Summary

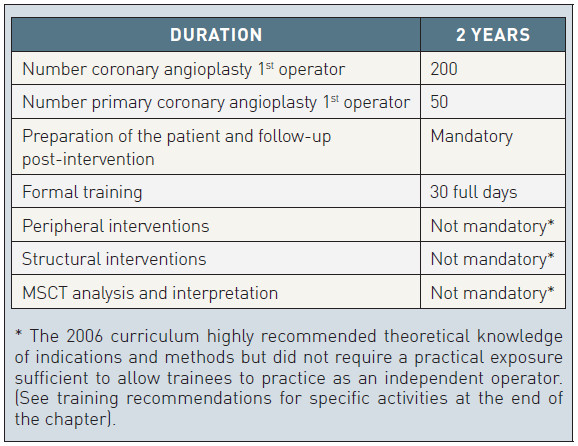

Interventional cardiology training programs are conducted within or after the general cardiology training in most European countries but, unlike in the United States, they do not attract legal recognition. To stimulate the development of official homogeneous subspecialty training programs across Europe, the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI) has developed a Curriculum and Syllabus and launched a web based educational platform. The two year program recommended requires 200 coronary angioplasty procedures as first operator with at least 50 primary angioplasties for ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Specific training in structural or peripheral interventions or in the reconstruction and interpretation of multidetector computed tomography was not yet requested in this 12 years old document, now under review. The absence of binding specifications for interventional training is mirrored by the absence of a revalidation program with no specific indications for continuous medical education in interventional cardiology. In practice, however, subspecialty training in interventional cardiology is provided at high level in most European countries, adopting or modifying the EAPCI Curriculum and running the training during and around the last year of official Fellowship. EAPCI is a large provider of interventional cardiology training, offering specific fellows’ courses, and education. Its annual congress EuroPCR is the largest interventional course in the world.

History and current status of interventional training

FROM GRUENTZIG TO EuroPCR

In the past, a diploma for attendance at the Gruentzig courses in Zurich was a prerequisite for purchasing angioplasty balloons and guiding catheters from Schneider, the only company manufacturing this material in the 1970’s. Many things have changed since the time of those early pioneers, but Europe has maintained its worldwide lead in the organisation of educational courses. The mythical live demonstrations of Gruentzig in Zurich which created a core group of early adopters have been followed by other successful events such as the Meier course in Geneva, the Reifart course in Frankfurt, the Colombo/Grube course in Rome and Milan, the Serruys course in Rotterdam and the Marco course in Toulouse and Paris. From these last two events stemmed the EuroPCR course which became, in 2007, the official annual congress of the EAPCI, the largest educational event in interventional cardiology worldwide. The programme committee for this event, now composed of more than 30 experts including 11 presidents of national European interventional societies, tries hard in its long series of preparatory meetings to achieve a fair balance between information, with the selection of new trial results and abstracts, and education, in the format of symposia, Live and Live-in-a-Box cases, “PCR got talent” sessions.

In 2005 EAPCI established a 2-day fellows course initially held in London and Krakow but followed, with appropriate modifications and often in the local language, in many European countries under the auspices of the national interventional societies. Since 2014 and under the direct supervision of the EAPCI Young group the course has moved to the Heart House in Sophia Antipolis. From 2017 the EAPCI Fellows Course will be linked to the EuroPCR congress in Paris, which is EAPCI´s main congress. Training fellowships for young interventionists to travel abroad are offered yearly by EAPCI, allowing candidates the opportunity to move to different centres and countries, thus promoting a more homogeneous training process throughout Europe [11. https://www.escardio.org/Education/Career-Development/Grants-and-fellowships/EAPCI-interventional-cardiology-training-and-research-grants

].

INTERVENTIONAL CARDIOLOGY TRAINING IN EUROPE

The impetus behind many of these initiatives is the need to fill the gap caused by the lack of a formal programme of interventional cardiology training delivered by universities and teaching hospitals. In most European countries, the cardiology training Fellowship, now shortened to 4 years throughout Europe, consists of a period of training in internal medicine followed by specific training in cardiology, covering the different invasive and non-invasive fields. A formal programme of interventional training is in place in very few countries and is hardly ever enforced by appropriate legislation. The practical consequence of this absence of a formal training programme for interventional cardiologists is that all cardiologists (and also many other medical specialists such as radiologists, cardiac surgeons and vascular surgeons) are legally entitled to perform percutaneous interventional procedures after successful completion of training in their main specialty without any specific knowledge and experience in the interventional field. Radiologists, vascular and cardiac surgeons can make the opposite claim when cardiologists embark in the interpretation of non-invasive diagnostic tests, such as MSCT, or perform peripheral interventions or transcatheter valve procedures, sometimes using mini-invasive but still surgical approaches. Although the training of specialists in interventional cardiology is often not formally regulated, the appointment of cardiologists who are expected to carry out angioplasties and other interventional procedures is, in practice, restricted by the selection process with specific requirements to be admitted to the final interview. France was the first European country to move to a structured programme with formal courses and a final exam, swiftly followed by The Netherlands, Denmark, Poland and others.

