Summary

The only specific treatment after coronary angioplasty is the dual antiplatelet therapy, comprising an association of aspirin and a P2Y12 receptor inhibitor (clopidogrel or prasugrel). The duration of this association depends on the type of stent used (BMS or DES), the initial clinical presentation (stable angina vs ACS), and the estimated thrombotic and bleeding risks of the patient. A reduction in the duration of DAPT to one-three months according to the type of stent (BMS or latest generation DES) can be discussed in stable coronary artery disease. Conversely, after ACS, 12 months of DAPT remains the rule, but this duration can be extended longer term depending on the patient characteristics, and exact DAPT duration should be discussed on a case-by-case basis.

After PCI, as for all patients with established coronary atherosclerosis, patients should receive “optimal medical therapy” to slow progression of atherosclerosis and to avoid atherothrombotic complications. Thus, the control of risk factors with lifestyle measures, and the use of drugs of proven efficacy in terms of prevention of atherosclerosis and its complications should be reinforced.

Female gender, older age, diabetes, renal dysfunction or need for oral anticoagulation, the site of the treated lesion and the type of procedure all impact considerably on the modalities of follow-up and treatment after PCI.

Introduction: PCI and specificlesion and patient subsets

Advances in the pharmacological and technical environment for PCI, particularly the use of stents, have contributed to the spectacular development of PCI in recent years in terms of safety and efficacy. Nonetheless, the appropriate patient follow-up and medical therapy after the procedure remain major issues. PCI only yields a benefit in clinical terms if it is accompanied by the whole spectrum of lifestyle measures, medical follow-up and pharmacological therapy, both specific to PCI, and more generally, recommended for patients with atheromatous disease.

This chapter will describe the recommended approach to patient follow-up and secondary prevention therapy after PCI. There are general recommendations that can be applied to the majority of patients, but there are also a myriad of special situations that may require specific measures, depending, for example, on the characteristics or comorbidities presented by the patient, the coronary anatomy, the site of angioplasty, or the type of technique used during PCI.

Non specific secondary prevention after PCI

Coronary revascularisation can be seen as a consequence of the failure of primary or secondary prevention, and justifies optimization of anti-atherosclerotic therapy. In addition to appropriate pharmacological treatment to prevent further progression of atherosclerosis, a number of specific treatments are necessary after PCI.

MEASURES NOT-SPECIFIC TO PCI

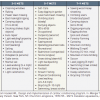

Current recommendations for lifestyle modifications, risk factor control, medical therapy to prevent progression of atherosclerosis, stabilise the plaque, restore endothelial function or prevent thrombosis are all applicable after PCI. These measures are commonly known as “optimal medical treatment” (OMT) and are designed to reduce mortality and morbidity, while maintaining a favourable cost-efficacy profile [11. Hamm CW, Bassand JP, Agewall S, Bax J, Boersma E, Bueno H, Caso P, Dudek D, Gielen S, Huber K, Ohman M, Petrie MC, Sonntag F, Uva MS, Storey RF, Wijns W, Zahger D: ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute coronary syndromes (ACS) in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2011;32:2999-3054. , 22. Steg PG, James SK, Atar D, Badano LP, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, Borger MA, Di Mario C, Dickstein K, Ducrocq G, Fernandez-Aviles F, Gershlick AH, Giannuzzi P, Halvorsen S, Huber K, Juni P, Kastrati A, Knuuti J, Lenzen MJ, Mahaffey KW, Valgimigli M, van ’t Hof A, Widimsky P, Zahger D: ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2569-619. ]. OMT associates lifestyle measures, strict risk factor control, and medical therapy with a combination of aspirin, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI), beta-blockers and statins ( Figure 1 ).

- Aspirin should be prescribed at a dose of 75 to 100 mg/day, for life. Higher doses do not yield any demonstrable additional benefit, whereas they expose the patient to a higher risk of gastro-intestinal side effects or bleeding [33. Collaborative meta-analysis of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high risk patients. BMJ. 2002;324:71-86. , 44. Montalescot G, Sechtem U, Achenbach S, Andreotti F, Arden C, Budaj A, Bugiardini R, Crea F, Cuisset T, Di Mario C, Ferreira JR, Gersh BJ, Gitt AK, Hulot JS, Marx N, Opie LH, Pfisterer M, Prescott E, Ruschitzka F, Sabate M, Senior R, Taggart DP, van der Wall EE, Vrints CJ, Zamorano JL, Baumgartner H, Bax JJ, Bueno H, Dean V, Deaton C, Erol C, Fagard R, Ferrari R, Hasdai D, Hoes AW, Kirchhof P, Knuuti J, Kolh P, Lancellotti P, Linhart A, Nihoyannopoulos P, Piepoli MF, Ponikowski P, Sirnes PA, Tamargo JL, Tendera M, Torbicki A, Wijns W, Windecker S, Valgimigli M, Claeys MJ, Donner-Banzhoff N, Frank H, Funck-Brentano C, Gaemperli O, Gonzalez-Juanatey JR, Hamilos M, Husted S, James SK, Kervinen K, Kristensen SD, Maggioni AP, Pries AR, Romeo F, Ryden L, Simoons ML, Steg PG, Timmis A, Yildirir A: 2013 ESC guidelines on the management of stable coronary artery disease: the Task Force on the management of stable coronary artery disease of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2949-3003. , 55. Peters RJ, Mehta SR, Fox KA, Zhao F, Lewis BS, Kopecky SL, Diaz R, Commerford PJ, Valentin V, Yusuf S: Effects of aspirin dose when used alone or in combination with clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes: observations from the Clopidogrel in Unstable angina to prevent Recurrent Events (CURE) study. Circulation. 2003;108:1682-7. ].

