Intervention in mitral stenosis

Mitral stenosis (MS), which still occurs mainly as a result of rheumatic heart disease, remains the most frequent valvular disease in developing countries, where it involves a majority of young adults. The prevalence of rheumatic heart disease in school-age children is estimated at between 1 and 6 per 1,000 in Asia and between 3 and 14% in Africa [11. Chandrashekhar Y, Westaby S, Narula J. Mitral stenosis. Lancet. 2009;374:1271-83. , 22. Iung B, Vahanian A. Epidemiology of acquired valvular heart disease. Can J Cardiol. 2014;30:962-70. , 33. Marijon E, Mirabel M, Celermajer DS, Jouven X. Rheumatic heart disease. Lancet. 2012;379:953-64. ]. Recent data based on systematic echocardiographic examination show that the true prevalence is approximately tenfold higher [44. Marijon E, Ou P, Celermajer DS, Ferreira B, Mocumbi AO, Jani D, Paquet C, Jacob S, Sidi D, Jouven X. Prevalence of rheumatic heart disease detected by echocardiographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:470-6. ]. Conversely, MS is the least frequent valvular disease in industrialised countries: the prevalence of MS was estimated at 0.1% in the US population-based study [55. Nkomo VT, Gardin JM, Skelton TN, Gottdiener JS, Scott CG, Enriquez-Sarano M. Burden of valvular heart diseases: a population-based study. Lancet. 2006;368:1005-11. ] and MS accounted for 9% of single-valve diseases in the Euro Heart Survey [66. Iung B, Baron G, Butchart EG, Delahaye F, Gohlke-Barwolf C, Levang OW, Tornos P, Vanoverschelde J-L, Vermeer F, Boersma E, Ravaud P and Vahanian A. A prospective survey of patients with valvular heart disease in Europe: The Euro Heart Survey on Valvular Heart Disease. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:1231-43. ].

The other main cause of MS is degenerative calcification of the mitral annulus, which is frequent in the elderly but seldom causes significant MS. Rare aetiologies are congenital MS and infiltrative diseases.

Until the first publication by Inoue and co-workers [77. Inoue K, Owaki T, Nakamura T, Kitamura F, Miyamoto N. Clinical application of transvenous mitral commissurotomy by a new balloon catheter. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1984;87:394-402.

The pioneering work] describing percutaneous mitral commissurotomy (PMC) in 1984, surgery was the only treatment for patients with mitral stenosis. Since then, a considerable evolution in the technique has occurred. A large number of patients with a wide range of clinical conditions have now been treated [88. Marijon E, Iung B, Mocumbi AO, Kamblock J, Thanh CV, Gamra H, Esteves C, Palacios IF, Vahanian A. What are the differences in presentation of candidates for percutaneous mitral commissurotomy across the world and do they influence the results of the procedure?. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2008;101:611-7. ], enabling efficacy and risk to be assessed, and long-term results are available, so we are better able to select the most appropriate candidates for treatment by this method.

MECHANISMS OF ACTION

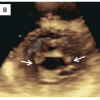

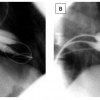

PMC acts in the same way as surgical commissurotomy, by opening the fused commissures [99. Reifart N, Nowak B, Baykut D, Satter P, Bussmann WD, Kaltenbach M. Experimental balloon valvuloplasty of fibrotic and calcific mitral valves. Circulation. 1990;81:1005-11. ] ( Figure 1 ). PMC is of little or no help in cases where the predominant mechanism of MS is restricted valvular mobility caused by valve fibrosis or severe subvalvular disease and where commissural fusion is mild. This latter situation may be encountered after surgical commissurotomy or in non-rheumatic MS, especially in degenerative MS associated with aortic stenosis.

PROCEDURE

The techniques and devices used for PMC have varied over time and from group to group. At the present time, there are two approaches, transvenous and transarterial, and two main techniques, the Inoue technique and the double-balloon technique.

Approaches

Transvenous approach

The transvenous or antegrade approach is more widely used. It is performed through the femoral vein or, exceptionally, through the jugular vein.

Transseptal catheterisation is the first step of the procedure and one of the most crucial. It is described in detail in  View chapter .

View chapter .

In brief, the conditions necessary for safe and successful transseptal catheterisation are: (1) knowledge of the anatomy, which may be modified in patients with mitral stenosis in whom normal geometry has been lost because both atria are enlarged and the convexity of the septum is exaggerated; (2) knowledge of the contraindications; and (3) experience of the operators with continuing performance of the technique.

For the performance of PMC the transseptal puncture is usually in the middle part of the fossa ovalis ,

Most centres use a contralateral arterial femoral approach to position a pigtail catheter on the aortic cusps to help the transseptal puncture; however, in experienced centres, the procedure can be performed using a single venous approach and non-invasive monitoring, which diminishes the risk and discomfort [1010. Gupta S, Schiele F, Xu C, Meneveau N, Seronde MF, Breton V, Bernard Y and Bassand J-P. Simplified percutaneous mitral valvuloplasty with the Inoue balloon. Eur Heart J. 1998;19:610-6. ].

If not guided by transoesophageal echocardiography, which is the case in most PMC transseptal puncture should not be performed if the INR is >2, particularly in patients who have not had a previous cardiac operation, i.e., pericardial opening or window. In patients receiving intravenous heparin this should be discontinued 4 hours before the procedure and can be restarted 3 to 4 hours after. In case of persistent excessive anticoagulation vitamin K should not be given before the procedure in patients who are at high risk for left atrial thrombosis, and PMC should be delayed until a satisfactory level of coagulability has been reached.

During PMC, heparin should be given as a bolus at a dose of around 3 to 5,000 IU after the transseptal catheterisation. To increase safety further, the absence of haemopericardium could be verified using echocardiography before administering heparin after the transseptal puncture.

Devices and techniques

Inoue balloon technique

The Inoue technique was the first one described [77. Inoue K, Owaki T, Nakamura T, Kitamura F, Miyamoto N. Clinical application of transvenous mitral commissurotomy by a new balloon catheter. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1984;87:394-402.

The pioneering work], and a great experience has been acquired worldwide [1212. Vahanian A, Cormier B, Iung B. Percutaneous transvenous mitral commissurotomy using the Inoue balloon: international experience. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1994;2:8-15. ].

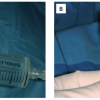

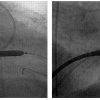

The Inoue balloon, composed of nylon and rubber micromesh, is self-positioning and pressure-extensible. It is large (24 to 30 mm in diameter) and has a low profile (4.5 mm) ( Figure 2 ). The balloon has three distinct parts, each with a specific elasticity, enabling them to be inflated sequentially. This sequence allows fast, stable positioning across the valve. There are four sizes of Inoue balloon available (24, 26, 28 and 30 mm): each is pressure-dependent, so its diameter can be varied by up to 4 mm as required by circumstances ( Figure 3 ).

Inoue recommended the use of a “stepwise dilation technique” under echocardiographic guidance. Balloon size is chosen in accordance with the patient’s height.

Choosing Inoue balloon size

IB: Inoue balloon

* It is advisable to start 1 or 2 mm below the initial balloon size if there is very severe mitral stenosis (valve area <0.5 cm²), or severe commissural calcification

The main steps are as follows:

- Before use the size at full inflation should be checked. Careful venting of the Inoue balloon before use and finally repeated inflations in saline water to flush the last bubbles of air out may decrease the occurrence of air embolism ( Figure 4 ). The first balloon inflation should be performed 4 mm below the maximal balloon size.

- After transseptal catheterisation, the stiff guidewire (0.025, 175m) is introduced into the left atrium. The guidewire should be kept in the cavity of the left atrium (LA), away from the left atrial appendage.

- The femoral entry site and the atrial septum are dilated using a rigid dilator (14 Fr).

- The slenderised Inoue balloon is introduced into the left atrium. If resistance is felt when crossing the skin and subcutaneous tissues, it is necessary to avoid excessive pressure, which may damage the tip of the balloon, by re-dilating the groin entry site with the dilator or, if difficulty persists, inserting a 16 Fr sheath (COOK). If this problem occurs at the level of the septum the balloon should be pulled and rotated in one or other direction and then pushed again. If resistance is still present, it is preferable to dilate the septum with a peripheral angioplasty balloon (6 or 8 mm in diameter, 4 cm long) before another attempt at crossing the inter-atrial septum with the balloon.

- When the Inoue balloon is introduced into the LA, its tip is shortened and the balloon stretching tube and guidewire are withdrawn. The permeability of the catheter is then checked by aspiration and pressure recording.

- The stylet is introduced in AP view and will orient the balloon catheter towards the mitral valve.

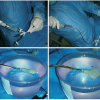

- The Inoue balloon is inflated sequentially in RAO 30° view. First, the distal portion is inflated with 1 or 2 mL of a diluted contrast medium (1 contrast-5 saline). This then acts as a floating balloon catheter when crossing the mitral valve. Crossing of MS is performed by a combination of gently pulling the stylet with an anticlockwise rotation while gently pushing the balloon catheter. If entry into the LV is difficult the “loop manoeuvre” ( Figure 5 ) could be used. Inflation should be pursued only if the balloon is moving freely in the left ventricular cavity directed to the apex. Further inflation should not be performed if the balloon is directed obliquely towards the base of the heart because in such a case it may become trapped in the subvalvular apparatus. Next, the distal part is inflated, and the balloon is pulled back into the mitral orifice. Inflation then occurs at the level of the proximal part and finally in the central portion, with the disappearance of the central waist at full inflation ( Figure 6 ). If it is difficult to maintain the balloon in a stable position across the valve, the inflation can be repeated at a different speed (more quickly, if it was somewhat slow initially, or vice versa). In cases where the patient is tachycardic, slowing the heart rate by using rapid-acting beta-blockers may also be helpful. The inflation/deflation time should be short (3 to 4 sec).

