Background

Calcific aortic stenosis (AS) is the most frequent valvular heart disease in the Western world. Its prevalence increases with age. Community data documents the prevalence of moderate or severe AS as 0.6%, 1.4% to 4.6% in patients aged 55 to 64, 65 to 74, and ≥75 years of age, respectively [11. Nkomo VT, Gardin JM, Skelton TN, Gottdiener JS, Scott CG, Enriquez-Sarano M. Burden of valvular heart diseases: a population-based study. Lancet. 2006 Sep 16;368(9540):1005-11. ]. Once moderate AS is present progression is somewhat predictable with an average reduction in aortic valve area of 0.1cm2/year [22. Rosenhek R, Binder T, Porenta G, Lang I, Christ G, Schemper M, Maurer G, Baumgartner H. Predictors of outcome in severe, asymptomatic aortic stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:611-7. ], and simultaneous increase in the transvalvular gradient, eventually resulting in typical symptoms of angina, syncope and heart failure. Once these symptoms are present the average survival is 2 to 3 years [33. Pellikka PA, Sarano ME, Nishimura RA, Malouf JF, Bailey KR, Scott CG, Barnes ME, Tajik AJ. Outcome of 622 adults with asymptomatic, hemodynamically significant aortic stenosis during prolonged follow-up. Circulation. 2005;111:3290-5. , 44. Ross J, Jr., Braunwald E. Aortic stenosis. Circulation. 1968;38(1 Suppl):61-7. , 55. Turina J, Hess O, Sepulcri F, Krayenbuehl HP. Spontaneous course of aortic valve disease. Eur Heart J. 1987:471-83. ].

Before the era of TAVI, only surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) was appropriate and possible to offer survival and symptomatic benefit. However, about one-third of the patients could not be operated either because of their advanced age or their co-morbidities [66. Iung B, Baron G, Butchart EG, Delahaye F, Gohlke-Barwolf C, Levang OW, Tornos P, Vanoverschelde JL, Vermeer F, Boersma E, Ravaud P, Vahanian A. A prospective survey of patients with valvular heart disease in Europe: The Euro Heart Survey on Valvular Heart Disease. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:1231-43. ].

Percutaneous balloon aortic valvuloplasty (BAV) for calcific aortic stenosis was first reported by Cribier in 1986 [77. Cribier A, Savin T, Saoudi N, Rocha P, Berland J, Letac B. Percutaneous transluminal valvuloplasty of acquired aortic stenosis in elderly patients: an alternative to valve replacement? Lancet. 1986;63-7.

First FIM BAV report]. After a major initial enthusiasm of the cardiology community, it became apparent that initial haemodynamic and symptomatic improvement was transient and related to a very high rate of restenosis. Furthermore, survival was not improved and similar to that of untreated AS.

Since 2017, European Society of Cardiology and American College of Cardiology/ American Heart Association have revisited the indication for aortic valve intervention given the results of new randomized studies in particular in intermediate-risk patients. In summary, SAVR is indicated for low-risk patients with severe AS and symptoms, reduced LV function, and in some asymptomatic patients. TAVI has received growing attention and is now not limited to inoperable and high-risk patients and is an alternative to surgery in intermediate-risk patients when a transfemoral approach is feasible [88. Baumgartner H, Falk V, Bax JJ, De Bonis M, Hamm C, Holm PJ, Iung B, Lancellotti P, Lansac E, Rodriguez Muñoz D, Rosenhek R, Sjögren J, Tornos Mas P, Vahanian A, Walther T, Wendler O, Windecker S, Zamorano JL; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2017 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J 2017;38:2739-2791. , 99. Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Erwin JP 3rd, Fleisher LA, Jneid H, Mack MJ, McLeod CJ, O’Gara PT, Rigolin VH, Sundt TM 3rd, Thompson A. 2017 AHA/ACC Focused Update of the 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:252-289. ]. In contrast, the place of BAV is very limited (class IIb, C) and may be considered: 1) as a bridge to SAVR or TAVI in haemodynamically unstable patients; 2) in patients with symptomatic severe aortic stenosis who require urgent major non-cardiac surgery; 3) as a diagnostic means in patients with severe aortic stenosis or other potential causes for symptoms (i.e. lung disease) and in patients with severe myocardial dysfunction, pre-renal insufficiency or other organ dysfunction that may be reversible with BAV when performed in centres that can escalate to TAVI [88. Baumgartner H, Falk V, Bax JJ, De Bonis M, Hamm C, Holm PJ, Iung B, Lancellotti P, Lansac E, Rodriguez Muñoz D, Rosenhek R, Sjögren J, Tornos Mas P, Vahanian A, Walther T, Wendler O, Windecker S, Zamorano JL; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2017 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J 2017;38:2739-2791. , 99. Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Erwin JP 3rd, Fleisher LA, Jneid H, Mack MJ, McLeod CJ, O’Gara PT, Rigolin VH, Sundt TM 3rd, Thompson A. 2017 AHA/ACC Focused Update of the 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:252-289. ].