- Long term dual antiplatelet therapy in addition to low dose aspirin, such as ticagrelor, at a dose of 90mg or 60mg, twice a day, should be considered in stable patients with previous MI, age over 50 and additional risk factor, and without bleeding risk [66. Bonaca MP, Bhatt DL, Cohen M, Steg PG, Storey RF, Jensen EC, Magnani G, Bansilal S, Fish MP, Im K, Bengtsson O, Ophuis TO, Budaj A, Theroux P, Ruda M, Hamm C, Goto S, Spinar J, Nicolau JC, Kiss RG, Murphy SA, Wiviott SD, Held P, Braunwald E, Sabatine MS: Long-Term Use of Ticagrelor in Patients with Prior Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med. 2015. ].

- ACEI (or angiotensin receptor antagonists, in case of ACEI intolerance) are recommended in all situations after PCI. In patients with normal left ventricular (LV) function, ramipril at a dose of 10mg/day is indicated in diabetic patients who also have one other risk factor [77. Yusuf S, Sleight P, Pogue J, Bosch J, Davies R, Dagenais G: Effects of an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, ramipril, on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients. The Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:145-53. ]. In patients considered to be at “low risk”, without diabetes and with preserved LV function, perindopril at a dose of 8mg /day is recommended [44. Montalescot G, Sechtem U, Achenbach S, Andreotti F, Arden C, Budaj A, Bugiardini R, Crea F, Cuisset T, Di Mario C, Ferreira JR, Gersh BJ, Gitt AK, Hulot JS, Marx N, Opie LH, Pfisterer M, Prescott E, Ruschitzka F, Sabate M, Senior R, Taggart DP, van der Wall EE, Vrints CJ, Zamorano JL, Baumgartner H, Bax JJ, Bueno H, Dean V, Deaton C, Erol C, Fagard R, Ferrari R, Hasdai D, Hoes AW, Kirchhof P, Knuuti J, Kolh P, Lancellotti P, Linhart A, Nihoyannopoulos P, Piepoli MF, Ponikowski P, Sirnes PA, Tamargo JL, Tendera M, Torbicki A, Wijns W, Windecker S, Valgimigli M, Claeys MJ, Donner-Banzhoff N, Frank H, Funck-Brentano C, Gaemperli O, Gonzalez-Juanatey JR, Hamilos M, Husted S, James SK, Kervinen K, Kristensen SD, Maggioni AP, Pries AR, Romeo F, Ryden L, Simoons ML, Steg PG, Timmis A, Yildirir A: 2013 ESC guidelines on the management of stable coronary artery disease: the Task Force on the management of stable coronary artery disease of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2949-3003. , 88. Fox KM: Efficacy of perindopril in reduction of cardiovascular events among patients with stable coronary artery disease: randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial (the EUROPA study). Lancet. 2003;362:782-8. ]. The dosage of ACEI should be adapted to patient tolerance in terms of blood pressure and biology, with the aim, however, of attaining the aforementioned doses, which have been proven efficacious in these populations.

- Beta-blockers are indicated to control angina during exercise, but are also recommended for at least the first year after an infarction [99. Yusuf S, Wittes J, Friedman L: Overview of results of randomized clinical trials in heart disease. I. Treatments following myocardial infarction. JAMA. 1988;260:2088-93. ]. The beneficial effect of beta-blockers in stable patients is less well established [1010. Pepine CJ, Cohn PF, Deedwania PC, Gibson RS, Handberg E, Hill JA, Miller E, Marks RG, Thadani U: Effects of treatment on outcome in mildly symptomatic patients with ischemia during daily life. The Atenolol Silent Ischemia Study (ASIST). Circulation. 1994;90:762-8. ], except in patients with LV dysfunction, in whom metaprolol, bisoprolol and carvedilol are recommended [1111. Fox K, Garcia MA, Ardissino D, Buszman P, Camici PG, Crea F, Daly C, De Backer G, Hjemdahl P, Lopez-Sendon J, Marco J, Morais J, Pepper J, Sechtem U, Simoons M, Thygesen K, Priori SG, Blanc JJ, Budaj A, Camm J, Dean V, Deckers J, Dickstein K, Lekakis J, McGregor K, Metra M, Osterspey A, Tamargo J, Zamorano JL: Guidelines on the management of stable angina pectoris: executive summary: The Task Force on the Management of Stable Angina Pectoris of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1341-81. ]. In case of beta-blocker intolerance, verapamil can be prescribed [1212. Effect of verapamil on mortality and major events after acute myocardial infarction (the Danish Verapamil Infarction Trial II--DAVIT II). Am J Cardiol. 1990;66:779-85. ]. In patients whose heart rate exceeds 70 bpm while under beta-blocker therapy, in sinus rhythm, ivabradine can be used as an anti-anginal agent, or to reduce incidence of cardiovascular events in case of systolic dysfunction [1313. Fox K, Ford I, Steg PG, Tendera M, Ferrari R: Ivabradine for patients with stable coronary artery disease and left-ventricular systolic dysfunction (BEAUTIFUL): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;372:807-16. ].

