kolh P, Alfonso F, Collet JP, Cremer J, Falk V, Filippatos G, Hamm C, Head SJ, Jüni P, Kappetein AP, Kastrati A, Knuuti J, Landmesser U, Laufer G, Neumann FJ, Richter DJ, Schauerte P, Sousa Uva M, Stefanini GG, Taggart DP, Torracca L, Valgimigli M, Wijns W, Witkowski A. 2014 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization: The Task Force on Myocardial Revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS)Developed with the special contribution of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI). Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2541-619.

Guidelines for applying non-invasive imaging tech¬niques in diagnostic algorithms for evaluating the like¬lihood of obstructive coronary artery disease in patients with stable angina, 2929. Hundley WG, Bluemke DA, Finn JP, Flamm SD, Fogel MA, Friedrich MG, Ho VB, Jerosch-Herold M, Kramer CM, Manning WJ, Patel M, Pohost GM, Stillman AE, White RD, Woodard PK. ACCF/ACR/AHA/NASCI/SCMR 2010 expert consensus document on cardiovascular magnetic resonance: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Expert Consensus Documents. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010 Jun 8;55(23):2614-62.

Evidence and guidelines for the application of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in the detection of coro¬nary artery disease].

Positron emission tomography (PET)

Positron emission tomography (PET) represents an advanced scintigraphic imaging technology. PET allows non-invasive functional assessment of myocardial perfusion, substrate metabolism and cardiac innervation and receptors as well as gene expression in vivo and it has contributed significantly to advancing our understanding of heart physiology and pathophysiology. Recent technical developments and increased availability of techniques have also facilitated the use of PET in clinical cardiology.

There are several technical features that make PET a strong technology for the non-invasive evaluation of cardiac physiology. The sensitivity and contrast resolution of PET are exceptionally high. The spatial resolution is high enough for cardiac imaging and it is independent of depth. The temporal resolution (in the order of seconds) is high enough to enable imaging of physiological and metabolic processes. Finally, these processes can be measured in absolute quantitative units.

Positron emission tomography is a validated and highly reproducible method to provide regional quantification of myocardial blood flow at a microcirculatory level under rest and stress conditions. The three main tracers used in the imaging of perfusion are 15-oxygen-labelled water, 13-nitrogen-labelled ammonia and the generator-produced 82-Rubidium. Each of these tracers has specific advantages and limitations but the discussion of these is beyond this review.

The imaging protocol length depends on the tracer used. Typical perfusion imaging takes from 4 to 20 minutes. Dynamic scan is required for quantitative perfusion measurement. After the decay of tracer, the stress study is followed using pharmacological stressors such as adenosine, dipyridamole or dobutamine. Due to short half-life of the PET tracers the stress study can be performed practically without delay after the rest study. The total time required for a whole study session depends on the tracer used but typically the whole session can be finished in 30 minutes. Since the recent PET systems are capable of list-mode acquisition, the data can be collected at the same time as ECG-gated mode which allows the assessment of regional and global left ventricular wall motion from the same scan data.

The studies with myocardial perfusion PET have reported excellent diagnostic capabilities in the detection of coronary artery disease. In recent meta-analyses of PET in the diagnosis of CAD defined as ≥50% or ≥70% stenosis on invasive coronary angiography, PET demonstrated a sensitivites of 84-90% and a specificities of 81-88% [3131. Jaarsma C, Leiner T, Bekkers SC, Crijns HJ, Wildberger JE, Nagel E, Nelemans PJ, Schalla S. Diagnostic performance of noninvasive myocardial perfusion imaging using single-photon emission computed tomography, cardiac magnetic resonance, and positron emission tomography imaging for the detection of obstructive coronary artery disease: A meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:1719-1728. , 3636. Mc Ardle BA, Dowsley TF, deKemp RA, Wells GA, Beanlands RS. Does rubidium-82 pet have superior accuracy to spect perfusion imaging for the diagnosis of obstructive coronary disease?: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:1828-1837. ]. The comparison of PET perfusion imaging techniques have also favoured PET against SPECT [3131. Jaarsma C, Leiner T, Bekkers SC, Crijns HJ, Wildberger JE, Nagel E, Nelemans PJ, Schalla S. Diagnostic performance of noninvasive myocardial perfusion imaging using single-photon emission computed tomography, cardiac magnetic resonance, and positron emission tomography imaging for the detection of obstructive coronary artery disease: A meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:1719-1728. , 3636. Mc Ardle BA, Dowsley TF, deKemp RA, Wells GA, Beanlands RS. Does rubidium-82 pet have superior accuracy to spect perfusion imaging for the diagnosis of obstructive coronary disease?: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:1828-1837. ]. Large clinical registries including thousands of patients with suspected CAD have recently confirmed that the extent and severity of ischemia and scar on PET perfusion imaging provide incremental risk estimates of future cardiac and all-cause death, compared with traditional risk factors [3737. Dorbala S, Di Carli MF, Beanlands RS, Merhige ME, Williams BA, Veledar E, Chow BJ, Min JK, Pencina MJ, Berman DS, Shaw LJ. Prognostic value of stress myocardial perfusion positron emission tomography: Results from a multicenter observational registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:176-184. , 3838. Williams BA, Dorn JM, LaMonte MJ, Donahue RP, Trevisan M, Leonard DA, Greene RS, Merhige ME. Evaluating the prognostic value of positron-emission tomography myocardial perfusion imaging using automated software to calculate perfusion defect size. Clin Cardiol. 2012;35:E14-21. ].

A unique characteristic of PET which can further improve accuracy, especially in patients with multivessel disease as well as monitoring therapeutic effects of cardiac disease, is that myocardial blood flow can be measured in absolute units (ml/g/min) [3939. Saraste A, Kajander S, Han C, Nesterov SV, Knuuti J. Pet: Is myocardial flow quantification a clinical reality?. J Nucl Cardiol. 2012;19:1044-1059. ]. Several studies have described diagnostic benefits of absolute perfusion analysis compared with relative perfusion assessment [4040. Stuijfzand WJ, Uusitalo V, Kero T, Danad I, Rijnierse MT, Saraste A, Raijmakers PG, Lammertsma AA, Harms HJ, Heymans MW, Huisman MC, Marques KM, Kajander SA, Pietilä M, Sörensen J, van Royen N, Knuuti J, Knaapen P. Relative flow reserve derived from quantitative perfusion imaging may not outperform stress myocardial blood flow for identification of hemodynamically significant coronary artery disease. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8(1). , 4141. Joutsiniemi E, Saraste A, Pietilä M, Mäki M, Kajander S, Ukkonen H, Airaksinen J, Knuuti J. Absolute flow or myocardial flow reserve for the detection of significant coronary artery disease?. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;15:659-65. , 4242. Danad I, Raijmakers PG, Harms HJ, van Kuijk C, van Royen N, Diamant M, Lammertsma AA, Lubberink M, van Rossum AC, Knaapen P. Effect of cardiac hybrid ¹⁵O-water PET/CT imaging on downstream referral for invasive coronary angiography and revascularization rate. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;15:170-9. ].

Current clinical indications