Aortic stenosis European guidelines

- Aortic stenosis is the most frequent valvular disease in the Western world. Its prevalence increases with age

- Current guidelines recommend surgical aortic valve replacement for low-risk patients with severe AS and symptoms, reduced LV function or concomitant heart surgery

- Current guidelines recommend TAVI in patients with severe AS and symptoms, if inoperable or at high-risk for surgery. TAVI is also an alternative for surgery in intermediate-risk patients when a transfemoral approach is feasible.

THE PROCEDURE

The common femoral artery is punctured superior to its bifurcation into the superficial and deep femoral arteries, and below the inguinal ligament. The femoral acetabulum serves as a useful fluoroscopic landmark. Pre-closure of the puncture site can be performed, using a 10 Fr Prostar or one or two 6 Fr ProGlide suture devices (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL, USA). Closure with Angio-Seal (St. Jude Medical, St. Paul, MN, USA) 8 Fr is another alternative. An 8 Fr to 14 Fr sheath is placed depending on the size and type of valvuloplasty balloon selected. Heparin is typically administered (70 IU/Kg) and frequently reversed by protamine at the end of the procedure.

A diagnostic coronary catheter is introduced into the aortic root over a standard J wire. An Amplatz left 1 for a narrow or vertical root and an Amplatz left 2 catheter for a larger or more horizontal root are typically favoured, although a Judkins right, multipurpose or pigtail catheter can be used. A straight tipped 0.035” wire is carefully manipulated in a probing manner making gentle passes across the central orifice of the stenotic valve [1010. Cribier A, Eltchaninoff H. Tips and tricks for crossing the aortic valve with a guidewire (retrograde approach). In: Serruys PW PN, Cribier A, Webb J, Laborde JC, de Jaeger P, editor. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation Tips and tricks to avoid failure. New York: Informa Healthcare; 2010. p.

155-70]. After gaining access to the left ventricle the wire and catheter are exchanged for an 0.035” exchange 260 cm length stiff wire (e.g., Amplatz extra stiff 3 cm soft tip J; Cook Medical Inc., Bloomington, IN, USA DK) which offers optimal support but has a softer tip which must be manually-shaped by the operator to sit atraumatically within the ventricle.

In contrast to the common transarterial retrograde technique just described, a transvenous approach can be used in particular when a femoral approach is impossible [1212. Sakata Y, Syed Z, Salinger MH, Feldman T. Percutaneous balloon aortic valvuloplasty: antegrade transseptal vs. conventional retrograde transarterial approach. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2005;64:314-21. ]. This involves femoral venous puncture followed by transseptal access to the left atrium, through the mitral valve and then antegrade across the aortic valve. Potential advantages of this approach are the safety of large sheath access via the femoral vein, ease of crossing the stenotic aortic valve from the ventricle and balloon stability during inflation. This approach, however, is less commonly used due to complexity and the need for transseptal access and is usually restricted to patients with no suitable femoral arterial access.

Techniques of balloon aortic valvuloplasty

- BAV has become simple and quite safe.

- It is performed under local anaesthesia using the common femoral retrograde approach using standard catheterisation technique

- Balloon inflation is performed under rapid ventricular pacing so as to stabilise the balloon across the aortic valve

BALLOON STABILISATION

Balloon catheter stability during valvuloplasty is crucial, because during inflation the balloon tends to be ejected into the aorta. A balloon length of 4 to 5 cm is generally preferred as 3 cm balloons are difficult to stabilise and 6 cm balloons require prolonged inflation, Self-seating hourglass shaped balloons can also improve stability markedly ( Figure 2).

Rapid ventricular burst pacing is often used to reduce systemic arterial blood pressure, transvalvular flow and cardiac motion during BAV [1313. Webb JG, Pasupati S, Achtem L, Thompson CR. Rapid pacing to facilitate transcatheter prosthetic heart valve implantation. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2006;68:199-204.

Report on use of rapid pacing]. Typically a transvenous right ventricular pacing lead is utilised with burst pacing at rates of 160 to 220 per minute ( Figure 3 - Panel A). Reliable 1:1 ventricular capture must be obtained ( Figure 3 - Panel B). There is potential for ischaemic left ventricular dysfunction with hypotension and ventricular arrhythmias. Burst pacing should be of short duration and defibrillation readily available. Patients must be warned beforehand that they may feel temporarily dizzy and presyncopal during balloon inflation. If the patient is hypotensive before or after BAV, 100 to 200 mcg of phenylephrine, repeated as necessary, may rapidly and very safely bring the pressure up without causing tachycardia or ventricular arrhythmia.