INTERVENTIONAL CARDIOLOGY TRAINING IN THE US, LATIN AMERICA AND ASIA

In the US the core training programme in cardiology consists of 3 years of internal medicine training followed by 3 years of cardiology training. Until 2000 training was expected to cover all aspects of non-invasive and invasive cardiology.

The consequence was a rapid growth in the number of interventional specialists with a dangerous trend towards the creation of a vast number of low volume operators with inadequate training. Several publications showed a clear relationship between lower operator volumes and increased rates of emergency coronary artery bypass surgery in both the pre-stent and stent eras [22. Seymour N, Gallagher AG, Roman SA, O’Brien MK, Bansal VK, Andersen DK, Satava RM. Virtual reality training improves operating room performance: results of a randomized, double blinded study. Ann Surg. 2002; 236:458-64. , 33. Patel AD, Gallagher AG, Nicholson WJ, Cates CU. Learning curves and reliability measures for virtual reality simulator in the performance assessment of carotid angiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:1796-802. ].

In 1999 The Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions and The American College of Cardiology promoted, with the support and agreement of the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM), the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS), and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), a new dedicated subspecialty programme for interventional cardiology.

To be eligible, a candidate had to hold a valid existing board certification in internal medicine and cardiovascular diseases. The candidate then applied through either the practice pathway (“grandfathers” with no formal interventional fellowship) or the training pathway (with formal interventional fellowship) meeting specified procedural requirements. The practice pathway ended with the 2003 examination. Thereafter, all applicants had to qualify via the training pathway with graduation from an ACGME approved interventional fellowship experience after having passed a specific examination. The interventional cardiology examination is a timed multiple-choice format examination taken over 2 days. At present, the question content is divided as follows: case selection 25%; procedural techniques 25%; imaging 15%; pharmacology 15%; basic science 15%; miscellaneous 5% [44. Di Mario C, Babb J. Interventional cardiology training. From Di Mario C, Dangas GD, Barlis P (eds) Interventional cardiology: Principles and Practice, Wiley-Blackwell 2011, p.3-9 ]. No other country can claim such a stringent regulation in interventional training, which arguably represented a turning point in the US and ensured a rapid improvement in the quality of the operators. In Latin America, SOLACI has promoted a one year common pattern of training with similarities to the US training programme but lacking the legal certification in most individual countries. In Asia also, subspecialty training is not legally recognised but the pyramidal model applied in most hospitals is expected to ensure appropriate supervision and continuous growth in interventional skills. In Europe we often idealise the “Japanese” model of training with its very slow progression from vascular access to diagnostic procedures and preparation of the lesion for final completion, which is assigned only to senior operators. In reality, Japanese operators are probably the best worldwide and those who have followed a course in Japan or a lecture from one of their CTO experts know how much attention is given to minute technical details such as wire shaping, material selection and handling.

CURRENT INITIATIVES OF THE EUROPEAN SOCIETY OF CARDIOLOGY AND ITS ASSOCIATIONS ON SUBSPECIALTY TRAINING

The Core Curriculum in Cardiology was published by the Education Committee of the European Society of Cardiology [55. https://www.escardio.org/Sub-specialty-communities/European-Association-of-Percutaneous-Cardiovascular-Interventions-(EAPCI)/Education#EAPCI%20Core%20Syllabus

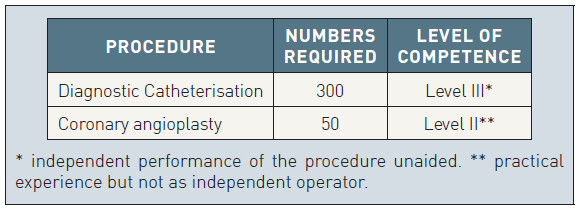

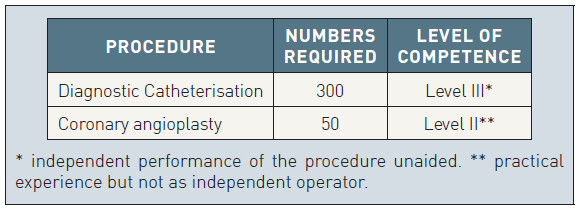

] and contains an ideal pattern of training for the general cardiologist approved by all the national society members of the ESC. In The Core Curriculum, a minimum of 300 catheterisations as first operator are required. For diagnostic catheterisation (right and left, with coronary angiography and left ventriculography) the level required (Level III) implies that the trainee is able to “independently perform the procedure unaided” at the end of his/her training. Percutaneous interventions is listed among the required techniques but a lower number of 50 procedures is specified and the competence Level required is Class II which indicates “practical experience but not as independent operator”. The Core Curriculum, promoted and implemented by the European Society of Cardiology and recently updated, implicitly recognises that percutaneous interventions are part of a different subspecialty training. In 2007 the European Society of Cardiology and the European Union of Medical Specialists (UEMS) nominated a task force to identify the areas in need of specific additional training at the end of, or integrated into, cardiology training. That committee has endorsed the concept that the practice of activities such as interventional cardiology, electrophysiology and pacing, cardiovascular imaging and heart failure treatment require a specific and additional training and they have set the general rules for regulating its organisation that requires devolving to each individual professional association the development of the specific educational content of the programmes [66. Lopez-Sendon J, Mills P, Weber H, Michels R, Di Mario C, Filippatos G, Heras M, Fox K, Merino J, Pennell DJ, Sochor H, Ortoli J on behalf of the Coordination Task Force on Sub-speciality Accreditation of the European Board for the Speciality of Cardiology. Recommendations on sub-speciality accreditation in Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:2163-71.