- Statins are recommended for all patients after PCI, irrespective of the initial level of LDL cholesterol [1414. MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol lowering with simvastatin in 20,536 high-risk individuals: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360:7-22. , 1515. Cannon CP, Steinberg BA, Murphy SA, Mega JL, Braunwald E: Meta-analysis of cardiovascular outcomes trials comparing intensive versus moderate statin therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:438-45. ]. High doses of statins were shown to slow, if not prevent progression of coronary atherosclerosis [1414. MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol lowering with simvastatin in 20,536 high-risk individuals: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360:7-22. , 1515. Cannon CP, Steinberg BA, Murphy SA, Mega JL, Braunwald E: Meta-analysis of cardiovascular outcomes trials comparing intensive versus moderate statin therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:438-45. , 1616. Nissen SE, Nicholls SJ, Sipahi I, Libby P, Raichlen JS, Ballantyne CM, Davignon J, Erbel R, Fruchart JC, Tardif JC, Schoenhagen P, Crowe T, Cain V, Wolski K, Goormastic M, Tuzcu EM: Effect of very high-intensity statin therapy on regression of coronary atherosclerosis: the ASTEROID trial. JAMA. 2006;295:1556-65. , 1717. Nissen SE, Tuzcu EM, Schoenhagen P, Brown BG, Ganz P, Vogel RA, Crowe T, Howard G, Cooper CJ, Brodie B, Grines CL, DeMaria AN: Effect of intensive compared with moderate lipid-lowering therapy on progression of coronary atherosclerosis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:1071-80. ] and must be used in the setting of acute coronary syndrome (ACS)[1818. Cannon CP: PROVE-IT TIMI 22 Study: potential effects on critical pathways for acute coronary syndrome. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2003;2:188-96. ] . Depending on the LDL level achieved with statin therapy, further lipid lowering drugs must be discussed, such as ezetimibe, since the IMPROVE-IT trial showed an addidtional benefit of lowering LDL cholesterol level below 0.7 g/L with ezetimibe [1919. Cannon CP: IMProved Reduction of Outcomes: Vytorin Efficacy International Trial (IMPROVE-IT). Presented at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions, Chicago. November 15–18, 2014. ].

- Treatments such as calcium channel blockers should be reserved for use as substitutes for beta-blocker therapy when these latter are not tolerated. Vitamins and antioxidants have not been shown to be beneficial after angioplasty, nor have omega-3 fatty acids. Finally, Cox-2 inhibitors should be avoided, as they predispose to accelerated development of atherosclerosis and arterial thrombosis. Similarly, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) inhibit the production of prostacyclin, although they have antiplatelet properties, and the dose of NSAIDs should be carefully adjusted to maintain a balance between the risk of stent thrombosis and the risk of bleeding complications.

Patients treated for ACS. A vast majority of patients undergoing PCI are submitted to this procedure in the context of ACS. This context of ACS impacts directly on the dose and duration of therapy. However, the association of aspirin and clopidogrel (or prasugrel or ticagrelor) is independent of the type of procedure or stent used, and must be prescribed for a minimum of one year after PCI. A randomised study showed that high dose atorvastatin therapy was more beneficial than lower dose statins, when initiated at the acute phase in patients submitted to PCI [2020. Gibson CM, Pride YB, Hochberg CP, Sloan S, Sabatine MS, Cannon CP: Effect of intensive statin therapy on clinical outcomes among patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention for acute coronary syndrome. PCI-PROVE IT: A PROVE IT-TIMI 22 (Pravastatin or Atorvastatin Evaluation and Infection Therapy-Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction 22) Substudy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:2290-5. ].

MEASURES SPECIFIC TO PCI

Certain aspects of secondary prevention are specific to patients undergoing PCI :

- Lifestyle measures : A PCI procedure is an ideal opportunity to underline the importance of secondary prevention, or to deliver this message for the first time in patients in whom coronary disease had not previously been manifest. In particular, it is important to underline the necessity of lifestyle measures (balanced diet including a high proportion of fruit and vegetables, stop smoking, reduce weight, regular exercise), correction of modifiable risk factors, and compliance with medical therapy ( Figure 2 )

- Medical therapy presents two specific features after PCI, namely association of antiplatelet agents, and therapeutic targets. Aspirin after PCI should be prescribed at doses corresponding to secondary prevention, namely 70 to 100mg/day. However, after PCI, aspirin must be associated with a platelet P2Y12 receptor antagonist, even in the absence of ACS. The duration of P2Y12 receptor inhibition depends on several factors, namely: the type of PCI procedure (particularly, the type of stent implanted, namely bare metal (BMS) or drug eluting stent (DES). With DES, the type of DES must also be taken in account as shorter DAPT durations after “new generation” DES have been demonstrated to be safe); the clinical situation (stable angina or ACS), and the bleeding risk. Generally, an association of aspirin and P2Y12 receptor antagonists should be prescribed for at least one year in case of bare metal stent implantation[2121. Schomig A, Neumann FJ, Kastrati A, Schuhlen H, Blasini R, Hadamitzky M, Walter H, Zitzmann-Roth EM, Richardt G, Alt E, Schmitt C, Ulm K: A randomized comparison of antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy after the placement of coronary-artery stents. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1084-9. ], and for 6 to 12 months in case of DES implantation [2222. Daemen J, Wenaweser P, Tsuchida K, Abrecht L, Vaina S, Morger C, Kukreja N, Juni P, Sianos G, Hellige G, van Domburg RT, Hess OM, Boersma E, Meier B, Windecker S, Serruys PW: Early and late coronary stent thrombosis of sirolimus-eluting and paclitaxel-eluting stents in routine clinical practice: data from a large two-institutional cohort study. Lancet. 2007;369:667-78. ], although longer prescriptions have been advocated [2323. Eisenstein EL, Anstrom KJ, Kong DF, Shaw LK, Tuttle RH, Mark DB, Kramer JM, Harrington RA, Matchar DB, Kandzari DE, Peterson ED, Schulman KA, Califf RM: Clopidogrel use and long-term clinical outcomes after drug-eluting stent implantation. JAMA. 2007;297:159-68. ]. In case of PCI in the setting of an ACS, any of three compounds (clopidogrel, prasugrel or ticagrelor) can be prescribed, whereas after PCI for stable angina, only clopidogrel is recommended. The use of other molecules can be envisaged if the response to clopidogrel is suboptimal. The particular importance of compliance with this treatment and its duration should be emphasised to the patient, because of the risk and potential severity of stent thrombosis [2424. McFadden EP, Stabile E, Regar E, Cheneau E, Ong AT, Kinnaird T, Suddath WO, Weissman NJ, Torguson R, Kent KM, Pichard AD, Satler LF, Waksman R, Serruys PW: Late thrombosis in drug-eluting coronary stents after discontinuation of antiplatelet therapy. Lancet. 2004;364:1519-21. , 2525. Ong AT, McFadden EP, Regar E, de Jaegere PP, van Domburg RT, Serruys PW: Late angiographic stent thrombosis (LAST) events with drug-eluting stents. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:2088-92. ]. After one year, regardless of the initial clinical presentation, prolongation of DAPT with either clopidogrel[2626. Mauri L, Kereiakes DJ, Yeh RW, Driscoll-Shempp P, Cutlip DE, Steg PG, Normand SL, Braunwald E, Wiviott SD, Cohen DJ, Holmes DR, Jr., Krucoff MW, Hermiller J, Dauerman HL, Simon DI, Kandzari DE, Garratt KN, Lee DP, Pow TK, Ver Lee P, Rinaldi MJ, Massaro JM: Twelve or 30 months of dual antiplatelet therapy after drug-eluting stents. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2155-66. ] or ticagrelor [2626. Mauri L, Kereiakes DJ, Yeh RW, Driscoll-Shempp P, Cutlip DE, Steg PG, Normand SL, Braunwald E, Wiviott SD, Cohen DJ, Holmes DR, Jr., Krucoff MW, Hermiller J, Dauerman HL, Simon DI, Kandzari DE, Garratt KN, Lee DP, Pow TK, Ver Lee P, Rinaldi MJ, Massaro JM: Twelve or 30 months of dual antiplatelet therapy after drug-eluting stents. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2155-66. ] should be discussed according to the patients characteristics.