Of note, “direct left ventricular rapid pacing” is also possible to simplify BAV and

TAVI procedure. This technique consists in a left ventricular pacing through the 0.35 inch back up guidewire inserted into the left ventricle. The cathode of an external pacemaker is placed on the external end of the 0.35’ wire using an alligator clamp. The anode is placed (also using an alligator clamp) on a small needle piercing the subcutaneous tissue at the site of the anesthetized groin [1414. Faurie B, Abdellaoui M, Wautot F, Staat P, Champagnac D, Wintzer-Wehekind J, Vanzetto G, Bertrand B, Monségu J. Rapid pacing using the left ventricular guidewire: Reviving an old technique to simplify BAV and TAVI procedures. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2016 Nov 15;88(6):988-993. ].

EVIDENCE FOR EFFICACY

BAV has never been subjected to a large scale randomised trial.

Informed practice is dependent on large multicentre registries from the late 1980’s, such as the Mansfield Scientific Balloon Aortic Valvuloplasty Registry [2828. Bashore TM, Davidson CJ. Follow-up recatheterization after balloon aortic valvuloplasty. Mansfield Scientific Aortic Valvuloplasty Registry Investigators. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;17:1188-95. , 2929. Ferguson JJ, Garza RA. Efficacy of multiple balloon aortic valvuloplasty procedures. The Mansfield Scientific Aortic Valvuloplasty Registry Investigators. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;17:1430-5. , 3030. Isner JM. Acute catastrophic complications of balloon aortic valvuloplasty. The Mansfield Scientific Aortic Valvuloplasty Registry Investigators. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;17:1436-44. , 3131. McKay RG. The Mansfield Scientific Aortic Valvuloplasty Registry: overview of acute hemodynamic results and procedural complications. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;17:485-91. , 3232. Nishimura RA, Holmes DR, Jr., Michela MA. Follow-up of patients with low output, low gradient hemodynamics after percutaneous balloon aortic valvuloplasty: the Mansfield Scientific Aortic Valvuloplasty Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;17:828-33. , 3333. O’Neill WW. Predictors of long-term survival after percutaneous aortic valvuloplasty: report of the Mansfield Scientific Balloon Aortic Valvuloplasty Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;17:193-8. , 3434. O’Neill WW. Seminar on Balloon Aortic Valvuloplasty - I: Introduction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;17:187-8. , 3535. Reeder GS, Nishimura RA, Holmes DR, Jr. Patient age and results of balloon aortic valvuloplasty: the Mansfield Scientific Registry experience. The Mansfield Scientific Aortic Valvuloplasty Registry Investigators. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991 Mar;909-13. ] and the NHLBI Balloon Valvuloplasty Registry [3636. Otto CM, Mickel MC, Kennedy JW, Alderman EL, Bashore TM, Block PC, Brinker JA, Diver D, Ferguson J, Holmes DR Jr. Three-year outcome after balloon aortic valvuloplasty. Insights into prognosis of valvular aortic stenosis. Circulation. 1994;89:642-50. , 3737. Participants. NBVR. Percutaneous balloon aortic valvuloplasty. Acute and 30-day follow-up results in 674 patients from the NHLBI Balloon Valvuloplasty Registry. Circulation. 1991;84:2383-97. ] and on single centre registries. [3838. Eltchaninoff H, Cribier A, Tron C, Anselme F, Koning R, Soyer R, Letac B. Balloon aortic valvuloplasty in elderly patients at high risk for surgery, or inoperable. Immediate and mid-term results. Eur Heart J. 1995;16:1079-84.

Single large registry on BAV in pioneering experienced center, 3939. Koning R, Cribier A, Asselin C, Mouton-Schleifer D, Derumeaux G, Letac B. Repeat balloon aortic valvuloplasty. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1992;26:249-54. , 4040. Letac B, Cribier A, Koning R, Bellefleur JP. Results of percutaneous transluminal valvuloplasty in 218 adults with valvular aortic stenosis. Am J Cardiol 1988;598-605. , 4141. Letac B, Cribier A, Koning R, Lefebvre E. Aortic stenosis in elderly patients aged 80 or older. Treatment by percutaneous balloon valvuloplasty in a series of 92 cases. Circulation. 1989;80:1514-20. , 4242. Berland J, Cribier A, Savin T, Lefebvre E, Koning R, Letac B. Percutaneous balloon valvuloplasty in patients with severe aortic stenosis and low ejection fraction. Immediate results and 1-year follow-up. Circulation. 1989;79:1189-96.