- When the balloon is deflated, the stylet is pulled back and the balloon is withdrawn into the left atrium.

- If the echocardiographic evaluation shows that the result is insufficient the balloon size is increased up to the maximum size in 1 mm increments according to echocardiographic monitoring.

- When PMC is considered to be finished, the guidewire and the balloon stretching tube should be reintroduced into the Inoue balloon in order to slenderise it fully before withdrawal. This is done in AP view. Penetration of the guidewire into the left atrial appendage should be avoided when readvancing the guidewire. Before pulling the balloon across the inter-atrial septum, the guidewire needs to be pulled so that only its soft part is left external in order to avoid “a cutting effect” which may occur if the stiff part of the guidewire is out of the tip of the balloon during the manoeuvre.

- The balloon and guidewire are withdrawn as a single unit to the surface of the skin and manual compression is started.

How to solve problems when using the Inoue balloon

IB: Inoue balloon

RA: right atrium

LV: left ventricle

Double-balloon technique is now very seldom used

Briefly, the technique is as follows. After transseptal catheterisation, the left ventricle is catheterised with the use of a floating balloon catheter. One or two long exchange guidewires are positioned in the apex of the left ventricle or, less frequently, in the ascending aorta. The inter-atrial septum is dilated with the use of a peripheral angioplasty balloon (8 or 6 mm in diameter). Finally, the balloons (15 to 20 mm in diameter) are positioned across the mitral valve [1313. Al Zaibag M, Ribeiro PA, Al Kasab S, Al Fagih MR. Percutaneous double-balloon mitral valvotomy for rheumatic mitral-valve stenosis. Lancet. 1986;1:757-61. , 1414. Palacios IF, Sanchez PL, Harrell LC, Weyman AE, and Block PC. Which patients benefit from percutaneous mitral balloon valvuloplasty? Prevalvuloplasty and postvalvuloplasty variables that predict long-term outcome. Circulation. 2002;105:1465-71. ]. ( Figure 7 ).

The Multi-Track system is a more recent refinement of the double-balloon technique that uses a monorail system, requiring the presence of only one guidewire and easing the performance of the dilation compared with the standard double-balloon technique. Reported clinical experience with this device is limited [1515. Bonhoeffer P, Hausse A, Yonga G, Yuko-Jowi C, Aggoun Y, Saliba Z, Ferreira B, Sidi D, Kachaner J. Technique and results of percutaneous mitral valvuloplasty with the multi-track system. J Interv Cardiol. 2000;13:263-8. ] ( Figure 8 ).

The metallic commissurotome has now been abandonned ( Figure 9) [1616. Cribier A, Eltchaninoff H, Carlot R. Percutaneous mechanical mitral commissurotomy with the metallic valvotome: Detailed technical aspect and overview of the results of the multi-center registry 882 patients. J Interv Cardiol. 2000;13:255-6. ].

Data currently available comparing the double-balloon and Inoue techniques suggest that the Inoue technique significantly eases the procedure and has equivalent efficacy and lower risk. In fact, the Inoue technique has become, almost exclusively, the method used worldwide. Finally, even though randomised studies are lacking and intraprocedural echocardiography lacks practicality, the stepwise technique under echocardiographic guidance certainly allows the best use of the mechanical properties of the Inoue balloon and therefore optimises the results.

Monitoring/guiding of the procedure

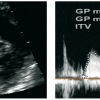

There are two ways to monitor the procedure and assess immediate results in the catheterisation laboratory: haemodynamics and echocardiography. Haemodynamic monitoring has several limitations: an arterial line is necessary; measurements of cardiac output are inaccurate if performed using a Swan-Ganz catheter due to the presence of inter-atrial shunting; their interpretation is difficult in patients in atrial fibrillation and low cardiac output or in cases with acute changes in heart rate or systemic pressure. Echocardiography , which is now the most popular imaging technique ,provides essential information since it can be used to guide transseptal catheterisation, provides information on the course of the mitral opening, which is of utmost importance when using the stepwise Inoue technique, and finally enables detection of early complications.

Usually, transseptal catheterisation is performed under fluoroscopic guidance and pressure monitoring. Echocardiography is not systematic during transseptal catheterisation; however, it has the potential to enhance its safety, especially in the early part of the operator’s experience. This has been done primarily with the transoesophageal approach (TOE), which is superior to the transthoracic approach (TTE) for imaging the inter-atrial septum. Nevertheless, the performance of the transoesophageal approach is not easy in the catheterisation laboratory since it requires general anaesthesia in most cases and should probably be restricted to cases in which technical difficulties are encountered. Intracardiac echocardiography (ICE) is currently considered the imaging tool of choice in several catheterisation centres to guide transseptal puncture because it may be used without additional operators or general anaesthesia, although the price of the device is a serious limitation in most places [1717. Silvestry FE, Kerber RE, Brook MM, Carroll JD, Eberman KM, Goldstein SA, Herrmann HC, Homma S, Mehran R, Packer DL, Parisi AF, Pulerwitz T, Seward JB, Tsang TSM, Wood MA. Echocardiography-guided interventions. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2009;22:213-31. ]. Real-time 3D transoesophageal technique (RT 3D TOE) may further improve the visualisation of the septum and assessment of the tenting during the septal puncture [1818. Perk G, Lang RM, Garcia-Fernandez MA, Lodato J, Sugeng L, Lopez J, Knight BP, Messika-Zeitoun D, Shah S, Slater J, Brochet E, Varkey M, Hijazi Z, Marino N, Ruiz C, Kronzon I. Use of real time three dimensional transesophageal echocardiography in intracardiac catheter based interventions. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2009;22:865-82. ].

Transthoracic echocardiography is the preferred technique for monitoring of the following steps of the procedure. Transoesophageal guidance under general anaesthesia, although performed systematically in some centres, is restricted to cases where difficulty is encountered or in pregnant patients to reduce radiation exposure. TOE provides excellent views of the balloon position as it is advanced into the mitral orifice. Real-time three-dimensional technique has the added advantage of providing an “en face” view of the mitral valve, allowing better visualisation of the trajectory and positioning of the balloon before inflation. Although the visualisation of the mitral orifice is less optimal with ICE than with TOE, adequate views may be obtained from the right ventricle.

The following recommendations have been suggested for evaluating the results of the procedure. Use of the mean left atrial pressure and mean valve gradient can be criticised because of variations that may occur, particularly with respect to changes in the heart rate or cardiac output. The accuracy of Doppler measurements during PMC is low, so planimetry from 2D/3D echocardiography appears to be the method of choice if it is technically feasible. Colour Doppler assessment is the method of choice for sequential evaluation of changes in the degree of regurgitation. The commissural opening, which is the main parameter, is usually assessed in the parasternal short-axis view during TTE. Real-time three-dimensional echocardiography is the most accurate method for assessing the degree of opening using short-axis views [1919. Messika-Zeitoun D, Brochet E, Holmin C, Rosenbaum D, Cormier B, Serfaty JM, Iung B, Vahanian A. Three-dimensional evaluation of the mitral valve area and commissural opening before and after percutaneous mitral commissurotomy in patients with mitral stenosis. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:72-9.

This study shows the usefulness of 3D echocardiography in the evaluation of the commissural areas] or real-time three-dimensional TOE en face views which may provide further information regarding the extent of the commissural opening.

The following criteria have been proposed for the desired endpoint of the procedure ( Figure 10 ):

Criteria for ending PMC

- Valve area >1 cm²/m² BSA, and

- complete commissural opening in at least 1 commissure, or

- appearance or increase of regurgitation >1+

Special caution is needed in: elderly patients;; very severe stenosis; extensive subvalvular lesions; nodular commissural calcification; if asymmetric mode of opening ; and during pregnancy BSA: body surface area

(1) mitral valve area of more than 1 cm2/m2 of the body surface area; (2) complete opening of at least one commissure; or (3) appearance or incremental increase of regurgitation greater than 1/4, especially if it is associated with a visible mechanism of MR such as chordal rupture or valve tearing. It is vital that the strategy be tailored to the individual circumstances, taking into account clinical factors together with anatomic factors and the cumulative data of periprocedural monitoring. For example, balloon size, increments of size, and expected final valve area are smaller in certain clinical subsets such as in elderly patients or pregnant patients where the need for emergency surgery is of concern, and in the presence of tight mitral stenosis, extensive valve or subvalvular disease, or nodular commissural calcification. In addition, an asymmetric mode of opening during the procedure should lead to caution.

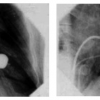

Evaluation of the results

After the procedure, the most accurate evaluation of valve area is achieved by echocardiography ( Figure 11 ). To allow for the slight loss during the first 24 hours, this should be performed 1 to 2 days after PMC when the valve area may be calculated by planimetry or by the half-pressure time or continuity equation method. Finally, the degree of regurgitation may be assessed by colour Doppler flow. The most sensitive method for assessing shunting is colour Doppler flow, especially when TOE is used. In current practice, the use of TOE at this stage is restricted to patients with severe mitral regurgitation to evaluate the mechanisms.