The therapeutic targets of medical therapy should also be re-evaluated after PCI, particularly if progression of atherosclerotic disease is observed, or in patients who are already being treated. In this case, recommendations for lifestyle changes and risk factor control need to be reinforced, and ACEI should be prescribed at maximum recomended doses. Treatment with statins has a proven beneficial effect on coronary atherosclerosis [1616. Nissen SE, Nicholls SJ, Sipahi I, Libby P, Raichlen JS, Ballantyne CM, Davignon J, Erbel R, Fruchart JC, Tardif JC, Schoenhagen P, Crowe T, Cain V, Wolski K, Goormastic M, Tuzcu EM: Effect of very high-intensity statin therapy on regression of coronary atherosclerosis: the ASTEROID trial. JAMA. 2006;295:1556-65. , 2727. Nissen SE: Effect of intensive lipid lowering on progression of coronary atherosclerosis: evidence for an early benefit from the Reversal of Atherosclerosis with Aggressive Lipid Lowering (REVERSAL) trial. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96:61F-68F. ]. A slowing of atherosclerosis progression has been proven for LDL cholesterol levels less than 0.7 g/L, namely 0.55 g/L [1919. Cannon CP: IMProved Reduction of Outcomes: Vytorin Efficacy International Trial (IMPROVE-IT). Presented at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions, Chicago. November 15–18, 2014. ].

Specific follow-up after PCI

FOLLOW-UP OF PATIENTS AFTER PCI

The only difference between follow-up post-PCI and follow-up of patients in secondary prevention is that after PCI, physicians should keep watch for potential complications specific to PCI, either early or late. Early complications include arterial puncture site complications, mostly among patients who had PCI via a femoral access, anaemia or nephrotoxicity. In these situations, current European guidelines recommended clinical and biological follow-up 7 days after PCI [2828. Windecker S, Kolh P, Alfonso F, Collet JP, Cremer J, Falk V, Filippatos G, Hamm C, Head SJ, Juni P, Kappetein AP, Kastrati A, Knuuti J, Landmesser U, Laufer G, Neumann FJ, Richter DJ, Schauerte P, Sousa Uva M, Stefanini GG, Taggart DP, Torracca L, Valgimigli M, Wijns W, Witkowski A: 2014 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization: The Task Force on Myocardial Revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS)Developed with the special contribution of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI). Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2541-619. ].

CLINICAL EVALUATION AND FUNCTIONAL TESTS, APART FROM DETECTION OF RESTENOSIS

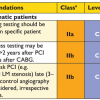

The benefit of routine exercise stress tests in asymptomatic patients has never been clearly demonstrated. Early evaluation after PCI makes it possible to quantify residual ischemia. Later evaluation can help detect incident ischemia resulting from the progression of atherosclerosis. Current recommendations for coronary revascularisation stipulate that lung perfusion scans or stress echocardiography should be prefered over bicycle ergometry exercise stress testing, which is less sensitive and less specific, particularly if revascularisation was incomplete [2828. Windecker S, Kolh P, Alfonso F, Collet JP, Cremer J, Falk V, Filippatos G, Hamm C, Head SJ, Juni P, Kappetein AP, Kastrati A, Knuuti J, Landmesser U, Laufer G, Neumann FJ, Richter DJ, Schauerte P, Sousa Uva M, Stefanini GG, Taggart DP, Torracca L, Valgimigli M, Wijns W, Witkowski A: 2014 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization: The Task Force on Myocardial Revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS)Developed with the special contribution of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI). Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2541-619. ]. At two years after PCI, ischaemia screening tests are of limited interest in asymptomatic patients and there is no clear recommandation for the timing of such tests (recommendation Grade IIb, level of evidence C) ( Figure 3 ).

Two specific events may can occur after PCI and justify close follow-up, namely stent thrombosis and restenosis.