BAV in a specific subset of patients with low ejection fraction, 4343. Davidson CJ, Harrison JK, Pieper KS, Harding M, Hermiller JB, Kisslo K, Pierce C, Bashore TM. Determinants of one-year outcome from balloon aortic valvuloplasty. Am J Cardiol 1991;68:75-80. , 4444. Lieberman EB, Bashore TM, Hermiller JB, Wilson JS, Pieper KS, Keeler GP, Pierce CH, Kisslo KB, Harrison JK, Davidson CJ. Balloon aortic valvuloplasty in adults: failure of procedure to improve long-term survival. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;26:1522-8. , 4545. Lieberman EB, Wilson JS, Harrison JK, Pieper KS, Kisslo KB, Lowe J, Douglas J Jr, Van Trigt P, Glower DD, Davidson CJ. Aortic valve replacement in adults after balloon aortic valvuloplasty. Circulation. 1994;90(5 Pt 2):II205-8. , 4646. Boone RH WJ. Nonsurgical aortic valve therapy: Balloon valvuloplasty and transcatheter aortic valve replacement. In: Yusuf S CJ, Camm J, Fallen E, Gersh B, editor. Evidence Based Cardiology. 3rd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; 2008.

Review of BAV].

Boone et al. summarised findings from 50 publications documenting results from over 2,400, primarily elderly non-operative or high-risk operative, patients [4646. Boone RH WJ. Nonsurgical aortic valve therapy: Balloon valvuloplasty and transcatheter aortic valve replacement. In: Yusuf S CJ, Camm J, Fallen E, Gersh B, editor. Evidence Based Cardiology. 3rd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; 2008.

Review of BAV]. All reports were case series (Level of Evidence C). Excluded were reports of BAV in young patients with congenital AS where BAV remains a Class I therapeutic option [4646. Boone RH WJ. Nonsurgical aortic valve therapy: Balloon valvuloplasty and transcatheter aortic valve replacement. In: Yusuf S CJ, Camm J, Fallen E, Gersh B, editor. Evidence Based Cardiology. 3rd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; 2008.

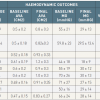

Review of BAV]. Changes in aortic valve area and mean transaortic gradient are summarised in table 1. Generally valve area increased to between 0.8 and 1cm2 ( table 1). It appeared that BAV was successful in reducing the transaortic gradient to < 25 mm a modest degree in most, but not all, patients with critical calcific AS.

Published series consistently report significant improvement in symptoms in 50% to 75% of survivors. Advanced age, poor left ventricular function and poor functional class appear to be the main pre-procedural predictors of poor outcome [3636. Otto CM, Mickel MC, Kennedy JW, Alderman EL, Bashore TM, Block PC, Brinker JA, Diver D, Ferguson J, Holmes DR Jr. Three-year outcome after balloon aortic valvuloplasty. Insights into prognosis of valvular aortic stenosis. Circulation. 1994;89:642-50. ]. In one analysis less than half of those with a left ventricular ejection fraction <45% had symptomatic improvement [4848. Davidson CJ, Harrison JK, Leithe ME, Kisslo KB, Bashore TM. Failure of balloon aortic valvuloplasty to result in sustained clinical improvement in patients with depressed left ventricular function. Am J Cardiol. 1990;65:72-7. ]. Although most patients experience some haemodynamic and symptomatic improvement these changes were generally small. Moreover the benefit was not durable. The reported rate of valvular restenosis (defined as ≥50% loss in the valve area achieved following BAV) varies between 25 and 47% at 6 months [4949. Agarwal A, Kini AS, Attanti S, Lee PC, Ashtiani R, Steinheimer AM, Moreno PR, Sharma SK. Results of repeat balloon valvuloplasty for treatment of aortic stenosis in patients aged 59 to 104 years. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:43-7.

Usefulness of repeat BAV to improve survival, 5050. Bernard Y, Etievent J, Mourand JL, Anguenot T, Schiele F, Guseibat M, Bassand JP. Long-term results of percutaneous aortic valvuloplasty compared with aortic valve replacement in patients more than 75 years old. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;20:796-801. , 5151. Block PC, Palacios IF. Clinical and hemodynamic follow-up after percutaneous aortic valvuloplasty in the elderly. Am J Cardiol. 1988;62(10 Pt 1):760-3. , 5252. Safian RD, Berman AD, Diver DJ, McKay LL, Come PC, Riley MF, Warren SE, Cunningham MJ, Wyman RM, Weinstein JS, et al. Balloon aortic valvuloplasty in 170 consecutive patients. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:125-30. ] and up to 80% at 15 months [5353. Letac B, Cribier A, Eltchaninoff H, Koning R, Derumeaux G. Evaluation of restenosis after balloon dilatation in adult aortic stenosis by repeat catheterization. American Heart Journal. 1991;122(1 Pt 1):55-60.