Role of experience

The importance of training for PMC is demonstrated by the comparison of early and late experiences in the same groups or of large-volume centre reports and multicentre studies, including centres with variable experience. The incidence of technical failures and complications, particularly those related to transseptal catheterisation, is clearly related to the operator’s experience [2020. Iung B, Nicoud-Houel A, Fondard O, Akoudad H, Haghighat T, Brochet E, Garbarz E, Cormier B, Baron G, Luxereau P and Vahanian A. Temporal trends in percutaneous mitral commissurotomy over a 15-year period. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:701-7. ].

Even though the considerable simplification resulting from use of the Inoue balloon may lead to a false sense of security when applying the technique, PMC should be restricted to teams that have extensive experience with transseptal catheterisation and are able to perform an adequate number of procedures. The interventionists who perform PMC must also be able to perform emergency pericardiocentesis.

IMMEDIATE RESULTS

Failures

The failure rate ranges from 1% to 17% [88. Marijon E, Iung B, Mocumbi AO, Kamblock J, Thanh CV, Gamra H, Esteves C, Palacios IF, Vahanian A. What are the differences in presentation of candidates for percutaneous mitral commissurotomy across the world and do they influence the results of the procedure?. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2008;101:611-7. , 1111. Stefanadis C, Stratos C, Lambrou S, Bahl VK, Cokkinos DV, Voudris VA, Foussas SG, Tsioufis CP, Toutouzas PK. Retrograde nontransseptal balloon mitral valvuloplasty: Immediate results and intermediate long-term outcome in 441 cases. A multi-center experience. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32:1009-16. , 1212. Vahanian A, Cormier B, Iung B. Percutaneous transvenous mitral commissurotomy using the Inoue balloon: international experience. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1994;2:8-15. , 1313. Al Zaibag M, Ribeiro PA, Al Kasab S, Al Fagih MR. Percutaneous double-balloon mitral valvotomy for rheumatic mitral-valve stenosis. Lancet. 1986;1:757-61. , 1414. Palacios IF, Sanchez PL, Harrell LC, Weyman AE, and Block PC. Which patients benefit from percutaneous mitral balloon valvuloplasty? Prevalvuloplasty and postvalvuloplasty variables that predict long-term outcome. Circulation. 2002;105:1465-71. , 1515. Bonhoeffer P, Hausse A, Yonga G, Yuko-Jowi C, Aggoun Y, Saliba Z, Ferreira B, Sidi D, Kachaner J. Technique and results of percutaneous mitral valvuloplasty with the multi-track system. J Interv Cardiol. 2000;13:263-8. , 1616. Cribier A, Eltchaninoff H, Carlot R. Percutaneous mechanical mitral commissurotomy with the metallic valvotome: Detailed technical aspect and overview of the results of the multi-center registry 882 patients. J Interv Cardiol. 2000;13:255-6. , 2020. Iung B, Nicoud-Houel A, Fondard O, Akoudad H, Haghighat T, Brochet E, Garbarz E, Cormier B, Baron G, Luxereau P and Vahanian A. Temporal trends in percutaneous mitral commissurotomy over a 15-year period. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:701-7. , 2121. Arora R, Kalra GS, Singh S, Mukhopadhyay S, Kumar A, Mohan JC, and Nigam M. Percutaneous transvenous mitral commissurotomy: immediate and long-term follow- up results. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2002;55: 450-6. , 2222. Iung B, Cormier B, Ducimetiere P, Porte JM, Nallet O, Michel PL, Acar J and Vahanian A. Immediate results of percutaneous mitral commissurotomy. A predictive model on a series of 1514 patients. Circulation. 1996; 94:2124-30. , 2323. Ben Farhat M, Betbout F, Gamra H, Maatouk F, Ben-Hamda K, Abdellaoui M, Hammami S, Jarrar M, Addad F, Dridi Z. Predictors of long-term event-free survival and of freedom from restenosis after percutaneous balloon mitral commissurotomy. Am Heart J. 2001;142:1072-79. , 2424. Chen CR, Cheng TO. Percutaneous balloon mitral valvuloplasty by the Inoue technique: A multicenter study of 4832 patients in China. Am Heart J. 1995; 129:1197-202. , 2626. Badheka AO, Shah N, Ghatak A, Patel NJ, Chothani A, Mehta K, Singh V, Patel N, Grover P, Deshmukh A, Panaich SS, Savani GT, Bhalara V, Arora S, Rathod A, Desai H, Kar S, Alfonso C, Palacios IF, Grines C, Schreiber T, Rihal CS, Makkar R, Cohen MG, O'Neill W, de Marchena E.. Balloon mitral valvuloplasty in the United States: a 13-year perspective. Am J Med. 2014;127:1126 e1-12.

A large muticentre study assessing the complications observed in the US]. Failure is mostly caused by an inability to puncture the atrial septum or to position the balloon correctly across the valve. Most failures occur early in the investigator’s experience. Failures can also result from unfavourable anatomy, such as severe atrial or predominant subvalvular stenosis. If the operator feels that valve crossing may be related to the either too high or too anterior transseptal puncture, it may be necessary to redo the transseptal puncture in a more appropriate position. However, a second attempt at transseptal puncture is not recommended if full heparinisation has already been administered. In such cases it is advisable to reschedule PMC. For this reason, in some experienced teams heparin is only given after the first inflation.

Haemodynamics

PMC usually provides an increase of more than 100% in valve area ( Table 1 ). The improvement in valve function results in an immediate decrease in left atrial pressure and a slight increase in cardiac index. A gradual decrease in pulmonary arterial pressure and pulmonary vascular resistance is seen. High pulmonary vascular resistance continues to decrease in the absence of restenosis [2525. Krishnamoorthy KM, Dash PK, Radhakrishnan S, Shrivastava S. Response of different grades of pulmonary artery hypertension to balloon mitral valvuloplasty. Am J Cardiol. 2002;90:1170-73. ].

PMC has a beneficial effect on exercise capacity.

Complications

Generally speaking, the occurrence of complications can be patient-related due to their clinical and anatomical condition or else operator-related ( Table 2) [2626. Badheka AO, Shah N, Ghatak A, Patel NJ, Chothani A, Mehta K, Singh V, Patel N, Grover P, Deshmukh A, Panaich SS, Savani GT, Bhalara V, Arora S, Rathod A, Desai H, Kar S, Alfonso C, Palacios IF, Grines C, Schreiber T, Rihal CS, Makkar R, Cohen MG, O'Neill W, de Marchena E.. Balloon mitral valvuloplasty in the United States: a 13-year perspective. Am J Med. 2014;127:1126 e1-12.

A large muticentre study assessing the complications observed in the US, 2727. Meneveau N, Schiele F, Seronde MF, Breton V, Gupta S, Bernard Y, and Bassand JP. Predictors of event-free survival after percutaneous mitral commissurotomy. Heart. 1998;80:359-64. , 2828. Neumayer U, Schmidt HK, Fassbender D, Mannebach H, Bogunovic N, Horstkotte D. Early (three-month) results of percutaneous mitral valvotomy with the Inoue balloon in 1,123 consecutive patients comparing various age groups. Am J Cardiol. 2002;90:190-3. , 2929. Jneid H, Cruz-Gonzalez I, Sanchez-Ledesma M, Maree AO, Cubeddu RJ, Leon ML, Rengifo-Moreno P, Otero JP, Inglessis I, Sanchez PL, and Palacios IF. Impact of pre- and post-procedural mitral regurgitation on outcomes after percutaneous mitral valvuloplasty for mitral stenosis. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104:1122-27. , 3030. Varma PK, Theodore S, Neema PK, Ramachandran P, Sivadasanpillai H, Kumar Nair K, and Neelakandhan KS. Emergency surgery after percutaneous transmitral commissurotomy: Operative versus echocardiographic findings, mechanisms of complications, and outcomes. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;130:772-6. , 3131. Zimet AD, Almeida AA, Harper RW, Smolich JJ, Goldstein J, Shardey GC, and Smith JA. Predictors of surgery after percutaneous mitral valvuloplasty. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;82:828-33. , 3232. Choudhary SK, Talwar S, Venugopal P. Severe mitral regurgitation after percutaneous transmitral commissurotomy: underestimated subvalvular disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;131:927; author reply 927-8. , 3333. Cequier A, Bonan R, Dyrda I, Crepeau J, Dethy M, and Waters D. Atrial shunting after percutaneous mitral valvuloplasty. Circulation. 1990;81:1190. ].

Mortality

The main causes of death are massive haemopericardium or the poor condition of the patient. The latter condition is often a factor in end-stage patients, such as elderly patients where PMC is attempted as a palliative procedure or in emergency cases performed in patients with pulmonary oedema or, very occasionally, in cardiogenic shock. The fatality rate ranges from 0% to 3%.

Haemopericardium

Haemopericardium may be related to transseptal catheterisation or to left ventricular perforation by the guidewires or the balloons. Its incidence varies from 0.5% to 12%. Haemopericardium usually has immediate clinical consequences resulting in tamponade.

Haemopericardium related to the transseptal puncture mostly occurs when the operator is less experienced. Unfavourable patient characteristics such as severe atrial enlargement or severe thoracic deformity also increase risk. Furthermore, the occurrence of haemopericardium may be technique-dependent. The double-balloon technique and its variants the Multi-Track technique or the metallic commissurotome carry a higher risk than the Inoue technique, where the risk of left ventricular perforation is virtually eliminated.