- Stent thrombosis generally presents like ST segment elevation ACS. In patients who experience stent thrombosis while still under antiplatelet therapy, there is a likelihood that response to clopidogrel is suboptimal and these patients can potentially be considered as clopidogrel “non-responders” [2929. Buonamici P, Marcucci R, Migliorini A, Gensini GF, Santini A, Paniccia R, Moschi G, Gori AM, Abbate R, Antoniucci D: Impact of platelet reactivity after clopidogrel administration on drug-eluting stent thrombosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:2312-7. ]. Nevertheless, the major determinant of stent thrombosis is premature DAPT cessation. In the PARIS study, three main reasons for DAPT cessation were identified, namely, medical decision (discontinuation), temporary interruption (due to intermittant conditions such as need for surgery) and cessation without medical advice (disruption). DAPT disruption was associated with higher event rates, mostly due to stent thrombosis [3030. Mehran R, Baber U, Steg PG, Ariti C, Weisz G, Witzenbichler B, Henry TD, Kini AS, Stuckey T, Cohen DJ, Berger PB, Iakovou I, Dangas G, Waksman R, Antoniucci D, Sartori S, Krucoff MW, Hermiller JB, Shawl F, Gibson CM, Chieffo A, Alu M, Moliterno DJ, Colombo A, Pocock S: Cessation of dual antiplatelet treatment and cardiac events after percutaneous coronary intervention (PARIS): 2 year results from a prospective observational study. Lancet. 2013;382:1714-22. ]. Late stent thrombosis (i.e. occurring more than one year after PCI) has been described, with both bare-metal and active stents [2323. Eisenstein EL, Anstrom KJ, Kong DF, Shaw LK, Tuttle RH, Mark DB, Kramer JM, Harrington RA, Matchar DB, Kandzari DE, Peterson ED, Schulman KA, Califf RM: Clopidogrel use and long-term clinical outcomes after drug-eluting stent implantation. JAMA. 2007;297:159-68. ]. Prolonging DAPT beyond 12 months with clopidogrel [2626. Mauri L, Kereiakes DJ, Yeh RW, Driscoll-Shempp P, Cutlip DE, Steg PG, Normand SL, Braunwald E, Wiviott SD, Cohen DJ, Holmes DR, Jr., Krucoff MW, Hermiller J, Dauerman HL, Simon DI, Kandzari DE, Garratt KN, Lee DP, Pow TK, Ver Lee P, Rinaldi MJ, Massaro JM: Twelve or 30 months of dual antiplatelet therapy after drug-eluting stents. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2155-66. ] has been shown to reduce late stent thrombosis, particulary among patients treated with a paclitaxel eluting stent [3131. Garratt KN, Weaver WD, Jenkins RG, Pow TK, Mauri L, Kereiakes DJ, Winters KJ, Christen T, Allocco DJ, Lee DP: Prasugrel plus aspirin beyond 12 months is associated with improved outcomes after TAXUS Liberte paclitaxel-eluting coronary stent placement. Circulation. 2015;131:62-73. ].

- Restenosis is a different phenomenon than the initial atherosclerotic process, and arises from the injury caused to the arterial wall during PCI. It is characterised by neo-intimal proliferation of smooth muscle cells and extracellular matrix. After bare-metal stent implantation, this proliferation of restenosis tissue generally reduces the lumen diameter by approximately 1mm on average, but there are considerable variables between individuals, and between different lesion types. Thus, in 10 to 20% of cases, the restenosis can be extensive enough to reduce the vessel lumen significantly and cause myocardial ischemia.

- Clinical detection of restenosis consists in detecting myocardial ischemia in the territory of the revascularised artery. It is helpful to have a functional evaluation of angina as well as a baseline ECG dating from before PCI to serve as a starting point for later evaluation. Restenosis can be clinically suspected if signs of ischaemia (re-)appear, and in asymptomatic patients, by a positive result on functional tests (functional evaluation, stress echo, myocardial perfusion). Since restenosis appears gradually after PCI and can become clinically manifest between 2 and 9 months post-PCI, it is recommended to perform clinical evaluation at around 6 months. Beyond 9 months, there is usually no further proliferation, and the situation generally remains stable.

- Role of coronary angiography. If there is a clinical suspicion of restenosis, control angiography should be considered on a case-by-case basis, with a view to performing another revascularisation procedure where necessary, depending on the patient characteristics, functional tolerance, and the anatomy of the coronary arteries [2828. Windecker S, Kolh P, Alfonso F, Collet JP, Cremer J, Falk V, Filippatos G, Hamm C, Head SJ, Juni P, Kappetein AP, Kastrati A, Knuuti J, Landmesser U, Laufer G, Neumann FJ, Richter DJ, Schauerte P, Sousa Uva M, Stefanini GG, Taggart DP, Torracca L, Valgimigli M, Wijns W, Witkowski A: 2014 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization: The Task Force on Myocardial Revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS)Developed with the special contribution of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI). Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2541-619. ]. Systematic coronary angiography, in the absence of clinical manifestations of ischaemia, is not recommended, although it can be discussed in exceptional circumstances [3232. Schiele F: The ’angioplastically correct’ follow up strategy after stent implantation. Heart. 2001;85:363-4. ]. In addition to the invasive nature of the procedure, and the exposure to contrast medium and irradiation, it has been shwon that systematic control angiography leads to a twofold increase in revascularisation procedures [3333. Ruygrok PN, Melkert R, Morel MA, Ormiston JA, Bar FW, Fernandez-Aviles F, Suryapranata H, Dawkins KD, Hanet C, Serruys PW: Does angiography six months after coronary intervention influence management and outcome? Benestent II Investigators. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34:1507-11. , 3434. Serruys PW, van Hout B, Bonnier H, Legrand V, Garcia E, Macaya C, Sousa E, van der Giessen W, Colombo A, Seabra-Gomes R, Kiemeneij F, Ruygrok P, Ormiston J, Emanuelsson H, Fajadet J, Haude M, Klugmann S, Morel MA: Randomised comparison of implantation of heparin-coated stents with balloon angioplasty in selected patients with coronary artery disease (Benestent II). Lancet. 1998;352:673-81. ].

Specfic conditions for follow-up and secondary prevention after PCI: patient subsets.

Among the patient characteristics that can impact on follow-up and secondary prevention, several special populations need to be distinguished, namely female patients, elderly patients, diabetic patients, patients with renal insufficiency, and patients treated with oral anticoagulants.