Report on restenosis after BAV].

Survival ranged from 75-38% (average 65%) and 28-60% (average 35%) at one year and two years respectively. These survival statistics are similar to that of untreated AS in elderly patients [55. Turina J, Hess O, Sepulcri F, Krayenbuehl HP. Spontaneous course of aortic valve disease. Eur Heart J. 1987:471-83. , 5454. Pai RG, Kapoor N, Bansal RC, Varadarajan P. Malignant natural history of asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis: benefit of aortic valve replacement. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;82:2116-22. ]. Furthermore, the impact of BAV in patients not undergoing aortic valve replacement in the PARTNER trial (cohort 1B) has been recently reported. Survival at 3 months was greater in the BAV group compared with the no BAV group (88.2% vs. 73.0%) whereas survival was similar at 6-month follow-up (74.5% vs. 73.1%). There was improvement in quality of life parameters when paired comparisons were made between baseline and 30 days and 6 months between the BAV and no BAV groups, but this effect was lost at 12-month follow-up [5555. Kapadia S, Stewart WJ, Anderson WN, Baba- liaros V, Feldman T, Cohen DJ, Douglas PS, Makkar RR, Svensson LG, Webb JG, Wong SC, Brown D, Miller C, Moses JW, Smith CR, Leon MB, Tuzcu M. Outcomes of inoperable symptomatic aortic stenosis patients not undergoing aortic valve replace- ment: insight into the impact of balloon aortic valvuloplasty from the PARTNER trial (Place-ment of AoRtic TraNscathetER Valve trial).JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2015;8:324–33. ].

It appears, therefore, that BAV alone does not alter the natural history of AS for the majority of patients. As a consequence current AHA/ACC guidelines give a class III recommendation to the concept of BAV as an alternative to surgical valve replacement ( Table 2) [4646. Boone RH WJ. Nonsurgical aortic valve therapy: Balloon valvuloplasty and transcatheter aortic valve replacement. In: Yusuf S CJ, Camm J, Fallen E, Gersh B, editor. Evidence Based Cardiology. 3rd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; 2008.

Review of BAV].

BAV results

- BAV is successful in reducing the transvalvular gradient, improving symptoms and left ventricular ejection fraction

- The restenosis rate is high, close to 80% at one year and BAV does not improve survival when performed as a stand-alone procedure

ESTIMATION OF ANNULUS SIZE

An estimate of aortic annular diameter is desirable to select an appropriate sized valvuloplasty balloon. As a very rough rule of thumb, small patients may be appropriately treated with an 18 to 20 mm balloon, medium patients with a 22 to 24 mm balloon and large patients with a 25 to 28 mm balloon. An undersized balloon will have little effect, while an oversized balloon runs the risk of annular injury. Echocardiographic assessment of annular size is more reliable. Aortography may be helpful, however it should be remembered that the left ventricular outflow portion of the aortic annulus is not visualised during aortography ( Figure 4).

The sizing of the aortic annulus diameter is important prior to TAVI in order to facilitate the selection of an appropriate implant. If the diameter of an inflated valvuloplasty balloon is known then this may assist in this evaluation. Balloon diameter can be determined according to the labelled balloon size or can be estimated with calibration software. Correlation with root size can be facilitated by a simultaneous aortic root contrast injection during balloon inflation. In addition an assessment can be made of the potential for coronary obstruction at the time of TAVI ( Figure 4).

’Push-back’’ pressure as measured from a manometer attached to the balloon lumen or inflation device has been correlated with aortic annular diameter. Pressure can be seen to rise abruptly as the balloon comes into contact with the annulus during inflation. This has been advocated as a sizing technique during TAVI [5656. Babaliaros VC, Junagadhwalla Z, Lerakis S, Thourani V, Liff D, Chen E, Vassiliades T, Chappell C, Gross N, Patel A, Howell S, Green JT, Veledar E, Guyton R, Block PC. Use of balloon aortic valvuloplasty to size the aortic annulus before implantation of a balloon-expandable transcatheter heart valve. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;3:114-8. ].