Haemopericardium should always be suspected when hypotension occurs during PMC and echocardiography should be performed urgently before deterioration occurs. This stresses the importance of the immediate availability of echocardiography when performing PMC.

Haemopericardium requires immediate pericardiocentesis ideally performed under echocardiographic guidance after reversal of anticoagulation by protamine injection. If this is successful, PMC can be reattempted and the patient should be closely monitored. In most cases, haemopericardium due to transseptal catheterisation can be managed by pericardiocentesis especially when it results from only an incorrect puncture by the transseptal needle.

Embolism

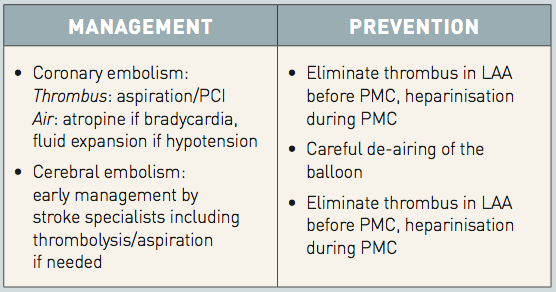

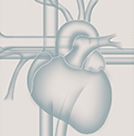

Embolism may be due to a thrombus that was pre-existing, usually in the left atrial appendage, or which developed during the procedure. It may also be due to air leaking from the balloon or, very rarely, to calcium. Embolism is encountered in 0.5% to 5% of cases. Although the incidence of thrombotic embolism is low, its potential consequences are severe and all possible precautions should be taken to prevent it. Cerebral embolism usually results in a stroke. Coronary embolism leads to transient ST segment elevation in inferior ECG leads, which is well tolerated when it is due to microbubbles of air which can occur when using the Inoue balloon and which will resolve spontaneously. If it is due to embolisation of a large quantity of air, such as when the balloon ruptures with the double-balloon technique, it may lead to vagal reaction and hypotension, which requires appropriate treatment. If a coronary occlusion is present, coronary angioplasty could be performed, while thromboaspiration may be an appealing alternative.

The treatment of cerebral thrombotic embolism should be in collaboration with a stroke centre. Cerebral imaging should be performed on an emergency basis to rule out haemorrhage, then intra-arterial fibrinolytic therapy should be administered early in the absence of contraindication.

Management and prevention of embolism during PMC

LAA: left atrial appendage; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; PMC: percutaneous mitral commissurotomy

Severe mitral regurgitation

Severe mitral regurgitation is rare but represents an ever-present risk [2020. Iung B, Nicoud-Houel A, Fondard O, Akoudad H, Haghighat T, Brochet E, Garbarz E, Cormier B, Baron G, Luxereau P and Vahanian A. Temporal trends in percutaneous mitral commissurotomy over a 15-year period. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:701-7. , 2121. Arora R, Kalra GS, Singh S, Mukhopadhyay S, Kumar A, Mohan JC, and Nigam M. Percutaneous transvenous mitral commissurotomy: immediate and long-term follow- up results. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2002;55: 450-6. , 2222. Iung B, Cormier B, Ducimetiere P, Porte JM, Nallet O, Michel PL, Acar J and Vahanian A. Immediate results of percutaneous mitral commissurotomy. A predictive model on a series of 1514 patients. Circulation. 1996; 94:2124-30. , 2323. Ben Farhat M, Betbout F, Gamra H, Maatouk F, Ben-Hamda K, Abdellaoui M, Hammami S, Jarrar M, Addad F, Dridi Z. Predictors of long-term event-free survival and of freedom from restenosis after percutaneous balloon mitral commissurotomy. Am Heart J. 2001;142:1072-79. , 2424. Chen CR, Cheng TO. Percutaneous balloon mitral valvuloplasty by the Inoue technique: A multicenter study of 4832 patients in China. Am Heart J. 1995; 129:1197-202. , 2626. Badheka AO, Shah N, Ghatak A, Patel NJ, Chothani A, Mehta K, Singh V, Patel N, Grover P, Deshmukh A, Panaich SS, Savani GT, Bhalara V, Arora S, Rathod A, Desai H, Kar S, Alfonso C, Palacios IF, Grines C, Schreiber T, Rihal CS, Makkar R, Cohen MG, O'Neill W, de Marchena E.. Balloon mitral valvuloplasty in the United States: a 13-year perspective. Am J Med. 2014;127:1126 e1-12.

A large muticentre study assessing the complications observed in the US, 2828. Neumayer U, Schmidt HK, Fassbender D, Mannebach H, Bogunovic N, Horstkotte D. Early (three-month) results of percutaneous mitral valvotomy with the Inoue balloon in 1,123 consecutive patients comparing various age groups. Am J Cardiol. 2002;90:190-3. , 2929. Jneid H, Cruz-Gonzalez I, Sanchez-Ledesma M, Maree AO, Cubeddu RJ, Leon ML, Rengifo-Moreno P, Otero JP, Inglessis I, Sanchez PL, and Palacios IF. Impact of pre- and post-procedural mitral regurgitation on outcomes after percutaneous mitral valvuloplasty for mitral stenosis. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104:1122-27. , 3030. Varma PK, Theodore S, Neema PK, Ramachandran P, Sivadasanpillai H, Kumar Nair K, and Neelakandhan KS. Emergency surgery after percutaneous transmitral commissurotomy: Operative versus echocardiographic findings, mechanisms of complications, and outcomes. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;130:772-6. , 3131. Zimet AD, Almeida AA, Harper RW, Smolich JJ, Goldstein J, Shardey GC, and Smith JA. Predictors of surgery after percutaneous mitral valvuloplasty. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;82:828-33. , 3232. Choudhary SK, Talwar S, Venugopal P. Severe mitral regurgitation after percutaneous transmitral commissurotomy: underestimated subvalvular disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;131:927; author reply 927-8. ]. Surgical findings [3030. Varma PK, Theodore S, Neema PK, Ramachandran P, Sivadasanpillai H, Kumar Nair K, and Neelakandhan KS. Emergency surgery after percutaneous transmitral commissurotomy: Operative versus echocardiographic findings, mechanisms of complications, and outcomes. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;130:772-6. ] have shown that it is most often related to non-commissural leaflet tearing, which could be associated with chordal rupture ( Figure 12 ). In these cases, one or both commissures are often too tightly fused to be split. Severe mitral regurgitation may also be due to excessive commissural splitting or, in very rare cases, rupture of a papillary muscle. The majority of cases of severe mitral regurgitation occur in patients with unfavourable anatomy. The frequency of severe mitral regurgitation ranges from 2% to 19%.

Subsequent surgical treatment is usually necessary because the prognosis of patients with severe mitral regurgitation after PMC is usually poor, with secondary objective deterioration and a lack of symptom alleviation. In most cases, valve replacement is required because of the severity of the underlying valve disease. Conservative surgery has been successfully performed in cases of less severe valve deformity.

The precise timing of intervention should be based on clinical tolerance, the mechanisms of MR, changes in pulmonary pressures, and surgical risk. If the clinical condition is stable and there is no newly appeared or recently increased severe pulmonary hypertension, mitral regurgitation is initially well-tolerated and surgery can in most cases be performed on a scheduled basis. In other cases urgent surgery should be considered.

At the present stage, the occurrence of severe mitral regurgitation remains largely unpredictable for a given patient [3131. Zimet AD, Almeida AA, Harper RW, Smolich JJ, Goldstein J, Shardey GC, and Smith JA. Predictors of surgery after percutaneous mitral valvuloplasty. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;82:828-33. ] and its development depends more on the distribution of morphologic changes than on their severity. The available data suggest, but do not prove, that the stepwise Inoue technique combined with echocardiographic monitoring is likely to decrease the incidence of severe regurgitation, even if it does not eliminate it.

Management and prevention of severe mitral regurgitation during PMC

MR: mitral regurgitation

Rescue surgery

Although urgent surgery (within 24 hours) is seldom needed for complications (<1%), it may be required for massive haemopericardium resulting from left ventricular perforation intractable to treatment by pericardiocentesis. According to circumstances this could be drainage of the pericardial effusion alone or could also include valve surgery.

Less frequently, severe mitral regurgitation, leading to haemodynamic collapse or refractory pulmonary oedema, may necessitate emergency surgery with the support of an intra-aortic balloon pump en route to the operating room.

The exact arrangement for surgical back-up varies from institution to institution, according to the severity of the condition being treated and the experience of the cardiologic and surgical teams.

Inter-atrial shunts

These shunts are usually small and without consequence since most of them will disappear on follow-up after successful PMC because of a reduced inter-atrial pressure gradient. In rare circumstances, right to left shunts may occur in patients with severe pulmonary hypertension when PMC is not successful and may lead to hypoxaemia [3333. Cequier A, Bonan R, Dyrda I, Crepeau J, Dethy M, and Waters D. Atrial shunting after percutaneous mitral valvuloplasty. Circulation. 1990;81:1190. ].