WOMEN

Although women are under-represented in clinical trials, and the risk-benefit ratio of post-PCI therapies is less well established in female patients[3535. Melloni C, Berger JS, Wang TY, Gunes F, Stebbins A, Pieper KS, Dolor RJ, Douglas PS, Mark DB, Newby LK: Representation of women in randomized clinical trials of cardiovascular disease prevention. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3:135-42. ], there is nonetheless no justification for specific secondary prevention treatment in women after PCI [3636. Mosca L, Banka CL, Benjamin EJ, Berra K, Bushnell C, Dolor RJ, Ganiats TG, Gomes AS, Gornik HL, Gracia C, Gulati M, Haan CK, Judelson DR, Keenan N, Kelepouris E, Michos ED, Newby LK, Oparil S, Ouyang P, Oz MC, Petitti D, Pinn VW, Redberg RF, Scott R, Sherif K, Smith SC, Jr., Sopko G, Steinhorn RH, Stone NJ, Taubert KA, Todd BA, Urbina E, Wenger NK: Evidence-based guidelines for cardiovascular disease prevention in women: 2007 update. Circulation. 2007;115:1481-501. ]. Moreover aspirin, in secondary prevention, mediates its protective cardiovascular effect through a reduction in the rate of MI in men, but through a reduction in stroke in women [3737. Berger JS, Roncaglioni MC, Avanzini F, Pangrazzi I, Tognoni G, Brown DL: Aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events in women and men: a sex-specific meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2006;295:306-13. ]. Gender differences in the activity of cytochrome P450, responsible for the metabolism of many drugs, could explain the greater efficacy of certain molecules in women, although there are other differences which could account for this variability, such as the fact that women are, on average, older, more often diabetic and more frequently have renal dysfunction. The risk of bleeding complications could justify adjustment of therapy in women. The efficacy and safety of clopidogrel appear to be comparable in men and women [3838. Berger JS, Bhatt DL, Cannon CP, Chen Z, Jiang L, Jones JB, Mehta SR, Sabatine MS, Steinhubl SR, Topol EJ, Berger PB: The relative efficacy and safety of clopidogrel in women and men a sex-specific collaborative meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1935-45. ], although it has been shown that the rate of hyporesponders to clopidogrel is higher among female patients [3939. Jochmann N, Stangl K, Garbe E, Baumann G, Stangl V: Female-specific aspects in the pharmacotherapy of chronic cardiovascular diseases. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:1585-95. ]. Finally, the bleeding risk incurred by the association of aspirin and clopidogrel appears to be higher in women, although the difference does not reach statistical significance [3838. Berger JS, Bhatt DL, Cannon CP, Chen Z, Jiang L, Jones JB, Mehta SR, Sabatine MS, Steinhubl SR, Topol EJ, Berger PB: The relative efficacy and safety of clopidogrel in women and men a sex-specific collaborative meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1935-45. , 4040. Alexander KP, Chen AY, Newby LK, Schwartz JB, Redberg RF, Hochman JS, Roe MT, Gibler WB, Ohman EM, Peterson ED: Sex differences in major bleeding with glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors: results from the CRUSADE (Can Rapid risk stratification of Unstable angina patients Suppress ADverse outcomes with Early implementation of the ACC/AHA guidelines) initiative. Circulation. 2006;114:1380-7. , 4141. Moscucci M, Fox KA, Cannon CP, Klein W, Lopez-Sendon J, Montalescot G, White K, Goldberg RJ: Predictors of major bleeding in acute coronary syndromes: the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE). Eur Heart J. 2003;24:1815-23. ]. In practical terms, these specificities do not have an overall impact and no specific measures for female patients are advocated after PCI.

ELDERLY PATIENTS

In elderly patients, the question often arises of the bleeding risk incurred by the association of aspirin and thienopyridines, as well as the further question of the efficacy of statin therapy in this population. Although increasing age is a significant predictor of bleeding under dual antiplatelet therapy, the addition of clopidogrel to aspirin alone in the CURE study showed the same absolute beneficial effect in younger patients (<65 years) as in older patients [4242. Yusuf S, Zhao F, Mehta SR, Chrolavicius S, Tognoni G, Fox KK: Effects of clopidogrel in addition to aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes without ST-segment elevation. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:494-502. ]. In the TRITON study, prasugrel was associated with an excess of bleeding events in patients aged >75 years, and this increase cancelled out the benefit achieved in terms of thrombotic risk [4343. Wiviott SD, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, Montalescot G, Ruzyllo W, Gottlieb S, Neumann FJ, Ardissino D, De Servi S, Murphy SA, Riesmeyer J, Weerakkody G, Gibson CM, Antman EM: Prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2001-15. ]. Finally, in the PLATO study, in patients planned to undergo invasive strategy, the benefit of ticagrelor was identical in patients above and below 65 years of age [4444. Cannon CP, Harrington RA, James S, Ardissino D, Becker RC, Emanuelsson H, Husted S, Katus H, Keltai M, Khurmi NS, Kontny F, Lewis BS, Steg PG, Storey RF, Wojdyla D, Wallentin L: Comparison of ticagrelor with clopidogrel in patients with a planned invasive strategy for acute coronary syndromes (PLATO): a randomised double-blind study. Lancet. 2010;375:283-93. ]. However, beyond 75 years of age, the reduction in thrombotic risk was lower, albeit without excess bleeding, thus rendering the net clincial benefit of ticagrelor non-significant. These comparative data from different P2Y12 receptor inhibitors were all obtained in patients with ACS only; thus, clodpigrel and ticagrelor can be used in patients older than 75 years.