COMPLICATIONS

The reported incidence of complications varied widely in the early registries ( table 1), with the overall complication rate ranging from 9% to 25%. The latest results of Rouen large experience on more than 300 patients suggest that risks in contemporary practice include renal failure, stroke (1.9%), vascular complications (1.9%), annular rupture (0.3%) and, exceptionally, pericardial tamponade [5959. Eltchaninoff H, Durand E, Borz B, Furuta A, Bejar K, Canville A, Farhat A, Fraccaro C, Godin M, Tron C, Sakhuja R, Cribier A. Balloon aortic valvuloplasty in the era of transcatheter aortic valve replacement: acute and long-term outcomes. Am Heart J. 2014;167:235-40. ]. Several groups confirm that procedural complications have been reduced considerably in comparison to early experience [3131. McKay RG. The Mansfield Scientific Aortic Valvuloplasty Registry: overview of acute hemodynamic results and procedural complications. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;17:485-91. , 3737. Participants. NBVR. Percutaneous balloon aortic valvuloplasty. Acute and 30-day follow-up results in 674 patients from the NHLBI Balloon Valvuloplasty Registry. Circulation. 1991;84:2383-97. , 4040. Letac B, Cribier A, Koning R, Bellefleur JP. Results of percutaneous transluminal valvuloplasty in 218 adults with valvular aortic stenosis. Am J Cardiol 1988;598-605. , 4949. Agarwal A, Kini AS, Attanti S, Lee PC, Ashtiani R, Steinheimer AM, Moreno PR, Sharma SK. Results of repeat balloon valvuloplasty for treatment of aortic stenosis in patients aged 59 to 104 years. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:43-7.

Usefulness of repeat BAV to improve survival, 5252. Safian RD, Berman AD, Diver DJ, McKay LL, Come PC, Riley MF, Warren SE, Cunningham MJ, Wyman RM, Weinstein JS, et al. Balloon aortic valvuloplasty in 170 consecutive patients. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:125-30. , 5757. Block PC. The experience curve for percutaneous aortic valvuloplasty. Report from the Mansfield Scientific Aortic Valvulplasty Registry. Circulation. 1988;78(Suppl II):II-531. , 5858. Klein A, Lee K, Gera A, Ports TA, Michaels AD. Long-term mortality, cause of death, and temporal trends in complications after percutaneous aortic balloon valvuloplasty for calcific aortic stenosis. J Interv Cardiol. 2006;19:269-75. , 5959. Eltchaninoff H, Durand E, Borz B, Furuta A, Bejar K, Canville A, Farhat A, Fraccaro C, Godin M, Tron C, Sakhuja R, Cribier A. Balloon aortic valvuloplasty in the era of transcatheter aortic valve replacement: acute and long-term outcomes. Am Heart J. 2014;167:235-40. ]. It seems that with increased procedural experience, changes in technique and refinements in equipment the procedure is becoming safer and more routine, albeit not entirely without complications.

BAV complications

- With improved technique and operator skills, complications are rare

- Massive aortic regurgitation occurs in less than < 2%

RESTENOSIS AFTER BAV

BAV improves leaflet mobility by fracturing calcified nodules and creating cleavage planes within collagenous stroma [6060. Safian RD, Mandell VS, Thurer RE, Hutchins GM, Schnitt SJ, Grossman W, McKay RG. Postmortem and intraoperative balloon valvuloplasty of calcific aortic stenosis in elderly patients: mechanisms of successful dilation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1987;655-60. , 6161. McKay RG, Safian RD, Lock JE, Mandell VS, Thurer RL, Schnitt SJ, Grossman W. Balloon dilatation of calcific aortic stenosis in elderly patients: postmortem, intraoperative, and percutaneous valvuloplasty studies. Circulation. 1986;74:119-25. ]. Unfortunately restenosis is a constant finding following BAV. The process of restenosis involves granulation tissue, fibrosis and active osteoblast mediated calcification within the valve leaflets [6262. Feldman T, Glagov S, Carroll JD. Restenosis following successful balloon valvuloplasty: bone formation in aortic valve leaflets. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1993;29:1-7. ].

Given the early benefit of BAV, repeat valvuloplasty has emerged as a potential therapeutic strategy. Repeat BAV does have a modest benefit in terms of valve area and symptoms in many patients [2929. Ferguson JJ, Garza RA. Efficacy of multiple balloon aortic valvuloplasty procedures. The Mansfield Scientific Aortic Valvuloplasty Registry Investigators. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;17:1430-5. , 3939. Koning R, Cribier A, Asselin C, Mouton-Schleifer D, Derumeaux G, Letac B. Repeat balloon aortic valvuloplasty. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1992;26:249-54. , 4949. Agarwal A, Kini AS, Attanti S, Lee PC, Ashtiani R, Steinheimer AM, Moreno PR, Sharma SK. Results of repeat balloon valvuloplasty for treatment of aortic stenosis in patients aged 59 to 104 years. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:43-7.