Management of hypotension during PMC

- Look at ECG:Bradycardia +/- ST elevation: air embolism is likely (specific treatment)

- Look at LA pressure:High V wave: severe MR is likely (specific treatment)

- Look at echocardiography:Tamponade: drainage

Severe MR: (specific treatment)

Segmental LV dysfunction: coronary embolism (specific treatment)

LA: left atrium; MR: mitral regurgitation

The frequency of inter-atrial shunts varies from 10% to 90% depending on the technique used for detection. Use of the Inoue technique has significantly decreased the incidence of this complication in comparison with the other techniques. Surgery has very seldom been necessary because of inter-atrial shunting. On the other hand, if surgery is needed for unsuccessful PMC or restenosis, the inter-atrial septum should be looked at and septal tears sutured at the time of surgery. No cases of percutaneous closure of such defects have been reported to our knowledge and such a procedure is unlikely to be successful because the inter-atrial shunts are not due to defects similar to patent foramen ovale or congenital atrial septal defects but to longitudinal tears.

Other complications

Atrial fibrillation rarely occurs during the procedure. When it does, it is usually transient and resolves within a few hours under medical treatment. In rare cases, it requires electric countershock a few days later.

The incidence of transient, complete heart block is rare (<1%) and exceptionally requires implantation of a permanent pacemaker.

Vascular complications are the exception when using the antegrade or transvenous approach.

Endocarditis is extremely rare and does not justify prophylaxis before the procedure. The risk is higher when balloons are reused: this occurs in many centres in developing countries. The same holds true for transmissible infections such as hepatitis or HIV.

Predictors of immediate results

Evaluation of immediate results is mainly based on haemodynamic criteria. The definition of good immediate results varies from series to series. The two definitions frequently employed are: 1) a final valve area larger than 1.5 cm2 and an increase in valve area of at least 25%; or 2) a final valve area larger than 1.5 cm2 without mitral regurgitation greater than 2/4.

Anatomy was initially thought to be the main, if not the only, predictor of results, but it later appeared to be only a relative predictor. In fact, prediction of results is multifactorial [1414. Palacios IF, Sanchez PL, Harrell LC, Weyman AE, and Block PC. Which patients benefit from percutaneous mitral balloon valvuloplasty? Prevalvuloplasty and postvalvuloplasty variables that predict long-term outcome. Circulation. 2002;105:1465-71. , 2222. Iung B, Cormier B, Ducimetiere P, Porte JM, Nallet O, Michel PL, Acar J and Vahanian A. Immediate results of percutaneous mitral commissurotomy. A predictive model on a series of 1514 patients. Circulation. 1996; 94:2124-30. ]. Several studies have shown that, in addition to morphologic factors, preoperative variables such as age, history of surgical commissurotomy, functional class, small mitral valve area, presence of mitral regurgitation before valvuloplasty, sinus rhythm, pulmonary artery pressure, and presence of severe tricuspid regurgitation, as well as procedural factors such as balloon size, are all independent predictors of the immediate results.

Identification of these variables linked to outcome has enabled models to be developed with a high sensitivity of prediction. Nevertheless, the specificity is low, indicating insufficient prediction of poor immediate results. This low specificity is particularly true with regard to the lack of accurate prediction of severe mitral regurgitation.

LONG-TERM RESULTS

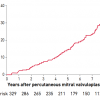

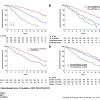

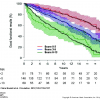

We are now able to analyse follow-up data up to over 20 years, which represents long-term results [3434. Fawzy ME, Shoukri M, Al Buraiki J, Hassan W, El Widaal H, Kharabsheh, S, Al Sanei A, Canver C. Seventeen years’ clinical and echocardiographic follow up of mitral balloon valvuloplasty in 520 patients, and predictors of long-term outcome. J Heart Valve Dis. 2007;16:454-60. , 3535. Tanabe Y, Oshima M, Suzuki M, Takahashi M. Determinants of delayed improvement in exercise capacity after percutaneous transvenous mitral commissurotomy. Am Heart J. 2000;139:889-94. , 3636. Cohen DJ, Kuntz RE, Gordon SP, Piana RN, Safian RD, McKay RG, Baim DS, Grossman W, and Diver DJ. Predictors of long-term outcome after percutaneous balloon mitral valvuloplasty. N Engl J Med. 1992;327: 1329-35. , 3737. Dean LS, Mickel M, Bonan R, Holmes DR Jr., O’Neill WW, Palacios IF, Rahimtoola S, Slater JN, Davis K, and Ward Kennedy J. Four-year follow-up of patients undergoing percutaneous balloon mitral commissurotomy. A report from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Balloon Valvuloplasty Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;28:1452-7. , 3838. Tomai F, Gaspardone A, Versaci F, Ghini AS, Altamura L, De Luca L, Gioffrè G, Gioffrè PA.. Twenty year follow-up after successful percutaneous balloon mitral valvuloplasty in a large contemporary series of patients with mitral stenosis. Int J Cardiol. 2014;177:881-5. , 3939. Bouleti C, Iung B, Laouénan C, Himbert D, Brochet E, Messika-Zeitoun D, Détaint D, Garbarz E, Cormier B, Michel PL, Mentré F, Vahanian A. Late results of percutaneous mitral commissurotomy up to 20 years. Development and validation of a risk score predicting late functional results from a series of 912 patients. Circulation. 2012;125:2119-27

This study shows the longest follow up available after PMC and demonstrates the usefulness of a scoring system for the prediction of long term results., 4040. Cruz-Gonzalez I, Sanchez-Ledesma M, Sanchez PL, Martin-Moreiras J, Jneid H, Rengifo-Moreno P, Inglessis-Azuaje I, Maree AO, Palacios IF. Predicting success and long-term outcomes of percutaneous mitral valvuloplasty: a multifactorial score. Am J Med. 2009;122:581.

This study illustrates the multifactorial nature of the prediction of the results of percutaneous mitral commissurotomy, 4141. Ramondo A, Napodano M, Fraccaro C, Razzolini R, Tarantini G, and Iliceto S. Relation of patient age to outcome of percutaneous mitral valvuloplasty. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:1493-500. , 4242. Kim MJ, Song JK, Song JM, Kang DH, Kim YH, Whan Lee C, Hong MK, Kim JJ, Park SW, and Park SJ. Long-term outcomes of significant mitral regurgitation after percutaneous mitral valvuloplasty. Circulation. 2006;114:2815-22. , 4343. Kang DH, Park SW, Song JK, Kim HS, Hong MK, Kim JJ, and Park SJ. Long-term clinical and echocardiographic outcome of percutaneous mitral valvuloplasty: Randomized comparison of Inoue and double-balloon techniques. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:169-75. , 4444. Song JK, Song JM, Kang DH, Yun SC, Park DW, Lee SW, Kim Y-H, Lee CW, Hong MK, Kim JJ, Park SW and Park SJ. Restenosis and adverse clinical events after successful percutaneous mitral valvuloplasty: immediate post-procedural mitral valve area as an important prognosticator. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:1254-62.

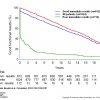

A careful analysis of the incidence and the predictors of restenosis after percutaneous mitral commissurotomy, 4545. Messika-Zeitoun D, Blanc J, Iung B, Brochet E, Cormier B, Himbert D and Vahanian A. Impact of degree of commissural opening after percutaneous mitral commissurotomy on long-term outcome. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2:1-7. , 4646. Wang A, Krasuski RA, Warner JJ, Pieper K, Kisslo KB, Bashore TM, and Harrison JK. Serial echocardiographic evaluation of restenosis after successful percutaneous mitral commissurotomy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:328-34. , 4747. Langerveld J, Thijs Plokker HW, Ernst SM, Kelder JC, Jaarsma W. Predictors of clinical events or restenosis during follow-up after percutaneous mitral balloon valvotomy. Eur Heart J. 1999;20:519-26. , 4848. Hernandez R, Bañuelos C, Alfonso F, Goicolea J, Fernández-Ortiz A, Escaned J, Azcona L, Almeria C, and Macaya C. Long-term clinical and echocardiographic follow-up after percutaneous mitral valvuloplasty with the Inoue balloon. Circulation. 1999;99:1580-6. ]. However, few series show follow-up of over 20 years and these data are getting close to the longest surgical follow-up ( Table 3 and Figure 13 ).

In clinical terms, which are the most widely used, the overall midterm results of PMC are encouraging, showing high survival rates. However, it should be taken into account that the natural history of mitral stenosis is characterised by a relatively low mortality, apart from patients in NYHA class IV. Thus, late results of PMC are generally assessed by composite endpoints combining survival, absence of valvular reintervention and, in certain series, functional status with an event-free survival ranging from 35% to 70% after 10 to 15 years.

Prediction of long-term results is also multifactorial [1414. Palacios IF, Sanchez PL, Harrell LC, Weyman AE, and Block PC. Which patients benefit from percutaneous mitral balloon valvuloplasty? Prevalvuloplasty and postvalvuloplasty variables that predict long-term outcome. Circulation. 2002;105:1465-71. , 3939. Bouleti C, Iung B, Laouénan C, Himbert D, Brochet E, Messika-Zeitoun D, Détaint D, Garbarz E, Cormier B, Michel PL, Mentré F, Vahanian A. Late results of percutaneous mitral commissurotomy up to 20 years. Development and validation of a risk score predicting late functional results from a series of 912 patients. Circulation. 2012;125:2119-27

This study shows the longest follow up available after PMC and demonstrates the usefulness of a scoring system for the prediction of long term results., 4040. Cruz-Gonzalez I, Sanchez-Ledesma M, Sanchez PL, Martin-Moreiras J, Jneid H, Rengifo-Moreno P, Inglessis-Azuaje I, Maree AO, Palacios IF. Predicting success and long-term outcomes of percutaneous mitral valvuloplasty: a multifactorial score. Am J Med. 2009;122:581.