The benefit of statin therapy in elderly patietns (70 to 82 years) for primary and secondary prevention was demonstrated with a reduction in mortality and in the rate of MI [4545. Shepherd J, Blauw GJ, Murphy MB, Bollen EL, Buckley BM, Cobbe SM, Ford I, Gaw A, Hyland M, Jukema JW, Kamper AM, Macfarlane PW, Meinders AE, Norrie J, Packard CJ, Perry IJ, Stott DJ, Sweeney BJ, Twomey C, Westendorp RG: Pravastatin in elderly individuals at risk of vascular disease (PROSPER): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360:1623-30. ]. Similarly, the Cooperative Cardiovascular Project demonstrated the efficacy of beta-blockers after PCI in patients >65 years, with a 14% reduction in mortality at 1 year [4646. Chen J, Radford MJ, Wang Y, Marciniak TA, Krumholz HM: Are beta-blockers effective in elderly patients who undergo coronary revascularization after acute myocardial infarction? Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:947-52. ].

DIABETIC PATIENTS

In the days following a PCI procedure, particularly attention should be paid to the detection of nephrotoxicity in patients with diabetes [2828. Windecker S, Kolh P, Alfonso F, Collet JP, Cremer J, Falk V, Filippatos G, Hamm C, Head SJ, Juni P, Kappetein AP, Kastrati A, Knuuti J, Landmesser U, Laufer G, Neumann FJ, Richter DJ, Schauerte P, Sousa Uva M, Stefanini GG, Taggart DP, Torracca L, Valgimigli M, Wijns W, Witkowski A: 2014 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization: The Task Force on Myocardial Revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS)Developed with the special contribution of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI). Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2541-619. ]. The risk of contrast-induced nephrotoxicity is increased in diabetic patients and in those with renal insufficienty, and the increase in risk is proportional to the quantity of contrast medium used [4747. Mehran R, Aymong ED, Nikolsky E, Lasic Z, Iakovou I, Fahy M, Mintz GS, Lansky AJ, Moses JW, Stone GW, Leon MB, Dangas G: A simple risk score for prediction of contrast-induced nephropathy after percutaneous coronary intervention: development and initial validation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:1393-9. ]. Myocardial ischemia can often be asymptomatic in diabetic patients, justifying the use of functional evaluations to detect restenosis, particularly since this phenomenon is more frequent in diabetic patients, regardless of the type of stent used. No specific additional treatment after PCI is required for diabetic patients, and secondary prevention and antithrombotic therapies also remain unchanged. The sole difference is a situation of PCI in the context of ACS, where treatment by prasugrel or ticagrelor should be preferred over clopidogrel in diabetic patients.

PATIENTS WITH RENAL INSUFFICIENCY

Patients with renal insufficiency are characterised by two distinct features:

- The risk of contrast-induced nephrotoxicity. The mechanism of this nephrotoxicity is tubular necrosis, which generally regresses within a few weeks, and evolution towards end-stage renal disease is rare. There is no consensus on the threshold beyond which patients should not received contrast medium. In one report, 35% of radiologists used a threshold creatinine clearance value of 1.5 mg/dL, 27% used a threshold of 1.7 mg/dL, while a further 31% advocated a threshold of 2.0 mg/dL to determine patients in whom contrast medium should be contra-indicated [4848. Elicker BM, Cypel YS, Weinreb JC: IV contrast administration for CT: a survey of practices for the screening and prevention of contrast nephropathy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186:1651-8. ]. The increase in creatinine is at its maximum 48 hours after the injection of iodinated contrast agents. The presence of pre-existing renal dysfunction favours nephrotoxocity, and thus, in addition to preventive measures before, during and immediately after PCI, it is also necessary to verify renal function in patients with renal insufficiency.

- Tolerance to secondary prevention treatments. Secondary prevention measures should be the same in patients with renal insufficiency as in other patient subgroups. Only ACEI or ARA2 may pose a particular problem. The presence of renal dysfunction can represent an additional justification for the prescription of ACEI or ARA2, whose renal protective role has previously been demonstrated. Administration of ACEI should be closely monitored for biological tolerance, bearing in mind that a moderate increase (up to 20%) in creatinine after initiation of ACEI therapy can be observed and is related to the correction of glomerular hypertension.

PATIENTS TREATED WITH ORAL ANTICOAGULANTS

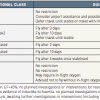

The presence of a mechanical prosthesis, thrombo-embolic disease or atrial fibrillation justifies prescription of long-term anticoagulant therapy, and when associated with antiplatelet agents, this can increase the risk of bleeding complications, either spontaneous bleeding or procedure-related. For this reason, bare metal stents should be preferred in these patient groups, in order to reduce to one month the duration of the triple association of antiplatelet, anticoagulant and antithrombotic agents, particularly outside the context of diabetes, long lesions or small-calibre vessels.

The duration of the triple association is one month for conventional stents, 3 to 6 months for drug-eluting stents (3 months for sirolimus- and 6 months for paclitaxel-eluting stents). During this time, strict monitoring of antivitamin K treatment is necessary, targeting an international normalized ratio (INR) value between 2 and 2.5. The dose of aspirin should be between 75 and 100mg, and the use of gastro-intestinal bleeding proxphylaxis is recommended (proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), H2 antagonists, or antacids). After this period, a combination of antivitamin K and clopidogrel is the only recommended treatment, and in stable patients at high risk of bleeding (as estimated by the HAS-BLED score), antivitamin K therapy alone is recommended, without any associated antiplatelet agent. Despite the lack of strong evidence in this patient subset, a position paper from the ESC has proposed to adapt the duration and type of antithrombotic treatment to the patient characteristics (namely, bleeding risk), and to the PCI setting (stable or ACS). In this document, the anti-thrombotic strategy can be chosen irrespective of the type of stent implanted (BMS or DES) and irrespective of the type of anticoagulant (Vitamin K antagonist or direct oral anticoagulant) [4949. Lip GY, Windecker S, Huber K, Kirchhof P, Marin F, Ten Berg JM, Haeusler KG, Boriani G, Capodanno D, Gilard M, Zeymer U, Lane D, Storey RF, Bueno H, Collet JP, Fauchier L, Halvorsen S, Lettino M, Morais J, Mueller C, Potpara TS, Rasmussen LH, Rubboli A, Tamargo J, Valgimigli M, Zamorano JL: Management of antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome and/or undergoing percutaneous coronary or valve interventions: a joint consensus document of the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Thrombosis, European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA), European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI) and European Association of Acute Cardiac Care (ACCA) endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) and Asia-Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS). Eur Heart J. 2014;35:3155-79. ] ( Figure 4 )