This article reports the requirement for the various subspecialties within the European Society of Cardiology to start a training program, from the definition of a curriculum and syllabus to the modalities to run a final exam].

Invasive and interventional requirements for the general training of cardiologists (ESC Curriculum 2009)

The European curriculum and syllabus of interventional cardiology training

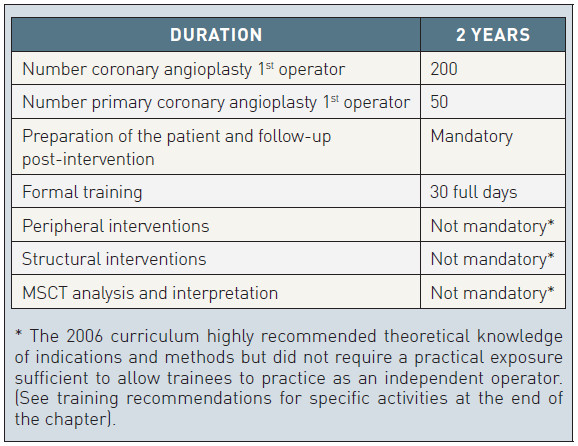

After several meetings between members of the ESC Working Group (WG) of Interventional Cardiology and the chairmen of the national interventional societies, a committee was appointed to finalise a curriculum and syllabus for interventional cardiology training in Europe. The final document was published in EuroIntervention in 2006 [77. Di Mario C, Di Sciascio G, Dubois-Randé LG, Michels R, Mills P. Curriculum and syllabus for interventional cardiology subspecialty training in Europe. EuroIntervention. 2006;2:31-6.

This first attempt to design a curriculum of interventional cardiology training and to identify its topics in a complementary syllabus is due to undergo an update targeting new needs in peripheral and structural interventions and the rise of non-invasive coronary angiography with MSCT]. The purpose of the curriculum was to provide a template for a homogeneous educational process for specialists in interventional cardiology in Europe. The curriculum instructs a two year programme divided into four semesters, with a stepwise approach to the direct engagement of the trainee who is expected to start dealing with the preparation of the patient for the intervention, including diagnostic angiography, and then assist (as second operator) the supervisor or other experienced interventionists performing the angioplasty procedure. It is recommended that the trainee starts working as a primary operator for simple angioplasties under close supervision and assists in the most complex angioplasty procedures (bifurcations, thrombus containing lesions, chronic occlusions, diffuse disease, severe calcifications, etc.) until he/she reaches a level of confidence allowing him/her to work as a primary and independent operator in both simple and complex coronary interventional procedures. Apprenticeship learning was defined as the mainstay of the training process in interventional cardiology. Candidates are required to be involved in procedure planning, assessment of indications and contraindications, specific establishment of the individual patient risks based on clinical and angiographic characteristics. A parallel formal learning programme is also required ensuring that the candidate achieves sufficient knowledge of all of the subjects included in the syllabus. Trainees are required to attend at least 30 full days (240 hours) in 2 years of specific interventional training sessions locally (study days and post graduate courses), nationally (for instance the annual congress of the national interventional society, often hosting dedicated courses for fellows) and internationally (for instance EuroPCR, the annual official congress of EAPCI). Distance learning through journals, textbooks and the Internet is also encouraged, facilitated by the abundant free educational material available in the ESC, EAPCI and PCRonline websites together with free access to all the articles of EuroIntervention, the official journal of EAPCI [88. https://www.escardio.org/Journals/ESC-Journal-Family/EuroIntervention

]. In the curriculum it is indicated that all trainees must be exposed through the training programme to a basic knowledge of the methods of research and interpretation of trial results in interventional cardiology.

Minimum requirements for interventional training according to the EAPCI curriculum

From principle to practice: The European web platform for interventional cardiology training