This study illustrates the multifactorial nature of the prediction of the results of percutaneous mitral commissurotomy], based on clinical variables such as age [4141. Ramondo A, Napodano M, Fraccaro C, Razzolini R, Tarantini G, and Iliceto S. Relation of patient age to outcome of percutaneous mitral valvuloplasty. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:1493-500. ], valve anatomy as assessed by echocardiography scores, factors related to the evolutionary stage of the disease (i.e., higher NYHA class before valvuloplasty), history of previous commissurotomy, severe tricuspid regurgitation, cardiomegaly, atrial fibrillation, high pulmonary vascular resistance, and the results of the procedure in terms of residual gradient,final valve area, quality of commissural opening [4545. Messika-Zeitoun D, Blanc J, Iung B, Brochet E, Cormier B, Himbert D and Vahanian A. Impact of degree of commissural opening after percutaneous mitral commissurotomy on long-term outcome. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2:1-7. ], and presence of MR [4242. Kim MJ, Song JK, Song JM, Kang DH, Kim YH, Whan Lee C, Hong MK, Kim JJ, Park SW, and Park SJ. Long-term outcomes of significant mitral regurgitation after percutaneous mitral valvuloplasty. Circulation. 2006;114:2815-22. ]. The quality of the late results is generally considered to be independent of the technique used [4343. Kang DH, Park SW, Song JK, Kim HS, Hong MK, Kim JJ, and Park SJ. Long-term clinical and echocardiographic outcome of percutaneous mitral valvuloplasty: Randomized comparison of Inoue and double-balloon techniques. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:169-75. ].

The different predictive factors of late functional results can be combined using a scoring system enabling good functional results to be estimated in an individual patient according to baseline characteristics and the immediate results of PMC

Identification of predictors provides important information for patient selection and is relevant to follow-up: patients who have good immediate results but who are at high risk for further events must be carefully monitored to detect deterioration and allow timely intervention. Awareness of these predictors explains the discrepancies in follow-up results from reports that included patients with different characteristics: late results are clearly less satisfactory in North American and European series, where patients are older and frequently have severe valve deformities, than in studies from developing countries, where the patients studied have more favourable characteristics.

If the immediate results are unsatisfactory, midterm functional results are usually poor. The prognosis of patients with severe mitral regurgitation after surgical commissurotomy or PMC is usually poor, with a lack of symptom alleviation and secondary objective deterioration. Surgical treatment is usually necessary during the following months.

In cases of an insufficient initial opening, delayed surgery is usually performed when the extra-cardiac conditions allow it. Here, valve replacement is necessary in almost all cases because of the unfavourable valve anatomy that was responsible for the poor initial results.

If PMC is initially successful, survival rates are excellent, the need for secondary surgery is infrequent, and functional improvement occurs in most cases. In most cases the improvement in valve function is stable.

Restenosis rates are more difficult to assess than clinical outcome since they require standardised echocardiographic follow-up: this is difficult to organise, particularly in large series with a long follow-up. Even if there is no uniform definition, restenosis after PMC has generally been defined as a loss of more than 50% of the initial gain with a valve area of less than 1.5 cm2. After successful PMC, the incidence of restenosis is usually low, between 2% and 40% [4646. Wang A, Krasuski RA, Warner JJ, Pieper K, Kisslo KB, Bashore TM, and Harrison JK. Serial echocardiographic evaluation of restenosis after successful percutaneous mitral commissurotomy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:328-34. , 4747. Langerveld J, Thijs Plokker HW, Ernst SM, Kelder JC, Jaarsma W. Predictors of clinical events or restenosis during follow-up after percutaneous mitral balloon valvotomy. Eur Heart J. 1999;20:519-26. , 4848. Hernandez R, Bañuelos C, Alfonso F, Goicolea J, Fernández-Ortiz A, Escaned J, Azcona L, Almeria C, and Macaya C. Long-term clinical and echocardiographic follow-up after percutaneous mitral valvuloplasty with the Inoue balloon. Circulation. 1999;99:1580-6. ], at time intervals ranging from 3 to 10 years ( Figure 14 ). Age, mitral valve area after PMC, and anatomy are considered predictors of restenosis, but the small number of series reporting patients with restenosis and the limited duration of follow-up preclude any definite conclusion in this regard. The ability to perform repeat valvuloplasty in cases of recurrent mitral stenosis is one of the potentials of this non-surgical procedure. At the moment, despite the fact that repeat PMC represents 10% to 30% of the total number of balloon commissurotomies, only a few series are available on revalvuloplasty [4949. Bouleti C, Iung B, Himbert D, Brochet E, Messika-Zeitoun D, Détaint D, Garbarz E, Cormier B, Vahanian A. Long-term efficacy of percutaneous mitral commissurotomy for restenosis after previous mitral commissurotomy. Heart 2013;99:1336-41. , 5050. Bouleti C, Iung B, Himbert D, Brochet E, Messika-Zeitoun D, Détaint D, Garbarz E, Cormier B, Vahanian A.. Reinterventions after percutaneous mitral commissurotomy during long-term follow-up, up to 20 years: the role of repeat percutaneous mitral commissurotomy. Eur Heart J 2013;34:1923-30.

The most recent series on the results of PMC in patients with re-stenosis after a previous commissurotomy, 5151. Turgeman Y, Atar S, Suleiman K, Feldman A, Bloch L, Jabaren M, Rosenfeld T. Feasibility, safety, and morphologic predictors of outcome of repeat percutaneous balloon mitral commissurotomy. Am J Cardiol. 2005; 95:989-91.

The most recent series on the results of repeated percutaneous mitral commissurotomy, 5252. Pathan AZ, Mahdi NA, Leon MN, Lopez-Cuellar J, Simosa H, Block PC, Harrell L and Palacios IF. Is redo percutaneous mitral balloon valvuloplasty (PMV) indicated in patients with post-PMV mitral restenosis?. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34:49-54. ]: they report good immediate and midterm outcomes in patients with favourable characteristics.. Thus, re-PMC can be proposed in selected patients with favourable characteristics if the predominant mechanism is commissural re-fusion, and in cases with an initially successful PMC if restenosis occurs after several years. Although the results are less positive in patients presenting with worse characteristics, repeat valvuloplasty has a palliative role in patients who are at high risk for surgery [5252. Pathan AZ, Mahdi NA, Leon MN, Lopez-Cuellar J, Simosa H, Block PC, Harrell L and Palacios IF. Is redo percutaneous mitral balloon valvuloplasty (PMV) indicated in patients with post-PMV mitral restenosis?. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34:49-54. ].

Repeat valvular intervention may also be needed because of the progression of rheumatic heart disease on the aortic valve, either isolated or associated with mitral restenosis.

Follow-up studies using sequential TOE have shown that, despite numerous individual variations, the degree of mitral regurgitation, on the whole, remains stable or slightly decreases during follow-up. Atrial septal defects are likely to close later in most cases because of a reduced inter-atrial pressure gradient. The persistence of shunts is related to their magnitude (diameter of the defect >0.5 cm or QP [pulmonary blood flow]/QS [systemic blood flow] ratio >1.5) or to unsatisfactory relief of the valve obstruction. These defects very seldom require treatment on their own.

The low incidence of embolism during follow-up [5353. Chiang C-W, Lo S-K, Ko Y-S, Cheng N-J, Lin PJ, and Chang C-H. Predictors of systemic embolism in patients with mitral stenosis: A prospective study. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:885-9. ], the progressive decrease in intensity or disappearance of spontaneous echocardiographic contrast [5454. Cormier B, Vahanian A, Iung B, Porte JM, Dadez E, Lazarus A, Starkman C, and Acar J. Influence of percutaneous mitral commissurotomy on left atrial spontaneous contrast of mitral stenosis. Am J Cardiol. 1993;71:842-7. ], and the improved left atrial function [5555. Porte JM, Cormier B, Iung B, Dadez E, Starkman C, Nallet O, Michel PL, Acar J, and Vahanian A. Early assessment by transesophageal echocardiography of left atrial appendage function after percutaneous mitral commissurotomy. Am J Cardiol. 1996;77:72-6. ] after PMC suggest a beneficial effect of the procedure on left atrial blood stasis [5656. ZakiA, Salama M, El Masry M, Abou-Freikha M, Abou-Ammo D, Sweelum M, Mashhour E, and Elhendy A. Immediate effect of balloon valvuloplasty on hemostatic changes in mitral stenosis. Am J Cardiol. 2000;85:370-5. ], from which a lower risk of thromboembolism may be expected. [100100. Kang DH, Lee CH, Kim DH, et al. Early percutaneous mitral commissurotomy vs. conventional management in asymptomatic moderate mitral stenosis. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:1511-7. ] Finally, there is no direct evidence that PMC reduces the incidence of atrial fibrillation, even though it has a favourable influence on the predictors of atrial fibrillation (e.g., atrial size, degree of obstruction) [5757. Leon MN, Harrell LC, Simosa HF, Mahdi NA, Pathan A, Lopez-Cuellar J, Inglessis I, Moreno PR, and Palacios IF. Mitral balloon valvotomy for patients with mitral stenosis in atrial fibrillation: immediate and long-term results. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34:1145-52. , 5858. Kim JB, Ha JW, Kim JS, Shim WH, Kang SM, Ko YG, Choi D, Jang Y, Chung N, Cho SY, Kim SS. Comparison of long-term outcome after mitral valve replacement or repeated balloon mitral valvotomy in patients with restenosis after previous balloon valvotomy. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:1571-4. , 5959. Krasuski RA, Assar MD, Wang A, Kisslo KB, Pierce C, Harrison JK, and Bashore TM. Usefulness of percutaneous balloon mitral commissurotomy in preventing the development of atrial fibrillation in patients with mitral stenosis. Am J Cardiol. 2004;93:936-9. ]. Electric countershock cardioversion should be performed early after successful PMC if atrial fibrillation is of recent onset and in the absence of severe enlargement of the left atrium.