Usefulness of repeat BAV to improve survival]. However, the degree and duration of symptom relief is less with subsequent procedures [4949. Agarwal A, Kini AS, Attanti S, Lee PC, Ashtiani R, Steinheimer AM, Moreno PR, Sharma SK. Results of repeat balloon valvuloplasty for treatment of aortic stenosis in patients aged 59 to 104 years. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:43-7.

Usefulness of repeat BAV to improve survival]. This has led to the investigation of means to inhibit restenosis after BAV. The small RADAR pilot study of external beam radiation applied a few days following BAV found relatively low restenosis rates at 1-year of 21-30% [6363. Pedersen WR, Van Tassel RA, Pierce TA, Pence DM, Monyak DJ, Kim TH, Harris KM, Knickelbine T, Lesser JR, Madison JD, Mooney MR, Goldenberg IF, Longe TF, Poulose AK, Graham KJ, Nelson RR, Pritzker MR, Pagan-Carlo LA, Boisjolie CR, Zenovich AG, Schwartz RS. Radiation following percutaneous balloon aortic valvuloplasty to prevent restenosis (RADAR pilot trial). Catheterization & Cardiovascular Interventions. 2006;68:183-92. ]. The effect was dose-responsive and substantially lower than expected [5353. Letac B, Cribier A, Eltchaninoff H, Koning R, Derumeaux G. Evaluation of restenosis after balloon dilatation in adult aortic stenosis by repeat catheterization. American Heart Journal. 1991;122(1 Pt 1):55-60.

Report on restenosis after BAV]. A potential role for balloon delivery of anti-restenosis pharmaceuticals to the aortic valve leaflets is also being investigated [6464. Spargias K, Milewski K, Debinski M, Buszman PP, Cokkinos DV, Pogge R, Buszman P. Drug delivery at the aortic valve tissues of healthy domestic pigs with a Paclitaxel-eluting valvuloplasty balloon. J Interv Cardiol. 2009;22:291-8. ].

BRIDGE TO DEFINITIVE THERAPY

Several reports have suggested a potential role of BAV prior to surgical aortic valve replacement, an approach which reportedly can have a 2 year survival as high as 92% [4444. Lieberman EB, Bashore TM, Hermiller JB, Wilson JS, Pieper KS, Keeler GP, Pierce CH, Kisslo KB, Harrison JK, Davidson CJ. Balloon aortic valvuloplasty in adults: failure of procedure to improve long-term survival. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;26:1522-8. ]. This may be an attractive strategy for selected patients with uncontrolled heart failure or haemodynamic instability [6565. Doguet F, Godin M, Lebreton G, Eltchaninoff H, Cribier A, Bessou J-P, Litzler P-Y. Aortic valve replacement after percutaneous valvuloplasty. An approach in otherwise inope-rable patients. Eur J CardioThorac Surg 2010;28:394-9.

Place of AVR after BAV in patients initially rejected for AVR due to poor hemodynamic condition or low ejection factor]. However, most symptomatic patients might arguably be better served by avoiding unnecessary delay in proceeding to aortic valve replacement. Similarly BAV has been utilised as a bridge to TAVI as contemporary regulatory, funding and other limitations on this new technology often mean unavoidable delays with definitive treatment. Limited evidence suggests that definitive procedural outcomes may be improved in patients undergoing staged BAV prior to subsequent TAVI.

BAV has also been utilised to reduce the risk of non-cardiac surgery or as temporary relief in the setting of an acute illness when the risk of surgical valve replacement is prohibitive [5959. Eltchaninoff H, Durand E, Borz B, Furuta A, Bejar K, Canville A, Farhat A, Fraccaro C, Godin M, Tron C, Sakhuja R, Cribier A. Balloon aortic valvuloplasty in the era of transcatheter aortic valve replacement: acute and long-term outcomes. Am Heart J. 2014;167:235-40. , 6666. Hayes SN, Holmes DR, Jr., Nishimura RA, Reeder GS. Palliative percutaneous aortic balloon valvuloplasty before noncardiac operations and invasive diagnostic procedures. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 1989;64:753-7. , 6767. Roth RB, Palacios IF, Block PC. Percutaneous aortic balloon valvuloplasty: its role in the management of patients with aortic stenosis requiring major noncardiac surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1989;13:1039-41. , 6868. Desnoyers MR, Salem DN, Rosenfield K, Mackey W, O’Donnell T, Isner JM. Treatment of cardiogenic shock by emergency aortic balloon valvuloplasty. Ann Intern Med. 1988;108:833-5. , 6969. Moreno PR, Jang IK, Newell JB, Block PC, Palacios IF. The role of percutaneous aortic balloon valvuloplasty in patients with cardiogenic shock and critical aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;23:1071-5. , 7070. Kuntz RE, Tosteson AN, Berman AD, Goldman L, Gordon PC, Leonard BM, et al. Predictors of event-free survival after balloon aortic valvuloplasty. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:17-23. ]. Of particular interest is the use of BAV in patients with severe left ventricular dysfunction. On occasion left ventricular function may improve following successful valvuloplasty, facilitating acceptance for more definitive therapy. Low dose dobutamine echocardiography can help in predicting left ventricular functional recovery by assessing contractile reserve [7171. Monin JL, Quéré JP, Monchi M, Petit H, Baleynaud S, Chauvel C, Pop C, Ohlmann P, Lelguen C, Dehant P, Tribouilloy C, Guéret P. Low-gradient aortic stenosis: operative risk stratification and predictors for long-term outcome: a multicenter study using dobutamine stress hemodynamics. Circulation. 2003;108:319-24. ].