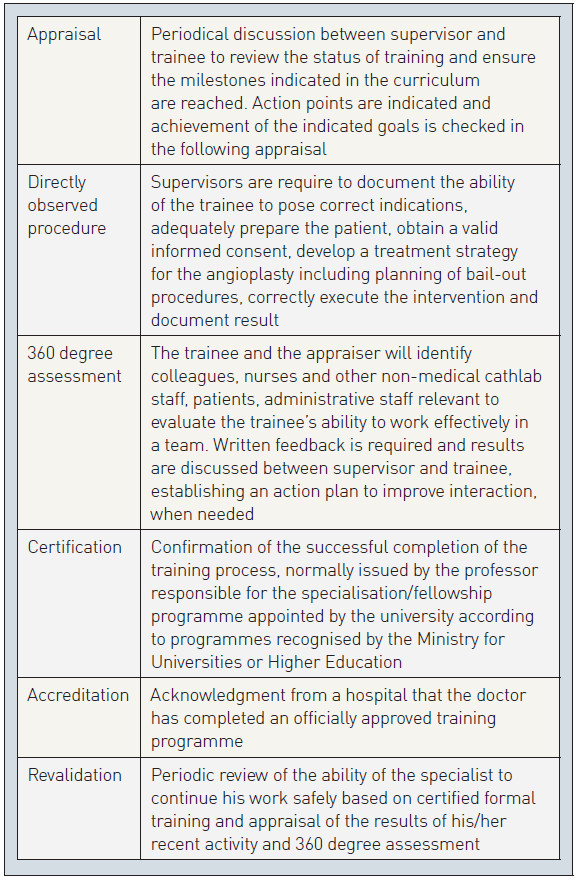

It is a formidable challenge to promote a homogeneous high standard of training when no central European government is willing to endorse it with legal recognition. The solution adopted by the ESC and its sister subspecialty organisations EIA, EHRA, ACCA and EAPCI is the development of web-based platforms dedicated to subspecialty training, with the scientific and educational content determined by the individual associations within a general scheme valid for all the subspecialties. The three cornerstones of the training process are knowledge, professional skills and professionalism. The most knowledgeable cardiologist with a complete background spanning from pathophysiology of coronary artery disease to the results of the most recent trials will be unable to work safely if he/she has not achieved sufficient practical experience in a variety of procedures, assisted and coached by qualified supervisors. Similarly, a physician combining good theoretical knowledge and hands-on experience can still be inefficient and dangerous if he/she does not show respect and human compassion towards patients in his/her practice and does not have the ability to select and motivate his/her team. Training in interventional cardiology must address these three complementary, essential aspects of the education process and must develop reliable methods of assessment to certify the progress made so as to indicate the additional steps required to become an independent professional.

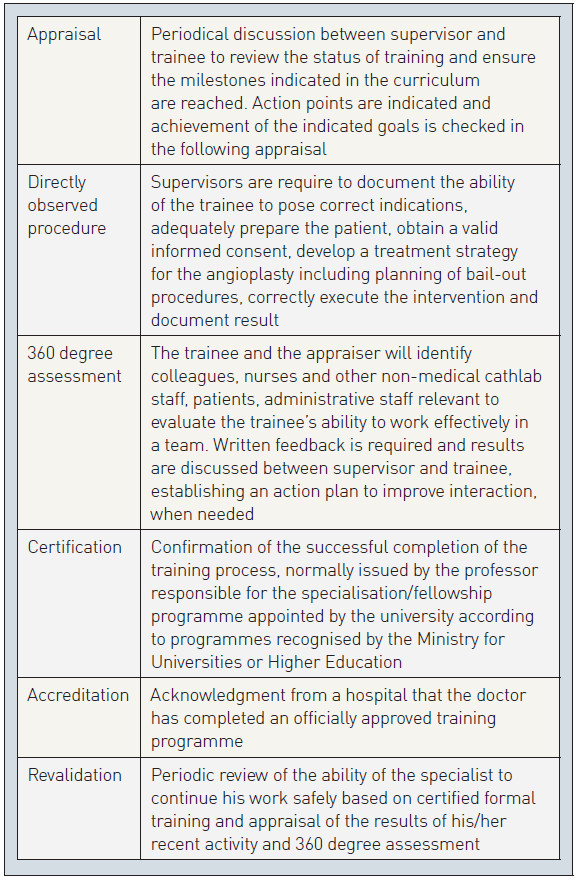

The platform had its first release in 2016, offering the trainee the possibility to document attendance at accredited formal training courses and to record their catheter lab based procedures [99. https://www.escardio.org/Sub-specialty-communities/European-Association-of-Percutaneous-Cardiovascular-Interventions-(EAPCI)/Education/The-ESC-eLearning-platform

]. The website asks for mandatory reports of directly observed procedures, periodical appraisals from the programme director and a 360 degree assessment, involving not only medical colleagues but also nurses, radiographers, technicians and patients. The final judgement should report on the trainee’s ability to interact with cath lab staff and colleagues, his/her attention to minimising patient risk by maintaining a good balance between a disposition to discuss complex procedures with more expert colleagues and the ability to make independent appropriate choices and cope with emergency situations. Currently no final comprehensive examination is envisaged for the end of the training. Multiple choice questions (MCQs), however, are embedded into the section testing theoretical knowledge. After having read the educational content of its various parts, regularly updated, the candidate is prompted to complete the training answering appropriate questions.

Suitable training centres are identified with the support of the national interventional societies. They are asked to fulfil certain technical and staffing requirements. These include having an independent interventional cardiology unit allowing the trainee to follow the patient from the beginning to the completion of the interventional treatment and having a volume of coronary angioplasties per year, including acute coronary syndromes and primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. At least two certified supervisors must be available, both with an experience of at least 1,000 coronary interventions and more than five years’ experience mainly dedicated to interventional cardiology.