COMPARISON WITH SURGICAL COMMISSUROTOMY

The comparison of observational series may be biased by the confounding impact of differences in patient characteristics.

Randomised series analysing midterm results (3 to 7 years) following percutaneous or surgical commissurotomy consistently showed that PMC achieved results at least as good as surgical commissurotomy [6060. Turi ZG, Reyes VP, Raju BS, Raju AR, Kumar DN, Rajagopal P, Sathyanarayana PV, Rao DP, Srinath K, and Peters P. Percutaneous balloon versus surgical closed commissurotomy for mitral stenosis. A prospective, randomized trial. Circulation. 1991;83:1179-85. , 6161. Reyes VP, Raju BS, Wynne J, Stephenson LW, Raju R, Fromm BS, Rajagopal P, Mehta P, Singh S, Prasada Rao D, Satyanarayana PV, and Zoltan G. TuriPercutaneous balloon valvuloplasty compared with open surgical commissurotomy for mitral stenosis. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:961-7. , 6262. Ben Fahrat M, Ayari M, Maatouk F. Percutaneous balloon versus surgical closed and open mitral commissurotomy: Seven-year follow-up results of a randomized trial. Circulation. 1998;97:245-50. , 6363. Cardoso LF, Grinberg M, Pomerantzeff PM, Rati MA, Medeiros CC, Vieira ML, Virgen L, and Tarasoutchi F. Comparison of open commissurotomy and balloon valvuloplasty in mitral stenosis: A five-year follow-up. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2004;83:248-52. , 6464. Song JK, Kim MJ, Yun SC, Choo SJ, Song J-M, Song H, Kang D-H, Chung CH, Park DW, Lee SW, Kim Y-H, Lee CW, Hong M-K, Kim J-J, Lee JW, Park S-W, and Park S-J. Long-term outcomes of percutaneous mitral balloon valvuloplasty versus open cardiac surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;139:103-1. ]. In a series comparing the three techniques, the echocardiographic results of PMC were better than those of closed-heart commissurotomy and comparable to those of open-heart commissurotomy after a 7-year follow-up [6262. Ben Fahrat M, Ayari M, Maatouk F. Percutaneous balloon versus surgical closed and open mitral commissurotomy: Seven-year follow-up results of a randomized trial. Circulation. 1998;97:245-50. ]. However, randomised series included a majority of young patients with favourable mitral valve anatomy and their conclusions cannot be extended beyond this population. There are no randomised comparisons for older patients with more severe valve deformities, who represent the most frequent presentation of mitral stenosis in industrialised countries. A recent non-randomised comparison suggested that open-heart commissurotomy may provide better long-term functional results than PMC in patients with severe valve deformity, but the multiplicity of confounding factors limits the relevance of this finding [6464. Song JK, Kim MJ, Yun SC, Choo SJ, Song J-M, Song H, Kang D-H, Chung CH, Park DW, Lee SW, Kim Y-H, Lee CW, Hong M-K, Kim J-J, Lee JW, Park S-W, and Park S-J. Long-term outcomes of percutaneous mitral balloon valvuloplasty versus open cardiac surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;139:103-1. , 101101. Song JK, Kim MJ, Yun SC, Choo SJ, Song JM, Song H, Kang DH, Chung CH, Park DW, Lee SW, Kim YH, Lee CW, Hong MK, Kim JJ, Lee JW, Park SW, Park SJ. Long-term outcomes of percutaneous mitral balloon valvuloplasty versus open cardiac surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2010;139:103–110. ].

In the Euro Heart Survey, PMC accounted for 34% of all procedures performed to treat mitral stenosis, while surgical commissurotomy represented only 4% [66. Iung B, Baron G, Butchart EG, Delahaye F, Gohlke-Barwolf C, Levang OW, Tornos P, Vanoverschelde J-L, Vermeer F, Boersma E, Ravaud P and Vahanian A. A prospective survey of patients with valvular heart disease in Europe: The Euro Heart Survey on Valvular Heart Disease. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:1231-43. ]. Practically, the choice is now PMC or prosthetic valve replacement in most patients with mitral stenosis.

SELECTION OF PATIENTS

Patient evaluation

Besides diagnosis, clinical assessment of a patient with mitral stenosis aims in particular to analyse the consequences of mitral stenosis, i.e., symptom severity, a history of embolism, and cardiac rhythm.

Transthoracic echocardiography is the most important investigation for the choice of treatment strategy. Assessment of the severity of mitral stenosis is based on planimetry using the parasternal short-axis view, which is the reference measurement but requires expertise and may be difficult in patients with poor acoustic window or severe valve deformity [6565. Baumgartner H, Hung J, Bermejo J, Chambers JB, Evangelista A, Griffin BP, Iung B, Otto CM, Pellikka PA, and Quiñones M; EAE/ASE. Echocardiographic assessment of valve stenosis: EAE/ASE recommendations for clinical practice. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2009;10:1-25. ]. Real-time three-dimensional echocardiography is helpful for improving the accuracy of planimetry [6666. Wunderlich NC, Beigel R, Siegel RJ. Management of mitral stenosis using 2D and 3D echo-Doppler imaging. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2013;6:1191-205. , 6767. Min SY, Song JM, Kim YJ, Park HK, Seo MO, Lee MS, Kim DH, Kang DH, Song JK. . Discrepancy between mitral valve areas measured by two-dimensional planimetry and three-dimensional transoesophageal echocardiography in patients with mitral stenosis. Heart 2013;99:253-8. , 6868. Messika-Zeitoun D, Meizels A, Cachier A, Scheuble A, Fondard O, Brochet E, Cormier B, Iung B, and Vahanian A. Echocardiographic evaluation of the mitral valve area before and after percutaneous mitral commissurotomy: the pressure half-time method revisited. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18:140914. ]. Doppler pressure half-time is less reliable because it also depends on confounding factors, in particular chamber compliance and associated aortic regurgitation. Discrepancies with planimetry are more marked in patients aged over 60, in those in atrial fibrillation, and immediately after PMC. Mitral gradient is easy to measure by Doppler but is also highly dependent on haemodynamic conditions, in particular cardiac output. In most cases, the conjunction of planimetry, pressure half-time and mean gradient enables the severity of mitral stenosis to be defined. In the rare cases where these measurements cannot be conclusive, mitral valve area can be assessed using continuity equation or flow convergence [6969. Messika-Zeitoun D, Fung Yiu S, Cormier B, Iung B, Scott C, Vahanian A, Tajik AJ, and Enriquez-Sarano M. Sequential assessment of mitral valve area during diastole using colour M-mode flow convergence analysis: new insights into mitral stenosis physiology. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:1244-53. ]. Systolic pulmonary artery pressure is more a marker of the consequences of mitral stenosis than of its severity.

PMC is only considered in patients with moderate to severe mitral stenosis. The progression from moderate to severe mitral stenosis is slow and highly variable from one patient to another. Therefore, the risk of an interventional procedure, even if low, is not justified at this stage to prevent the evolution towards severe stenosis. In practice, intervention is only considered in patients with a mitral valve area <1.5 cm2, this threshold being interpreted according to patient body size, mitral gradient, and clinical tolerance

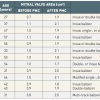

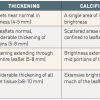

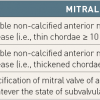

The other main application of echocardiography is the evaluation of valve anatomy. The suitability for PMC depends on different anatomic features of the mitral valve apparatus: leaflet thickening, leaflet pliability, degree of involvement of the subvalvular apparatus (chordal thickening and all shortening), and presence of calcification. These features are usually combined in a scoring system. The most widely used is the Wilkins score, which ranks each component between 1 and 4 and adds them together to obtain a score between 4 and 16 ( Table 4 ) [7070. Nunes MC, Tan TC, Elmariah S, do Lago R, Margey R, Cruz-Gonzalez I, Zheng H, Handschumacher MD, Inglessis I, Palacios IF, Weyman AE, Hung J. . The echo score revisited: Impact of incorporating commissural morphology and leaflet displacement to the prediction of outcome for patients undergoing percutaneous mitral valvuloplasty. Circulation. 2014;129:886-95. , 7171. Wilkins GT, Weyman AE, Abascal VM, Block PC, Palacios IF. Percutaneous balloon dilatation of the mitral valve: an analysis of echocardiographic variables related to outcome and the mechanism of dilatation. Br Heart J. 1988;60:299-308. ]. Another approach is Cormier’s score which consists in an overall approach to the mitral apparatus defining three classes ( Table 5 ) [2222. Iung B, Cormier B, Ducimetiere P, Porte JM, Nallet O, Michel PL, Acar J and Vahanian A. Immediate results of percutaneous mitral commissurotomy. A predictive model on a series of 1514 patients. Circulation. 1996; 94:2124-30. ]. The three classes of Cormier’s score correspond to the most appropriate surgical alternative: class 1 corresponds to ideal indications for commissurotomy, class 2 to intermediate indications for commissurotomy, and class 3 to indications for prosthetic valve replacement. In fact, none of the scores available today has been shown to be superior to the others, and all echocardiographic classifications have the same limitations: (1) reproducibility is difficult, because the scores are only semi-quantitative; (2) lesions may be underestimated, especially with regard to the assessment of subvalvular disease; and (3) the use of scores describing the degree of overall valve deformity may not identify localised changes in specific portions of the valve apparatus (leaflets, and especially commissures), which may increase the risk of severe mitral regurgitation. Therefore, we can only recommend the use of the system with which one is most familiar and at ease.