Lastly, beta blockers are preferentially indicated for the control of heart rate in patients with CAD and atrial fibrillation [2828. Windecker S, Kolh P, Alfonso F, Collet JP, Cremer J, Falk V, Filippatos G, Hamm C, Head SJ, Juni P, Kappetein AP, Kastrati A, Knuuti J, Landmesser U, Laufer G, Neumann FJ, Richter DJ, Schauerte P, Sousa Uva M, Stefanini GG, Taggart DP, Torracca L, Valgimigli M, Wijns W, Witkowski A: 2014 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization: The Task Force on Myocardial Revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS)Developed with the special contribution of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI). Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2541-619. ].

Specfic conditions for secondary prevention after PCI: lesions subsets

Situations specific to a site or technique of angioplasty can be defined such as main stem lesions, bifurcation lesions, chronic occlusion, restenosis or incomplete revascularisation, balloon angioplasty or rotational atherectomy. Specific strategies for secondary prevention and follow-up can be envisaged in these populations.

LEFT MAIN LESIONS (OR EQUIVALENT)

Suboptimal response to clopidogrel therapy, particularly in carriers of a loss-of-function allele for CYP2C19, is associated with a higher rate of cardiovascular events [. ]. After PCI, irrespective of the site involved, there is an increased risk of stent thrombosis in clopidogrel hyporesponders [2929. Buonamici P, Marcucci R, Migliorini A, Gensini GF, Santini A, Paniccia R, Moschi G, Gori AM, Abbate R, Antoniucci D: Impact of platelet reactivity after clopidogrel administration on drug-eluting stent thrombosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:2312-7. ], underlining the interest of monitoring for clopidogrel response (for example using functional or genetic testing), particularly in PCI of main vessels, like the main stem. Currently, although the use of high doses of clopidogrel in patients with suboptimal response has been shown to be beneficial [5151. Bonello L, Camoin-Jau L, Armero S, Com O, Arques S, Burignat-Bonello C, Giacomoni MP, Bonello R, Collet F, Rossi P, Barragan P, Dignat-George F, Paganelli F: Tailored clopidogrel loading dose according to platelet reactivity monitoring to prevent acute and subacute stent thrombosis. Am J Cardiol. 2009;103:5-10. ], there is no scientific evidence to support a benefit of such monitoring, and current guidelines do not recommendation systematic monitoring.

Multiple stent implantation, small vessels, bifurcation are usually considered as situations at high risk of thrombosis. In these cases, and when the patient is not considered to be at high risk of bleeding, a longer duration of DAPT must be considered [66. Bonaca MP, Bhatt DL, Cohen M, Steg PG, Storey RF, Jensen EC, Magnani G, Bansilal S, Fish MP, Im K, Bengtsson O, Ophuis TO, Budaj A, Theroux P, Ruda M, Hamm C, Goto S, Spinar J, Nicolau JC, Kiss RG, Murphy SA, Wiviott SD, Held P, Braunwald E, Sabatine MS: Long-Term Use of Ticagrelor in Patients with Prior Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med. 2015. , 2626. Mauri L, Kereiakes DJ, Yeh RW, Driscoll-Shempp P, Cutlip DE, Steg PG, Normand SL, Braunwald E, Wiviott SD, Cohen DJ, Holmes DR, Jr., Krucoff MW, Hermiller J, Dauerman HL, Simon DI, Kandzari DE, Garratt KN, Lee DP, Pow TK, Ver Lee P, Rinaldi MJ, Massaro JM: Twelve or 30 months of dual antiplatelet therapy after drug-eluting stents. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2155-66. ].

PCI TECHNIQUE

The risk of restenosis, depending on the angioplasty technique used, can impact the follow-up strategy. Indeed, after balloon angioplasty alone, the expected restenosis rate is higher than after angioplasty with bare-metal or active stent implantation. Similarly, the use of atherectomy has reportedly been associated with an increased risk of restenosis [5252. Dill T, Dietz U, Hamm CW, Kuchler R, Rupprecht HJ, Haude M, Cyran J, Ozbek C, Kuck KH, Berger J, Erbel R: A randomized comparison of balloon angioplasty versus rotational atherectomy in complex coronary lesions (COBRA study). Eur Heart J. 2000;21:1759-66. ]. Certain types of lesions more generally expose the patient to a higher risk of restenosis, such as bifurcation lesions, chronic occlusions, lesions on saphenous veing grafts, and in-stent restenosis. In these situations, tailored follow-up with easier access to control angiography, can be envisaged.

Conclusions

The interventional cardiologist’s job does not end at the door of the catheterisation laboratory, but rather covers the whole spectrum of treatment plus information to the patient and treating physicians regarding the modalities of prevention, specific treatment and follow-up.

Lifestyle measures and secondary prevention therapy are not specific to patients undergoing PCI, but the modalities of antiplatelet therapy and detection of early and late post-PCI complications do depend on the type of procedure performed, as well as on the patient’s characteristics. Only the interventional cardiologist is suitably qualified to dispense appropriate advice regarding the adaptation of treatment and follow-up according to the type of procedure, the type of stent, the lesion(s) treated, the complete or incomplete nature of the revascularisation, the bleeding risk, and the patient’s age, sex and renal function.