Essential terminology pertinent to medical training and revalidation

Continuous medical education: Specificity of interventional cardiology training

In a dynamic subspecialty such as interventional cardiology, with new material and techniques continuously being introduced, CME appears indispensable to maintain acceptable quality standards. Many European countries have established quality standards for revalidation in the various specialties, with the need to enter all the accredited courses followed and ensure they fit into the CME requirements of the specialist involved [1010. http://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/education/professional -development ]. Obviously, since interventional cardiology is not officially considered a subspecialty, no specific CME requirements have been indicated in this field. A minimal number of 75 PCI procedures per operator per annum is recommended by the national societies in most European countries and this can be often tracked in dedicated databases open to the public reporting individual results. In the USA, however, besides evidence that this minimum number of procedures has been effectively performed, a formal revalidation process is required every ten years with interventionists required to sit a similar ABIM MCQ-based test to the test designed for new fellows. This additional burden on the shoulders of busy interventionalists, coming at a cost, has raised criticism. The ability of such tests to screen the presence of the minimal requirements for a safe practice has been questioned [1010. http://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/education/professional -development ]. This healthy scepticism has to be considered to avoid transforming a process monitoring the ability of an interventionalist to perform into another bureaucratic process

Simulators for interventional cardiology training

Medical errors have been the fundamental reason for the creation of virtual reality training instruments for medical interventions. Error reduction in healthcare is a major task and has high priority for patient safety and to reduce the increasing costs of litigation [1111. Sharpe VA, Faden AL. Medical Harm. Historical, conceptual and ethical dimensions of iatrogenic illness. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1998. , 1212. Spath PL. Error reduction in health care. A system approach to improving patient safety. Chicago: Health forum, inc, 2000. ]. For centuries the traditional training model in medicine has been the direct exposure to procedures conducted on patients under appropriate monitoring by the trainee’s mentor. All interventional procedures are associated with a learning curve for the operator. During this learning curve it is generally accepted that there is a higher number of complications and a lower quality of performance than in procedures performed by experts. It is no longer acceptable to teach future operators using this apprenticeship model and the principle of competency-based training must prevail over volume-based training [1313. Aggarwal R, Darzi A. Technical-skills training in the 21st century. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2695-96. ]. Simulators have been a part of the aviation training curriculum for decades and this methodology has now been accepted in medical education to reduce errors, costs and to increase safety for the patient and protect the trainee and his mentor. Advanced simulators for different surgical procedures have been on the market for more than two decades and the training effect has been demonstrated in several RCTs [1414. Grantcharov TP, Kristiansen VB, Bendix J, Bardram L, Rosenberg J, Funch-Jensen P. Randomized clinical trial of virtual reality simulation for laparoscopic skills training. Br J Surg. 2004;91:146-50.

Seminal paper on the use of simulators for medical training providing documented evidence that simulators can facilitate operators’ training in laparoscopic surgery with measurable outcome data such as reduction of procedural duration and improvement of success, 1515. Rosenfield K, Babb JD, Cates CU, Cowley MJ, Feldman T, Gallagher A, Gray W, Green R, Jaff MR, Kent KC, Ouriel K, Roubin GS, Weiner BH, White CJ. Clinical competence statement on carotid stenting: training and credentialing for carotid stenting –multispecialty consensus recommendations: a report of the SCAI/ SVMB/SVS Writing Committee to develop a clinical competence statement on carotid interventions. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:165-74.

An official statement on competency in carotid stenting developed in cooperation by the main US societies of vascular surgery, interventional radiology and cardiology offering a model to launch a similar initiative in Europe]. Simulators for cardiac interventional procedures have been on the market for a decade but unfortunately the improvement obtained training on a simulator has not been clearly demonstrated by head-to-head comparisons with the traditional apprenticeship model. Many attempts to validate the training effect in different angiographic simulators have been performed and some studies suggested a shorter and more consistent path to training completion [1616. Di Mario, C. Interventional cardiologists: a new breed. EuroIntervention. 2009;5:535-37. ]. Only a few attempts have been made to demonstrate the transfer effect in peripheral interventions [1717. Mark DB, Berman DS, Budoff MJ, Carr JJ, Gerber TC, Hecht HS, Hlatky MA, Hodgson JM, Lauer MS, Miller JM, Morin RL, Mukherjee D, Poon M, Rubin GD, Schwartz RS; American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Expert Consensus Documents. ACCF/ACR/AHA/NASCI/SAIP/SCAI/SCCT 2010 expert consensus document on coronary computed tomographic angiography: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Expert Consensus Documents. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;76 :E1-42.

A cooperative document of Cardiology and Radiology US Societies to define competency in non-invasive coronary imaging with MSCT] but no consistent attempts in coronary interventions. The high cost of simulators and the lack of compelling proofs of improvement may explain the slow pace of adoption of these expensive tools, belittled by conservative trainers as expensive video games. A wider adoption has followed the increased popularity of structural interventions. Each Company has developed a training process that includes working on a mannequin generating an angiographic feed-back to the manoeuvres performed on the valve delivery system or other interventional devices. Modern simulators are suitable to run modules to teach not only coronary angiography and simple PCI but also modules to train CRT implantation, trans-septal puncture, pulmonary venous isolation, bifurcation stenting, CTO, LAA appendage closure and TAVI procedures. ESC and several national cardiology societies recognise the potential of this training method and now recommend the use of simulators in their curriculum for cardiology trainees. With a validated tool we can optimise and assess the training and define strict entry levels of adequate proficiency level before allowing the trainee to perform the intervention on a patient.