More detailed scores have been described in order to refine the prediction of the immediate results of PMC [7070. Nunes MC, Tan TC, Elmariah S, do Lago R, Margey R, Cruz-Gonzalez I, Zheng H, Handschumacher MD, Inglessis I, Palacios IF, Weyman AE, Hung J. . The echo score revisited: Impact of incorporating commissural morphology and leaflet displacement to the prediction of outcome for patients undergoing percutaneous mitral valvuloplasty. Circulation. 2014;129:886-95. , 7272. Cannan CR, Nishimura RA, Reeder GS, Ilstrup DR, Larson DR, Holmes DR, and Tajik J. Echocardiographic assessment of commissural calcium: a simple predictor of outcome after percutaneous mitral balloon valvotomy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;29:175-80. , 7373. Fatkin D, Roy P, Morgan JJ, Feneley MP. Percutaneous balloon mitral valvotomy with the Inoue single-balloon catheter: commissural morphology as a determinant of outcome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;21:390-7. , 7474. Padial LR Freitas N, Sagie A, Newell JB, Weyman AE, Levine RA, and Palacios IF. Echocardiography can predict which patients will develop severe mitral regurgitation after percutaneous mitral valvulotomy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;27:1225-31. ]. Some of these include a detailed assessment of the impairment of commissural areas, which is likely to influence the results of PMC. However, these scoring systems have been tested only in small populations, and no large series have demonstrated a better ability to predict the results of PMC. In addition, the complexity of more detailed scores raises concerns regarding their current use and their reproducibility.

Echocardiography is also useful for assessing combined aortic or tricuspid valve disease and to quantify left atrial enlargement. Left ventricular function is generally preserved but may be altered in rare cases.

Transoesophageal echocardiography may be used to assess valve anatomy in patients with poor acoustic window. Its main indication is to rule out the presence of left atrial thrombosis before performing PMC. It should be performed a few days before all PMCs. In addition, the assessment of left atrial spontaneous contrast contributes to risk stratification for thromboembolism.

Cardiac catheterisation is no longer considered as the reference method for assessing the severity of mitral stenosis. Right-heart catheterisation may be useful in patients with severe pulmonary hypertension, in particular to assess pulmonary vascular resistance.

Contraindications for percutaneous mitral commissurotomy or surgery

It is mandatory to eliminate contraindications to PMC before the procedure. On the other hand, the presence of contraindications for surgery is an incentive to perform PMC.

Contraindications for PMC

Contraindications to transseptal catheterisation include suspected left atrial thrombosis, severe haemorrhagic disorder, and severe cardiothoracic deformity.

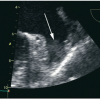

Left atrial thrombus is the main contraindication for PMC ( Figure 15 ), although some small series have suggested that it could be attempted under transoesophageal echocardiographic guidance when the thrombus is located in the left atrial appendage [7575. Shaw TRD, Northridge DB, Sutaria N. Mitral balloon valvotomy and left atrial thrombus. Heart. 2005;91: 1088-9. ]. Our opinion, however, is that there is not enough evidence for the safety of this approach, which may only be considered in inoperable or very high risk patients. Left atrial thrombus is not a definite contraindication since it can disappear after optimisation of anticoagulant therapy. Thus, PMC can be reconsidered after 2 to 6 months if a new transoesophageal echocardiography shows the disappearance of the thrombus [7676. Silaruks S, Thinkhamrop B, Kiatchoosakun S, Wongvipaporn C, and Tatsanavivat P. Resolution of left atrial thrombus after 6 months of anticoagulation in candidates for percutaneous transvenous mitral commissurotomy. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:101-5. ]. This strategy is particularly indicated if the patient is clinically stable, if valve anatomy is suitable for PMC, and if prior anticoagulant therapy was suboptimal.

More than mild mitral regurgitation generally contraindicates PMC. PMC can, however, be considered in selected patients with MR 2+ if the risk of surgery is high, such as in pregnant patients, provided valve anatomy is favourable. Severe regurgitation is of course a definite contraindication.

Bicommissural mitral valve calcification is a contraindication for PMC. The presence of unilateral calcification is not a predictor of poor long-term results and does not represent by itself a contraindication for PMC [102102. Dreyfus J, Cimadevilla C, Nguyen V, Brochet E, Lepage L, Himbert D, Iung B, Vahanian A, Messika-Zeitoun D.. Feasibility of percutaneous mitral commissurotomy in patients with commissural mitral valve calcification. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:1617-23. ]. In patients who have previously undergone balloon or surgical commissurotomy, the persistence of complete opening of one or both commissures indicates that restenosis is due to valve rigidity and is an indication for mitral valve replacement

Other severe valvular disease or coronary heart disease requiring surgery contraindicates PMC and should lead to the consideration of combined surgical treatment. In patients with severe degenerative MS combined with severe aortic valve disease, where transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) is considered as the preferred option on the aortic valve very preliminary experience suggested that a subsequent transcatheter mitral valve implantation is feasible if the symptoms persist after TAVI [103103. Vahanian A, Himbert D, Brochet E. Multiple valve disease - assessment, strategy and intervention. EuroIntervention. 2015;11(W):W14-W16 ].

The only exception is severe tricuspid regurgitation which does not contraindicate PMC, provided it is of functional origin and not associated with a severe enlargement of right heart cavities and atrial fibrillation [7777. Song H, Kang DH, Kim JH, Park K-M, Song J-M Choi K-J, Hong M-K, Chung CH, Song J-K, Lee J-W, Park S-W, and Park S-J. Percutaneous mitral valvuloplasty versus surgical treatment in mitral stenosis with severe tricuspid regurgitation. Circulation. 2007;116:I246-50. ].

Contraindications to percutaneous mitral commissurotomy

- Mitral valve area >1.5 cm²

- Left atrial thrombus

- More than mild mitral regurgitation

- Severe or bicommissural calcification

- Absence of commissural fusion

- Severe concomitant aortic valve disease, or severe combined tricuspid stenosis and regurgitation

- Concomitant coronary artery disease requiring bypass surgery

On the other hand, the combination of severe mitral stenosis with moderate aortic valvular disease favours the use of PMC in order to postpone multiple valve surgery.

Contraindications to surgery

Definite contraindications for surgery are rare and should be assessed by a “heart team” consisting of cardiologists and cardiac surgeons using validated scores [7878. Roques F, Nashef SA, Michel P, Gauducheau E, de Vincentiis C, Baudet E, Cortina J, David M, Faichney A, Gabrielle F, Gams E, Harjula A, Jones MT, Pintor PP, Salamon R, Thulin L. Risk factors and outcome in European cardiac surgery: analysis of the EuroSCORE multinational database of 19 030 patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1999;15:816-23. , 7979. Edwards FH, Peterson ED, Coombs LP, DeLong ER, Jamieson WR, Shroyer ALW, Grover FL. Prediction of operative mortality after valve replacement surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:885-92. ].

PMC may be favoured over surgery in patients with high expected operative risk, even in the presence of unfavourable characteristics.

TREATMENT STRATEGY

The selection of an individual candidate for PMC must be based on both clinical and anatomic variables, bearing in mind that anatomy is a simple, practical way to select patients for PMC even though it is not the sole criterion ( Figure 16 and Table 6 ).

Symptomatic patients

In patients with severe mitral stenosis, the presence of symptoms is a class I indication for intervention according to guidelines [8080. ESC /EACTS 2012 GUIDELINES Vahanian A, Alfieri O, Andreotti F, Antunes MJ, Barón-Esquivias G, Baumgartner H, Borger MA, Carrel TP, De Bonis M, Evangelista A, Falk V, Iung B, Lancellotti P, Pierard L, Price S, Schäfers HJ, Schuler G, Stepinska J, Swedberg K, Takkenberg J, Von Oppell UO, Windecker S, Zamorano JL, Zembala M. Joint Task Force on the Management of Valvular Heart Disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC); European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS), Guidelines on the management of valvular heart disease (version 2012). Eur Heart J. 2012 ;33:2451-96.

The ESC/EACTS GUIDELINES ON VALVULAR HEART DISEASE, 8181. Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Erwin JP 3rd, Guyton RA, O'Gara PT, Ruiz CE, Skubas NJ, Sorajja P, Sundt TM 3rd, Thomas JD. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines.J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014 63:e57-185.

THE ACC/AHA Guidelines on valvular heart disease]. In these patients, the problem is the choice of the most appropriate technique: this depends on the suitability for PMC and contraindications or risks inherent to PMC or surgery. Favourable patient characteristics for PMC have been defined according to the identification of predictive factors of good immediate and late results.