BAV indications in the TAVI era

- There is an increasing role of BAV as a bridge to surgical aortic valve replacement or TAVI in patients who present with temporary contra-indications

- Pre-dilatation is performed as the first step of the TAVI procedure

- Non compliant balloons may be also used for post dilatation of balloon-expandable prosthesis at the exact diameter. Post-dilatation may be also performed in order to reduce the severity of residual paravalvular leak after balloon or self-expandable prosthesis.

AS A PART OF TAVI PROCEDURE

At the beginning of TAVI, pre-dilatation of the aortic valve has been regarded as an essential step during the TAVI procedure. Pre-dilatation was supposed to facilitate positioning and deployment of the prosthetic valve in particular for self-expanding valves. However, recent evidence has suggested that aortic valvuloplasty may cause complications and that high success rates may be obtained without prior dilatation of the valve. The feasibility, safety, and efficacy of “direct” TAVI, without pre-dilatation, has been recently reported in a systematic review and meta-analysis [7272. Auffret V, Regueiro A, Campelo-Parada F, Del Trigo M, Chiche O, Chamandi C, Puri R, Rodés-Cabau J. Feasibility, safety, and efficacy of transcatheter aortic valve replacement without balloon predilation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;90:839-850. ]. Mean device success with direct TAVI was 88% with <5% of bail-out techniques. There were no differences between direct and TAVI with pre-dilatation in short-term mortality or cerebrovascular events. Direct TAVI was associated with reduced moderate or severe paravalvular leak post-TAVR but not with a reduced risk of permanent pacemaker implantation. A slight increase in post-dilatation was observed in direct transfemoral-TAVI recipients [7272. Auffret V, Regueiro A, Campelo-Parada F, Del Trigo M, Chiche O, Chamandi C, Puri R, Rodés-Cabau J. Feasibility, safety, and efficacy of transcatheter aortic valve replacement without balloon predilation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;90:839-850. ]. Randomized studies are ongoing to determine the potential benefits of direct TAVR.

AS A PART OF TAVI FOR FAILED SURGICAL PROSTHESIS

Valve-in-valve (ViV) transcatheter aortic valve implantation has been established as a safe and effective treatment for failed surgical bioprosthetic valves in patients at high risk for complications related to reoperation. Patients who undergo ViV TAVI are at risk of patient-prosthesis mismatch, as the transcatheter heart valve is implanted within the ring of the existing surgical bioprosthesis, limiting full expansion and reducing the maximum achievable effective orifice area of the transcatheter heart valve. Importantly, patient-prosthesis mismatch and high residual transvalvular gradients are associated with reduced survival following VIV TAVI. Bioprosthetic valve fracture (BVF) using a high-pressure balloon can be performed to facilitate VIV TAVI. BVF can be performed before or after ViV TAVI by inflation of a high-pressure balloon positioned across the valve ring during rapid ventricular pacing. BVF was recently performed in 20 patients undergoing ViV TAVI with balloon-expandable or self-expanding transcatheter valves in Mitroflow, Carpentier-Edwards Perimount, Magna and Magna Ease, Biocor Epic and Biocor Epic Supra, and Mosaic surgical valves. Successful fracture was noted fluoroscopically when the waist of the balloon released and by a sudden drop in inflation pressure, often accompanied by an audible snap. BVF resulted in a reduction in the mean transvalvular gradient (from 20.5±7.4 to 6.7±3.7 mm Hg, P<0.001) and an increase in valve effective orifice area (from 1.0±0.4 to 1.8±0.6 cm2, P<0.001). No procedural complications were reported [7373. Chhatriwalla AK, Allen KB, Saxon JT, MD; Cohen DJ, Aggarwal S, Hart AJ, Baron SJ, Dvir D, Borkon M. Bioprosthetic valve fracture improves the hemodynamic results of valve-in-valve transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10:e005216. ].