Training in peripheral interventions, treatment of structural heart diseases, non-invasive angiography with multidetector computed tomography and other invasive imaging techniques (intravascular ultrasound, optical coherence tomography)

The European Curriculum does not include any of the above topics as mandatory components of its training. This implies three things:

- the Curriculum is focused on the basics of interventional training with special emphasis placed on the most successful and lifesaving applications of interventional cardiology in acute coronary syndromes;

- the practice in the various European countries is very different with peripheral interventions and MSCT accepted as “cardiovascular” applications practiced by cardiologists in some member countries and strictly limited to radiologists in others;

- the Curriculum was developed in 2004-05, long before the ‘’valve’’ revolution.

TRANSCATHETER PERIPHERAL INTERVENTIONS

The main challenge facing interventional cardiology is the definition for each individual procedure (carotid, renal, lower limb stenting, abdominal aneurysm exclusion) of a consistent pattern of training accepted by the other specialists potentially involved in these procedures. Some successful examples from the US of agreement among neuroradiologists, vascular surgeons and interventional cardiologists are certainly a positive stimulus for similar achievements in Europe [1717. Mark DB, Berman DS, Budoff MJ, Carr JJ, Gerber TC, Hecht HS, Hlatky MA, Hodgson JM, Lauer MS, Miller JM, Morin RL, Mukherjee D, Poon M, Rubin GD, Schwartz RS; American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Expert Consensus Documents. ACCF/ACR/AHA/NASCI/SAIP/SCAI/SCCT 2010 expert consensus document on coronary computed tomographic angiography: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Expert Consensus Documents. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;76 :E1-42.

A cooperative document of Cardiology and Radiology US Societies to define competency in non-invasive coronary imaging with MSCT]. Obviously the technical aspects cannot cancel the need of a sufficient background clinical knowledge to pose correct indications, interpret the non invasive imaging tests, maintain an appropriate follow-up.

STRUCTURAL HEART DISEASE

TAVI and new mitral interventions (edge-to-edge leaflet clipping, direct or indirect annuloplasty, etc) are the main focus of attention but also novel tricuspid interventions, PFO and ASD closure, LAA appendage closure etc require a consistent pattern of training. To some extent and especially for the newest interventions, operator training is as important as appropriate indications and planning in delivering optimal results. Training is a challenge also for experienced interventionalists because it requires advanced knowledge of valve pathology, the biological surgical prostheses (valve-in-valve is probably the indication with greatest consensus), non-invasive imaging with special focus on MSCT and transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography. Functional mitral regurgitation or LAA closure require specific knowledge of heart failure and electrophysiology.In most cases training is directly provided by the companies selling the specific devices involved. In principle this method is not desirable because it creates insurmountable bias in the proctors who are unlikely to provide balanced information on indications, advantages and risks of the device in question. While many companies must be congratulated on the quality of the didactic courses they organise, both the completeness and scientific reliability of other theoretical courses is questionable. Patient safety when a proctor is called to operate in an unfamiliar environment with limited previous interaction with the local team may also represent an issue. Despite these theoretical pitfalls, results of proctored TAVI cases have been shown to come close to the best results of experienced centres, possibly because the most straightforward indications are selected or alternatively thanks to the relative technical simplicity of these procedures. The involvement of interventional societies and a more independent and better regulated training process, especially for the most complex procedures, should be addressed rapidly when future procedures develop.

The long-term challenge is much greater, we must train new “hybrid” specialists with mixed surgical and interventional skills who will be ideally placed to perform and develop the growing number of mini-invasive procedures due to replace more invasive conventional surgical approaches. This requires an enormous change in mentality from both cardiologists and cardiac surgeons resulting in innovative curricula for future specialists. Interventionists, already a new breed with a mixed background, are in an ideal position to lead this change [1616. Di Mario, C. Interventional cardiologists: a new breed. EuroIntervention. 2009;5:535-37. ].

RADIATION PROTECTION

Knowledge of the basic principles of radiation physics and radioprotection is an essential prerequisite for the use of ionising radiation in all European countries. The training and revalidation courses, however, should go beyond the basic principles, which are common to other medical operators from dentists to orthopedic surgeons. Practical tips and tricks to avoid or reduce the radiation burden to the patient and the operator must be taught in order to ensure they make use of the best x-ray systems/settings and the most advanced shielding modalities to reduce radiation exposure to patients and cathlab staff alike.

MULTIDETECTOR COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY

In the United States, the Society of Coronary Angiography and Interventions in conjunction with the American College of Cardiology Foundation and the American Heart Association, the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, the American College of Radiologists, the Society of Atherosclerosis Imaging and Prevention and the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography have promoted the preparation of a consensus document [1717. Mark DB, Berman DS, Budoff MJ, Carr JJ, Gerber TC, Hecht HS, Hlatky MA, Hodgson JM, Lauer MS, Miller JM, Morin RL, Mukherjee D, Poon M, Rubin GD, Schwartz RS; American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Expert Consensus Documents. ACCF/ACR/AHA/NASCI/SAIP/SCAI/SCCT 2010 expert consensus document on coronary computed tomographic angiography: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Expert Consensus Documents. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;76 :E1-42.

A cooperative document of Cardiology and Radiology US Societies to define competency in non-invasive coronary imaging with MSCT] to define standards for training, accepting the principle that no medical professionals may have all the background needed for the interpretation. Cardiology fellows are expected to have comprehensive exposure to both acquisition and interpretation of cardiac MSCT throughout their training, and should master the relationship between the results of the MSCT examination and findings of other cardiovascular tests, such as catheter based selective angiography, nuclear cardiology, cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging and echocardiography (when appropriate). To go one step further and be able to interpret and reconstruct coronary and cardiovascular investigations, the minimum number of cases to be performed and interpreted under supervision and the duration of training have already been indicated. Three different levels of expertise are defined ( Table 1 ) and it is suggested that all cardiology fellows, most practicing cardiologists and especially interventional cardiologists should attain at least the first level of training. Although this level does not qualify a doctor to perform and interpret cardiac MSCT independently, it entails understanding the basic principles, indications, applications and technical limitations of MSCT and the interrelation with other diagnostic tests, which are essential for the appropriate use of cardiovascular MSCT in clinical practice. Professionals however, may receive training in their practice settings. Indeed there are a number of ways in which physicians can validate expertise and competence in MSCT.

CBCCT (cardiac computed tomography certificate of advanced proficiency) candidates are given multiple-choice electronic tests to be completed on a PC covering clinical indications and limitations of MSCT, scan technique and post-processing, principles of x-ray radiation physics and radiation protection. Although comprehensive in terms of background knowledge, these tests do not evaluate some practical abilities involved in cardiovascular MSCT such as patient preparation and instruction, choice of the most appropriate scan technique, optimisation of contrast injection protocol and scan parameters, manipulation of the three-dimensional MSCT dataset on a workstation to judge the reliability of the data, and importantly the reporting of the study. For these reasons, when possible, workplace-based assessment may reflect better the trainees’ acquired competence.

The European Society of Cardiology WG on Nuclear Cardiology and CT encourages the accreditation with the CBCCT. This reflects the relative paucity of training schemes across Europe offering comprehensive multimodality training in cardiac imaging (including cardiac MSCT). Trainees therefore, have to look for training at different facilities when the primary programme cannot fully accommodate their needs. The European Society of Radiology has identified cardiovascular multimodality cross-sectional imaging as a subspecialty and has made available a number of training and exchange fellowships to overcome the existing limitations and disparities in the availability of multimodality cardiovascular imaging facilities across Europe. Some national societies, for instance the British Society of Cardiovascular Imaging which has members with different backgrounds (but mainly in radiology and cardiology), have endorsed training guidelines similar to those published in the United States and also offers opportunities for curriculum-based accreditation. In Great Britain, applicants for level 2 accreditation in cardiac CT must have attended a dedicated level 2 course for a minimum of 5 days supplemented by onsite training at a hospital where one had reported at least 150 contrast cardiac CT examinations under the supervision of a grade 3 certified trainer. The case mix must include at least 50 cases of coronary analysis with the presence of significant stenoses, 25 cases of non-coronary pathology, 25 cases of patients who have undergone CABG, and at least 10 cases of patients with coronary stents.

INVASIVE INTRACORONARY IMAGING AND NON-IMAGING TECHNIQUES

Fractional flow reserve is the accepted standard proposed in the new ESC Revascularisation Guidelines [1818. 2014 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization: the Task Force on Myocardial Revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Developed with the special contribution of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI). Kolh P, Windecker S, Alfonso F, Collet JP, Cremer J, Falk V, Filippatos G, Hamm C, Head SJ, Jüni P, Kappetein AP, Kastrati A, Knuuti J, Landmesser U, Laufer G, Neumann FJ, Richter DJ, Schauerte P, Sousa Uva M, Stefanini GG, Taggart DP, Torracca L, Valgimigli M, Wijns W, Witkowski A; European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines, Zamorano JL, Achenbach S, Baumgartner H, Bax JJ, Bueno H, Dean V, Deaton C, Erol Ç, Fagard R, Ferrari R, Hasdai D, Hoes AW, Kirchhof P, Knuuti J, Kolh P, Lancellotti P, Linhart A, Nihoyannopoulos P, Piepoli MF, Ponikowski P, Sirnes PA, Tamargo JL, Tendera M, Torbicki A, Wijns W, Windecker S; EACTS Clinical Guidelines Committee, Sousa Uva M, Achenbach S, Pepper J, Anyanwu A, Badimon L, Bauersachs J, Baumbach A, Beygui F, Bonaros N, De Carlo M, Deaton C, Dobrev D, Dunning J, Eeckhout E, Gielen S, Hasdai D, Kirchhof P, Luckraz H, Mahrholdt H, Montalescot G, Paparella D, Rastan A, Sanmartin M, Sergeant P, Silber S, Tamargo J, ten Berg J, Thiele H, van Geuns RJ, Wagner HO, Wassmann S, Wendler O, Zamorano JL; Task Force on Myocardial Revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery; European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2014;46:517-92.

In the latest European guidelines on Myocardial Revascularisation developed in cooperation between European Society of Cardiology and European Association of Cardiothoracic Surgery specific definitions of number of procedures to maintain operators’ competency are not addressed, reflecting the variety of training and revalidation processes in the various European countries], in the absence of non-invasive evidence of ischaemia, for the evaluation of stenoses of angiographically “intermediate” severity. The simplicity of the technique is one of the key elements of its success but nevertheless pitfalls must be addressed in specific seminars and learned from practice. There is consensus among experienced interventionists that a background experience of IVUS is an eye opener in terms of confidence in the application of appropriate balloon diameter and pressure and selection of techniques of lesion preparation. OCT has the advantage of a crisp delineation of the lumen-wall interface which allows reliable automated measurements of lumen area. For both techniques, specific training is required in order to consistently acquire and properly interpret the images and extract the relevant clinical information in the midst of a complex angioplasty procedure [1919. Prati F, Guagliumi G, Mintz GS, Costa M, Regar E, Akasaka T, Barlis P, Tearney GJ, Jang IK, Arbustini E, Bezerra HG, Ozaki Y, Bruining N, Dudek D, Radu M, Erglis A, Motreff P, Alfonso F, Toutouzas K, Gonzalo N, Tamburino C, Adriaenssens T, Pinto F, Serruys PW, Di Mario C. Expert review document part 2: methodology, terminology and clinical applications of optical coherence tomography for the assessment of interventional procedures.; Expert’s OCT Review Document. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2513-20. , 2020. Prati F, Regar E, Mintz GS, Arbustini E, Di Mario C, Jang IK, Akasaka T, Costa M, Guagliumi G, Grube E, Ozaki Y, Pinto F, Serruys PW Expert review document on methodology, terminology, and clinical applications of optical coherence tomography: physical principles, methodology of image acquisition, and clinical application for assessment of coronary arteries and atherosclerosis. Expert’s OCT. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:401-15. ]. Training programs must include all the techniques included in the Recommendations because it is very difficult to recreate the breadth and intensity of a training fellowship once a physician has assumed full-time clinical responsibilities.

CHRONIC TOTAL OCCLUSIONS

The EuroCTO Club has developed a model of training for defining lesions of low complexity, accessible with conventional PCI material and small changes in the conventional technique (i.e., bilateral injection, tapered soft polymer coated wires) and progressively more complex lesions that should not be approached without adequate training and/or the presence of a proctor.[2121. Di Mario C, Werner GS, Sianos G, Galassi AR, Büttner J, Dudek D, Chevalier B, Lefevre T, Schofer J, Koolen J, Sievert H, Reimers B, Fajadet J, Colombo A, Gershlick A, Serruys PW, Reifart N. European perspective in the recanalisation of Chronic Total Occlusions (CTO): consensus document from the EuroCTO Club. EuroIntervention. 2007;3:30-43.

This white paper of the European Club on Chronic Total Occlusions recommends a specific training path for operators willing to address this complex technical challenge, 2222. Di Mario C. Ars longa, vita brevis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2:487-8. ]

Conclusions

Interventional cardiovascular practice remains a dynamic, rapidly evolving sub-specialty of cardiology which requires an optimal system for structured training. Appropriate legislation should be issued reflecting the growth of cardiology subspecialties and the need of certified training, following the US model. Despite the absence of a recognized training pattern, Europe remains an acknowledged leader in education and training in interventional cardiology thanks to the success of European courses and educational activities. Multiple ongoing initiatives have been promoted by EAPCI and the National Interventional Societies to fill the gap created by the lack of a formal homogeneous training and certification process and provide the conditions for a successful expansion of interventional cardiology in peripheral and structural interventions [2323. Di Mario C, Roffi M Peripheral interventions: how long will they remain a missed opportunity?. EuroIntervention. 2011;7:177-81.

Cardiologist expert in peripheral interventions try to explain the challenges facing the growth of cardiology-led carotid, renal and lower limbs interventions in Europe, starting form the lack of a specific training path and agreement among the various players in the field, 2424. Di Mario C, Alfieri O, Iung B, Serruys PW. Transcatheter valves and interventional cardiology. EuroIntervention. 2011;6:673-7.

Considerations on training in transcatheter valve implantation issued in cooperation between the President/Past President of EAPCI, EACTS and the ESC WG on Valve Disease].

Personal perspective - Carlo DiMario

The official approval of a new specialty called Interventional Cardiology requires a direct decision by National Governments since this legislation is demanded by the European Union to individual countries. A change in this is very unlikely in the near future. However, the European Union is expected to check compatibility with the essential principle of free movement of workers, including professionals, within the member states. If key country members follow the EAPCI proposal by developing national subspecialty programmes modelled on the EAPCI curriculum, the EU might be induced to promote initiatives to grant legal recognition for this educational model. Whilst waiting for this long-term goal, the European interventional community should continue to deliver “unofficial” but well regulated and high quality programmes of interventional training and ensure that the appointment/accreditation of interventional specialists is limited to fellows who have undertaken an adequate training programme. A high quality offer of educational programmes in the main European congresses and the development of European fellows courses and initiatives for exchange of fellows can greatly facilitate this programme of integration and ensure the achievement of higher common standards of training.